© Milan Noga reco | stock.adobe.com

Recycling Today

archives

Tim Strelitz, co-founder and CEO of California Metal-X (CMX), describes himself as “curious” and a “problem solver” on his Twitter page (@tim_strelitz) and, when talking with Recycling Today, calls himself adaptable and unafraid to take risks. His career in metals recycling substantiates those self-assessments.

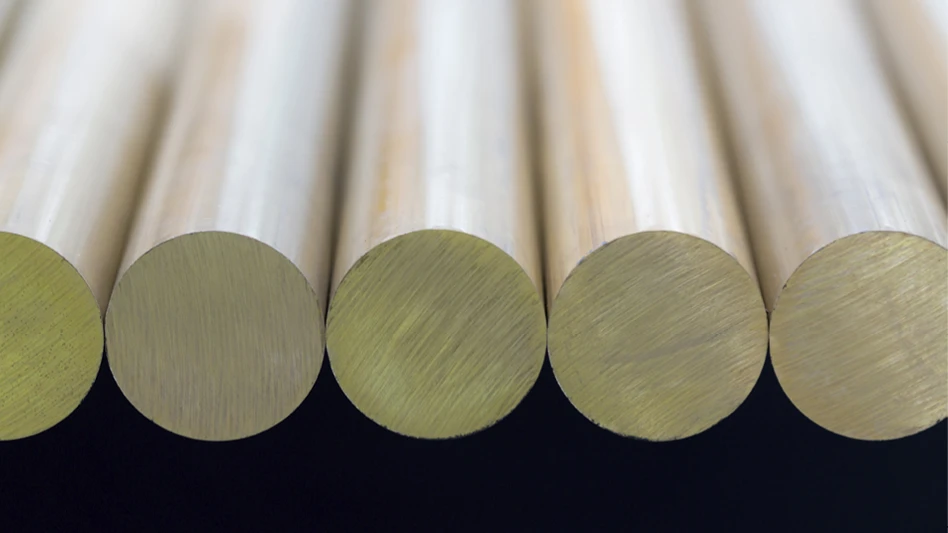

Strelitz and his wife, Karen, co-founded CMX in 1979 in Los Angeles. The manufacturer of engineered copper-based alloys for the foundry and mill industries has found success while similar businesses have shuttered in part because Strelitz says he’s learned to “float with the current” rather than swim against it.

“In the last 45 years, we’ve watched our industry collapse,” he says. “Our industry went from 80 to 90 manufacturers to just five today. I’m not the brightest bulb on the street. If I had been, we wouldn’t have stayed with this [business]. We’re tenacious, and we love combustion.”

His path to metals recycling

The metals recycling industry might seem like an unlikely career path for Strelitz, who has degrees in history and philosophy from the University of Denver. But he learned he had a strength for establishing process systems while working for family friend Joe Shapiro at National Metal and Steel, a ship dismantling company that was based on Terminal Island in California.

Strelitz first visited National Metal and Steel when he was 18. “I had never seen anything like it. You know, I grew up never even seeing a scrapyard,” he says of his New York upbringing.

At National Metal and Steel, he was confronted by a several-hundred-acre facility where destroyers, submarines and battleships were being dismantled. “I don’t know what happened that day, but I really liked what I was looking at,” Strelitz says.

After that visit, Shapiro invited Strelitz to join the company anytime he wanted, an offer Strelitz took him up on after graduating from college at age 21. “For the first two weeks, they had me as a laborer,” he says. “I was given a one-and-a-half horsepower braces saw, and these big, massive 20-foot-wide gantry cranes would drop a 40,000-pound superstone propeller from a destroyer.” He had to cut on each side of the prop, use the crane to flip it over and cut on both sides of the prop again so the propeller could be loaded into an overseas container destined for Japan.

While Strelitz says he didn’t like the task, “I wasn’t going to say a word because I knew something was going on.”

After about two weeks, his father called him to ask if he’d had enough of the job. Strelitz says he asked his father if he had told Shapiro to put him on that job to turn him off the industry. His father responded, “Well, not really. But he told me he was going to see whether or not you had the mettle to make it.”

Strelitz countered with: “Well, I’m here to tell you that I’m not done, and I like what I’m doing.”

He says of that time, “Very quickly, I realized I had a propensity for looking at equipment and process systems and I had an ability to simplify them and make them much more efficient.”

From there, Strelitz went to Pacific Smelting before buying Metal Briquetting, the company that would become CMX, from Harry Bergman for $10,000.

Embracing risk

When the Strelitzes purchased Metal Briquetting, the company pressed cast iron borings into pucks to sell to the iron foundries operating cupola furnaces in California. The company also warehoused bronze ingot for R. Lavin & Sons, headquartered in Chicago, for a rate of 1.5 cents per pound. The ingot warehousing accounted for nearly 70 percent of the company’s revenue at that time, Strelitz says, and took up nearly 40 percent of its time. Despite the revenue contribution, he made the decision to end the business arrangement with R. Lavin & Sons six months after buying Metal Briquetting.

“You only have so much energy and you only have so much time, and you need to be able to focus when you’re starting a business,” he says.

While his accountant at the time questioned the decision, Strelitz says it was a risk he was comfortable taking.

“I’m a big-time risk taker,” he says. “I’ve been very lucky in my life, and I want to think that you make your own luck, but I like risk. I like dark rooms. I like looking at things from every different point of view to understand them better.

“Risk, I can get my arms around. I can look at the mass and momentum. I can understand what I’m dealing with, and it always puts me in a place I’ve never been.”

The Strelitzes then focused on removing the brass from the cast iron the company was receiving. Doing so added roughly $10,000 per month to their income stream, Strelitz says. “So, then, we kept looking at it, and I realized all of the red borings that we were shipping back to Lavin … I could build a little rotary dryer, dry them out and use that same little press that we were running cast iron on and make red brass hockey pucks and ship them back.

“We became, I would I put it, kind of an amicus to the foundry customers we had,” Strelitz adds. “They really got a kick out of two young kids that could make things happen.

“The next thing I did is I invented a product called mechanical ingot. We could make semired brass, 81379, and red brass, 8535. Those two alloys were the biggest-selling alloys in North America at the time for the waterworks industry, and I was able to utilize my knowledge from my past jobs to take car radiators, shred them and reduce them, then add the necessary elements to bring them into specification. Then we would hydraulically press them. … All of a sudden, we were doing 4 and 5 million pounds a month, and that allowed us to put furnaces in.”

Perspective and adaptability

Strelitz says California-MetalX has survived and thrived through a constant effort to adapt and gain perspective.

“I get up around 4 in the morning, every morning; I don’t use alarm clocks,” he says. “I do that for several reasons. One is I usually get a good workout. Two, I always make breakfast for Karen and me. And, three, I have time to think when I get into the plant.”

Strelitz says once others arrive at work, “It’s over with. I’m now busy dealing with everything coming at me instead of me coming at things. People don’t get that, and the consequence of that is they take on more than they can handle and they become obstinate when they should be compliant.”

He adds, “People should know that the only time they should be swimming upstream is where they have a place that they know they can get to and it doesn’t drain them of their energy. Otherwise, the best thing I would recommend to everybody in business is to learn how to float with the current. Use the things around you to help you get to where you want to be. Don’t fight everything, just fight the battles you can win.”

In addition to being selective about the battles he takes on, Strelitz says he doesn’t listen when he’s told something cannot be done. His advice to other business owners and managers is: “Look at it for yourself and evaluate whether or not it can be done and whether or not it makes sense to do it.”

Removing lead from drinking water components was one such “impossibility.”

Strelitz says Richard Sykes, general manager with the East Bay Municipal Utility District in California, asked it if was possible to get lead out of drinking water components in 2006. When Strelitz said it was possible, he says Sykes said, “Well, Tim, everybody’s telling us it can’t be done. How would you do it?”

Strelitz responded by saying, “Don’t put lead in the product.”

CMX became the authorized licensed manufacturer of Eco Brass, which is also known as C87850 silicon alloy lead-free brass. Eco Brass was first made by Japan’s Mitsubishi in 2000.

“When I purchased the license for that alloy, I received phone calls from our competitors telling me it would never work, it wasn’t going to be allowed into the market,” Strelitz says. “Today, it’s about to take over bismuth alloys in a big way.”

In addition to adaptability and tenacity, he prioritizes getting varied perspectives from his team. While Strelitz says he is a “benign dictator,” he empowers the CMX team to challenge him. “It’s not about somebody being more right than somebody else. It’s [about] getting perspective.”

CMX is getting ready to adapt yet again, and Strelitz says the changes are “the sum total of everything we’ve learned over the last 45 years.”

While he’s not ready to talk about those changes, he says, “We have not stopped innovating. And, if anything, we’re doing more now than we’ve ever done before in an area that is extremely exciting, and that’ll come out in the next 12 months.”

Strelitz continues, “The idea for us is always to make the best metal at the best price, and so that’s what we’re focused on right now.”

Explore the May 2023 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- BMW Group, Encory launch 'direct recycling’ of batteries

- Loom Carbon, RTI International partner to scale textile recycling technology

- Goodwill Industries of West Michigan, American Glass Mosaics partner to divert glass from landfill

- CARI forms federal advocacy partnership

- Monthly packaging papers shipments down in November

- STEEL Act aims to enhance trade enforcement to prevent dumping of steel in the US

- San Francisco schools introduce compostable lunch trays

- Aduro graduates from Shell GameChanger program