m.malinika | stock.adobe.com

The European Union is leading the way with regulations designed to improve the environmental footprint of products and commerce in general. Two key aspects are reducing the carbon footprints of products to address climate change and the overall life cycle of materials through to ultimate end-of-life treatment. This last step is clearly of great importance to recycling companies. As part of the European Green Deal, the European Commission has created a Circular Economy Action Plan that will help enforce the closed loop of materials recycling in the region.

By contrast, the U.S. has turned away from such legislation, with the proposal for a Green New Deal not even being brought up for a vote. In the meanwhile, the EU has plans to promote and extend its action plan to broader regions.

The European Commission writes, “The Circular Economy Action Plan [CEAP] [f]or a cleaner and more competitive Europe stresses that the EU cannot deliver alone the ambition of the European Green Deal for a climate-neutral, resource-efficient and circular economy. The new CEAP thus confirms that the EU will continue to lead the way to a circular economy at the global level and use its influence, expertise and financial resources to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in the EU and beyond.”

I previously reported on the EU’s mandatory reporting of substances of very high concern under the Waste Framework Directive (See “What the EU’s waste framework directive means for electronics recyclers around the world.”). The Substances Contained in Products (SCIP) database is now in full operation.

Since the SCIP database is open to the public, recyclers in any location have free access to this information at https://echa.europa.eu/scip-database. Only substances listed under the EU’s REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) regulation need to be reported. While serving its intended purpose and containing millions of entries, unfortunately, the SCIP does not report the other contents of products that could include valuable and highly recyclable metals such as aluminum, steel, copper, silver or gold. It also lacks additional information about the product and its optimum end-of-life treatment.

The circular economy legislation would help enforce recycling of all kinds of goods, with a few to be implemented initially. And, as we all know, the circular life cycle concept just makes perfect sense as opposed to a linear flow of products ending up largely as waste. The circular economy concept now has new a regulatory face with more specific plans and requirements to bring new life to recycling. More than ever, the consumption phase would hand off to recycling rather than to landfill and/or incineration, completing the circular loop back to resources.

Passports required

The draft Proposal for Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation would require information about the product that travels with it throughout its life cycle until the item is ready for recycling—a kind of digital product passport (DPP).

Among other data, the DPP would include the presence of substances of concern and information to guide recycling. This is a full list as provided in the proposed EU Ecodesign regulation.

“Article 1 Subject matter and scope.

“1. This Regulation establishes a framework to improve the environmental sustainability of products and to ensure free movement in the internal market by setting ecodesign requirements that products shall fulfill to be placed on the market or put into service. Those ecodesign requirements, which shall be further elaborated by the Commission in delegated acts, relate to:

(a) product durability and reliability;

(b) product reusability;

(c) product upgradability, reparability, maintenance and refurbishment;

(d) the presence of substances of concern in products;

(e) product energy and resource efficiency;

(f) recycled content in products;

(g) product remanufacturing and recycling;

(h) products’ carbon and environmental footprints;

(i) products’ expected generation of waste materials.

“This Regulation also establishes a digital product passport (‘product passport’), provides for the setting of mandatory green public procurement criteria and creates a framework to prevent unsold consumer products from being destroyed.

“This Regulation shall apply to any physical good that is placed on the market or put into service, including components and intermediate products.”

Excluded are food and feed, living plants and animals and medicinal products.

Substances of concern, as well as recycling guidelines, are key areas where information directly linked to a complex product would be made available for access anywhere through digital technology.

How will this be done? While not yet completely certain, it appears that some kind of extension to already familiar computer-readable product codes could be used. One of the general approaches still being defined is how the data would be communicated across global computer networks based on some identification on the product itself. One of the players here is GS1, the standards group that has implemented numerous types of product bar codes and related identifiers.

There are many examples of familiar and successful product identifiers. The idea would be that information relevant to the circular economy would be retrieved easily by reading a similar code to be used not only by consumers but also by parties needing to know more about the contents and manufacturers’ instructions for recycling.The new DPP requirements would be effective sometime after 2024, with initial product categories including textiles, construction, industrial and electric vehicle batteries. One more category such as consumer electronics or packaging also would be included.

