Photo by Recycling Today staff.

Economic sanctions are far from a recent invention, with naval blockades having existed for nearly as long as have warships. Part of what blockades and sanctions reveal is the vital importance of raw materials in war and in peace.

In the run-up to World War II, as Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan invaded neighboring nations, the United States invoked sanctions before Pearl Harbor triggered formal declarations of war.

The withholding of oil was painful to all three Axis nations, but a halt in metal, minerals and scrap materials also played a role. In Germany, the need for nickel led to a Canada-based swindle that left a German buyer without the necessary metal. (This trade of what scrap dealers might call a “salted load” is the subject of a 2016 book called Hustling Hitler by Walter Shapiro.)

By the early 1940s, streetlights and lampposts in Tokyo and other large Japanese cities were being removed in an attempt to supply its raw materials-starved melt shops.

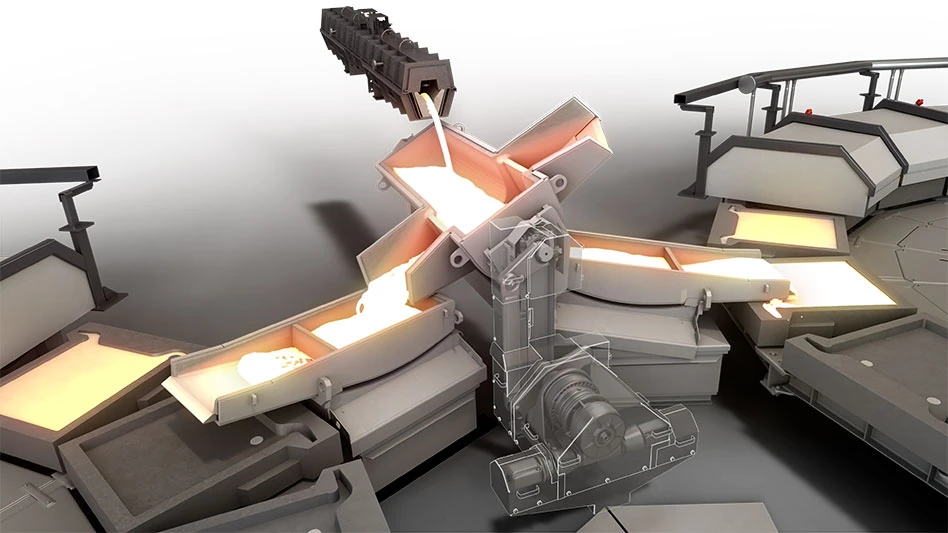

The 2020 book Mussolini’s War by British historian John Gooch provides a statistical portrayal of how Italy’s war production effort was vastly underperforming in part because of a lack of scrap metal. As Europe went to war in the autumn of 1939, Gooch writes that for the Italian steel industry, “Scrap iron [supplies] fell short by 42,000 tons a month” and that “partly as a result, monthly steel output fell in October by 50,000 tons to a total of 110,000 tons, which was 30,000 tons less than the minimum amount required.”

The underfed melt shops of Japan and Italy contrasted starkly with what would be labeled the arsenal of democracy ramping up in the U.S. In America, the iron range of Minnesota, copper mines in the U.S. West and generous supplies of domestic scrap materials saw its wartime production far surpass the estimates calculated by functionaries in Axis nation government bureaus.

The global response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is not poised to produce this sharp contrast. Russia is a net exporter of numerous raw materials (including oil and scrap metal), so the boomerang effect of the sanctions is all too real, especially in Europe.

For scrap recyclers, the ripple effects of sanctions made an immediate impact in the form of nickel, copper and aluminum price volatility. For several days, scale pricing and transaction pricing were clouded by uncertainty. (Again, especially in Europe, where metal is commonly traded on the London Metal Exchange.)

Beyond that, buyers of scrap metal, cardboard and plastic within the U.S. are unlikely to think of the sanctions on a daily basis as they collect and process materials.

Global traders, on the other hand, find themselves with a new list of considerations as they attempt to match materials with the best offshore market. In the financial press, the hunt seems already to have started to discover and unveil people and companies working around the sanctions.

The German news service Deutsch Welle (DW) posted an article in mid-March with the somewhat provocative headline “Swiss commodities traders help fill Putin's war coffers.” Through two world wars and the Cold War, Switzerland wore its neutrality like a badge of honor. Scrutiny such as that raised in the DW article indicates some of the luster may be fading from that badge in the minds of many.

The best outcome, nearly everyone can agree, is for a swift end to combat, leading to a phase where sanctions can be peeled back rather than continuing to accumulate. In the meantime, however, scrap commodity traders will be part of a global network poised to receive a great deal more attention than it does in more stable times.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Unifi launches Repreve with Ciclo technology

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta