Super-Size Shredders Handle Autos in Short Order.

THEN:

End-of-life automobiles have long been a source of scrap metal, but the systematic way in which they are now handled did not develop in one smooth stride.

In the early and middle 20th Century, taking apart an automobile was perhaps more labor-intensive than building one, especially since scrap recyclers did not enjoy the personnel to deploy an assembly line.

Wrenches, hammers and cutting torches all played a part in the disassembly process. But as tends to happen, when innovative thinkers who own a business see a labor-intensive process, they try to find a better way.

Automated compression was one of the first answers to the auto recycling riddle. According to Sam Proler from one of Houston’s long-time scrap recycling families, Henry Ford and managers who reported to him were among the first to bale automobiles, baling them one at a time and then feeding them to a furnace at the company’s River Rouge steelmaking plant in the late 1940s.

With iron and steel making up a larger percentage of a vehicle’s weight then, a baled automobile could make an acceptable feedstock for an integrated furnace.

The No. 2 auto bundle—whole vehicles baled as integrated furnace charge—thus became a processed scrap grade throughout the 1950s. "Everything in that car got baled together—including plastics and glass," metallurgist Dr. Richard Burlingame recalled for a 2002 Recycling Today article. "In the 1950s, the total amount of nonmetallics and nonferrous metals was [at most] 15 percent in a typical body that had been stripped down," noted Burlingame, who worked for Cleveland-based Luria Brothers from 1961 to 1986.

"It’s hard to believe now that there was any market for these bundles, but there was much more iron and steel used in cars then," according to Burlingame.

But that was changing, and Burlingame was hired by Luria Brothers in 1961 to help that company develop a new processing technique that was beginning to take hold in other parts of the country.

NOW:

When Henry Ford was ready to give up on baling autos one-at-a-time at his steel mill, Sam Proler turned up at the River Rouge complex to bid on his baling machine.

After touring the mill, Proler bought the baling unit as well as an old slag-breaker that became an early version of a guillotine scrap shear.

While each of these machines helped Houston-based Proler Steel Corp. prepare scrap for its steel mill customers, the use of such machines to process auto hulks began running into problems in the mid-1950s.

"Most steel mills didn’t want them—they had too many contaminants like copper and rubber," Proler recalled for a 2007 Recycling Today article.

On a lengthy airplane flight—fueled by screwdrivers and a desire to find a better way—Proler says he began sketching on a napkin the idea of taking a hammermill-style crusher used by mining companies to use as a machine to shred automobiles into smaller pieces.

According to Proler, most of the people he talked to—including potential suppliers of such a machine—"kept telling me why it wouldn’t work."

But Proler persisted, and in 1956 and 1957 set about building a hammermill-style shredder at the Proler Steel Corp. facility in Houston that became the prototype for several other "Prolerizers" that the company would ultimately build in other parts of the nation.

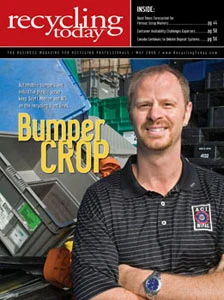

Also in Texas in the late 1950s, Alton Newell began making shredding plants that have since made his family’s last name familiar to buyers and users of metal shredding equipment. Alton’s son Scott Newell and grandson Alton Scott Newell III continue to design and build shredders as principals of The Shredder Co., Canutillo, Texas.

It is among several companies that now make shredders that process not only automobiles, but larger vehicles such as vans and light trucks.

The contamination issue has been addressed head-on not only to meet steel industry specifications, but so shredder operators can obtain increasingly cleaner grades of nonferrous scrap products using downstream systems.

Explore the May 2008 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Eagle Dumpster Rental identifies its MRF-unfriendly items

- American Securities acquires Integrated Global Services Inc.

- Fleetio integrates Maintenance Shop Network add-in

- 3rd Eye expands suite of fleet safety solutions

- Newsom orders SB 54 revision

- Biffa sees recycling, composting opportunities at events

- Copper market navigation stress lingers

- IWS ramps up NJ MRF