Batteries have a head start

With the electrification of vehicles and the growth of battery-powered consumer electronics already in full swing, it is not surprising that batteries were selected for early implementation of the DPP. As will be expected of other types of products with some variation, the data that would be made available in a battery DPP would include:

- source of materials;

- carbon footprint;

- recycled materials with percentages used;

- product durability;

- guidelines on repurposing or remanufacturing, if applicable, and, if not,

- guidelines on optimum material recycling.

Recycling of rechargeable batteries, of course, is already well-established in the EU member states through Eucobat, the European association of national collection schemes for batteries.

Collection and recycling support in the U.S. also has been available for two decades now through Rechargeable Battery Recycling Corp.’s Call2Recycle.

Although the focus here is on the EU and U.S., it seems likely that similar coverage will continue to extend to other regions in the coming years. It might be expected that the addition of DPP information could somewhat improve but not revolutionize existing battery recycling.

Packaging and plastics

It is less clear at this time how DPP information would improve this sector since the existing Society of the Plastics Industry, now the Plastics Industry Association, Nos. 1-7 codes have been in place for quite some time. Adding additional digital information on No. 6 polystyrene, for example, could hardly be expected to magically make it recyclable. The same goes for Misc. code No. 7. Even No. 1 polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, which is generally considered to be recyclable, might see little benefit from more digital data. Other types of regulations on plastic waste and collection targets would be of more benefit to the environment and improve feedstocks to specialty recyclers. Indeed, most such regulations focus on collection targets to avoid sending recyclable plastic, paper and metal packaging to landfills.

Ripple effects

The development and entry into force of DPPs would have direct impacts on companies in EU member states with ripple effects felt globally. While the detailed regulations have yet to be completed, the outlook is positive for recycling companies that would be able to freely access information about product contents and recycling guidelines. Where this will make sense for all types of products might become a question of value yet to be confirmed in practice. One might question whether the passport would improve upon the use of plastic packaging codes already in place. In general, though, the prospects to freely communicate information associated with products to effectively track and manage sustainability are positive.

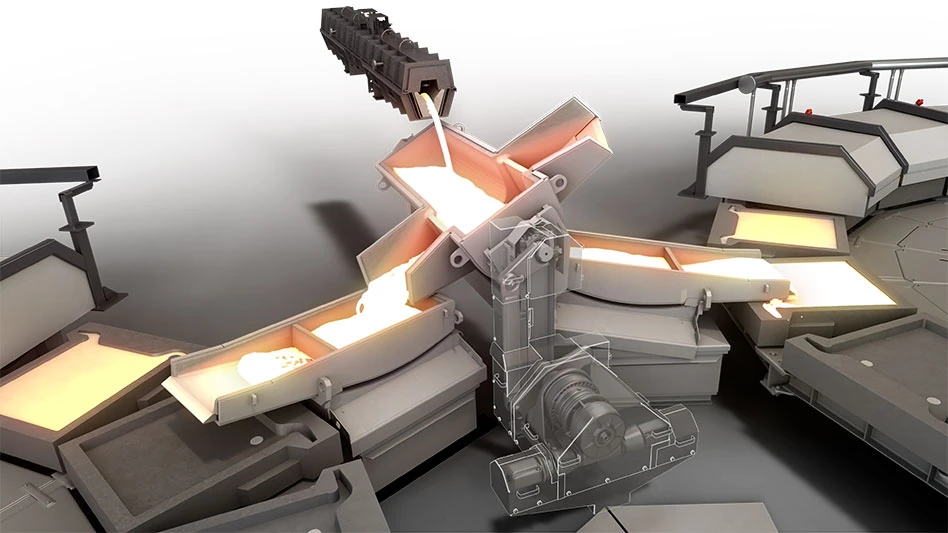

For electrical and electronic equipment, opportunities could arise to improve upon the ability to better handle substances of concern but also to gain visibility into valuable and recyclable metals that otherwise would be submitted to a less-optimum, generic shred-and-send-to-smelter scenario.

Much of the success of these passports will depend on original equipment manufacturers conducting life cycle assessments and conducting end-of-life models during the product design phase to optimize disassembly and sorting for circular recovery, then incorporating that information into the DPP.

Roger L. Franz is with TE Connectivity, a Swiss company that offers a broad range of connectivity and sensor solutions, proven in the harshest environments, that enable advancements in transportation, industrial applications, medical technology, energy, data communications and the home. He is based in the Greater Chicago area and can be contacted at roger.franz@te.com.

WANT MORE?

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta

- MTM Critical Metals secures supply agreement with Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations