For a company that was founded in the 1800s, Ecore International prides itself on innovation and evolution in the rubber and tire recycling industry and continues to help set the pace for more sustainable manufacturing.

Originally founded in 1871 as Dodge Cork, a business that imported and processed cork from Europe, Ecore bills itself as a rubber circularity company rather than simply a rubber recycler.

Ecore’s product offering includes about 1,500 SKUs, including products for the surfacing, commercial flooring, sports and recreation flooring, health care, retail, hospitality and agriculture industries.

“We cover just about every vertical market within surfacing, both indoor and outdoor,” Ecore President and CEO Art Dodge says. “We don’t just provide finished product, we also provide the raw material. So, if you’re an outdoor sports contractor, we’ll provide granules, … we’ll provide components to contractors. It’s a core part of the business.”

The company formed a joint venture with Armstrong World Industries in the 1920s, with both companies establishing headquarters in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and, by 1930, became the first to develop the production of composition cork.

The company took the Ecore name in 2008 and now has 13 facilities across the United States. Three sites are dedicated to its Outdoor Surfacing business, seven house its manufacturing operations and the balance is comprised of either administrative offices or sites that reclaim and process recycled rubber or sort tires.

Dodge says Ecore focuses much of its efforts on truck tire recycling and, last year, the company processed approximately 4.35 million truck tire equivalents— 20 percent of which is steel the company then sells to steel mills. He notes that Ecore has a variety of sourcing relationships throughout the industry, with the retreading industry being one of the most prominent. The company works with fleet operators that manage large numbers of trucks and trailers, collecting their used tires, grading them for reuse or recycling and channeling them into relevant markets, optimizing the use of the tire or its parts for the highest value.

“The process continues from there,” Dodge says. “In full circularity, the best thing you can do with a tire is to keep it going, so a truck tire, if it’s not damaged, can be valuable casing.”

The company also takes end-of-life tires that cannot be salvaged or reused, removing the steel and manufacturing rubber granules, rubber buffings or other feedstocks of different sizes for use in many manufacturing processes.

As trailers come into an Ecore facility, they’re unloaded with front-end loaders that remove bulk tires, but grading them is a manual process. After being graded, the tires are shredded using equipment supplied by Middlebury, Indiana-based Jomar Machining & Fabricating and Sarasota, Florida-based CM Shredders.

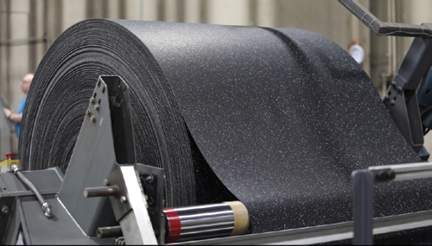

Once the tires are shredded, Ecore employs a variety of processing procedures using a Jomar Raptor and a CM Liberator to separate the metal from the rubber before further reducing the rubber granules through its milling operations.

“It’s like triple-distilled rubber,” Dodge says. “We clean it, clean it and clean it again so it gets to be 100 percent pure because we look at rubber as an incredibly valuable resource, and getting it back and refining it to the equivalent of a virgin state so it can be interchanged with virgin rubber is one of the core competencies we brought to the industry.”

A culture of innovation

Ecore also recycles shoe soles, tennis balls and any elastomeric material, and Dodge says the company has demonstrated to customers across the value chain the many possibilities of rubber recycling.

For example, in the early 1990s, Nike approached Ecore looking for a solution for its scrap shoes, and the two companies worked side by side to create the Nike Grind program.

The program involves collecting manufacturing scrap, unused manufacturing materials and end-of-life footwear, including rubber, foam, fiber, leather and textiles, separating the material and reusing or processing it into new Nike Grind materials that are then used in Nike products, retail spaces and workplaces, such as the Nike headquarters in Beaverton, Oregon.

“It’s really what keeps me motivated is how much fun it is to continue to invent something new,” Dodge says.

“The partnership we had with Nike taught us a lot. It began the process of thinking holistically about enabling customers to offer the promise of full circularity. … It set the platform for some of the continued evolution and growth that we’ve experienced and how to do it well.”

That growth has required technology and process innovation. Today, for example, Ecore upcycles recovered rubber into high-performance sports surfacing, a process Dodge says required technology that didn’t previously exist.

“Process innovation, material science innovation—all that innovative work and all that investment is part of what allows you to recapture value in reclaimed materials,” he says.

Ecore also has worked to develop processes to identify and track tires as they’re collected, as well as material science innovations that attempt to create elastomer alloys—a process Dodge says creates new families of materials that are unique to recycled rubber and that cannot be replicated with virgin material.

“That opens up the field of science for alloying rubber and plastic,” he says. “We’re looking at new science and technology to cross-link rubber and plastic to create new families of materials with new applications. That field of material science is one area of innovation we spend a lot of time in—how do you take materials and process them and create value by combining them?

“We have unique lamination technology where we can take a rubber substrate and laminate it to a different facial. … That adds a lot of value because it takes a lot of risk out. The application of those materials in the field can be risky. We derisk it for contractors by doing that in-house and delivering a finished system to the jobsite. That’s all technology we developed in-house and is part of the innovation culture within the company.”

Ecore also processes EPDM, or ethylene propylene diene monomer, rubber, recycling some 40 million pounds last year.

Circularity beyond recycling

Ecore takes a different approach to recycling, and Dodge even calls recycling “so yesterday,” at least in the rubber sector.

“Circularity involves reclaiming material and remaking the same product without generating waste over and over again,” he says. “Circularity isn’t possible at this time because rubber from used tires can’t be used to make new tires. So, recycling rubber [back into tires] is very difficult—almost impossible.”

Some in the industry are reducing rubber back into carbon black and trying to incorporate that into tires, however, Dodge says, what sets Ecore apart is that it not only “upcycles” tires into performance flooring and surfacing, but it goes a step further by reclaiming that material at the end of its useful life and converting it back into the same products.

“In doing so, we avoid the eventual landfilling of rubber,” he says. “Everybody else is landfilling rubber from tires after one additional use, but we are striving to keep it out of landfill forever. That’s why we ask, ‘What if all the rubber the world needs has already been made?’

“We are constantly evaluating opportunities to reclaim value before disposing of material. So, we look at our business as having multiple dimensions of what we can do to harvest value with the materials we’re able to bring back to life. We also look at recycling [materials] back into other beneficial reuses, so taking tire rubber and making running tracks [and] sports surfaces and transitioning it into a new market.”

Dodge also notes the benefits of “downcycling,” or recycling material into a lower-value but still beneficial use.

“[Those all are] opportunities to reclaim value before you have to dispose of [the material],” he says.

“You have to move that material through your system on a regular, reliable basis, and so for whatever fraction of material you have to redeploy into a higher beneficial use, you’ve got to find a place for the rest of it.”

To find a place for that material, Dodge says Ecore has to be in all markets at the same time to ensure 100 percent of the volume it brings in also can go out—something he calls “mass balance.”

“We’re balancing the inbound and outbound material flow on a regular basis and building the infrastructure to do that reliably and create a circular model where you can also reclaim products we manufacture at the end of life,” he says. “It requires a very sophisticated logistics system in terms of pickup and delivery.”

That balance has become part of Ecore’s DNA, and establishing what Dodge says is a new business paradigm is something that differentiates the company from the rest of the industry.

“We have a fully integrated circularity platform that allows us to go from reclaiming waste to redeploying it into a finished product, reclaiming that finished product and doing it again,” he says. “That means you’ve got to control the entire value chain. Building out that value chain has obviously taken a lot of time and a lot of work by a lot of people.”

Business relationships both within and outside of Ecore are crucial to this work, and Dodge says flexibility is a key part of the company’s success.

“There are just hundreds of relationships and conversations that have to be had,” he says. “Everybody wants to on-ramp and off-ramp onto the model at a different place, and you can’t tell customers how to do business. You need to do business the way they want to do it, which means you’ve got to be highly flexible and very nimble—allowing your model to allow people on and in and out whenever and however they want. ... That’s one of the core strengths of Ecore.”

That strength requires “nonstop, ongoing” work to maintain, with Dodge equating the process to “building the plane while we’re flying it.”

To stand behind its circularity claims and further advance its mission, Ecore hired Chief Circularity Officer Shweta Srikanth in May 2024.

The role was created to spearhead the company’s commitment to sustainability and circular economic practices while driving strategies to reduce environmental impact and enhance overall sustainability within Ecore’s operations.

Part of that involves overseeing Ecore’s TRUcircularity program, which creates a legally binding guarantee to its customer that Ecore is responsible for the end-of-life of material it collects. A TRUcircularity agreement is a product commitment stating that if an entity wants to offload material and not be responsible for its disposal, Ecore then will take full responsibility for collecting and processing that material at end of life.

For example, if Ecore is installing surfacing for a school playground, it will enter into an agreement with the school district that says at the end of the surface’s useful life, so long as that entity is still working with Ecore, the company will own the responsibility of collecting the material for reuse or recycling. In other words, Dodge says, it’s a “no burn, no landfill guarantee,” and Ecore will provide a chain of custody report to prove it.

It’s an ever-evolving program—part of the “building the plane while flying it” approach, and Dodge says it has to account for questions like when does a full circularity guarantee make sense? When can the company actually deliver on the promise that it’s going to build out those capabilities and make them stronger? How does it solve for moving material across its network?

“We believe circularity, once we’ve demonstrated we can do it, will continue to grow and expand, and that’s one of the major drivers for the continued growth of the business,” Dodge says, adding that once Ecore demonstrates the chain of custody of collected material, it can show customers where it’s going and how it’s being used.

“You then have very dedicated resources to tracking and tracing volumes throughout the network, and it’s self-perpetuating,” he says. “You can continue to track those volumes through our network and show customers where those materials have been redeployed and be able to do it over and over again. That’s the magic of rubber.”

Making magic from rubber

Dodge refers to the rubber recycling process and Ecore International’s role in it as “making magic.”

“Nobody’s an employee, everyone’s a magician because we take things nobody wants, and we turn them into things people pay a premium for,” he says.

“Everything we do is magic … solving customers’ problems in real time and demonstrating that we can do it. We’re partnering with people all across the ecosystem … that want a solution. … Building out a fully integrated ecosystem was ultimately the motivation to putting circularity at the forefront of our business.”

He emphasizes the problem-solving aspect of the business, too, which goes back to the question, “What if all the rubber the world needs has already been made?”

At Ecore International, it’s about showing that recycled rubber is as good, if not better, than virgin material and proving it on a global scale.

“I think we’re helping the world transition from a linear economy to a circular economy,” Dodge says. “There’s been a lot of conversation, a lot of books written about it, but very few examples of companies that have actually done it.

“Ecore truly is a unique entity in the way we go to market, the way we’ve designed our business model, the way our ecosystem works and how we are allowing ourselves to enter into other industry ecosystems. We’re really trying to solve problems by bringing to market a fully integrated, circular platform that allows people to solve their own problems.”

Explore the March 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- ReMA opposes European efforts seeking export restrictions for recyclables

- Fresh Perspective: Raj Bagaria

- Saica announces plans for second US site

- Update: Novelis produces first aluminum coil made fully from recycled end-of-life automotive scrap

- Aimplas doubles online course offerings

- Radius to be acquired by Toyota subsidiary

- Algoma EAF to start in April

- Erema sees strong demand for high-volume PET systems