Recent years have been prosperous ones for many metals recyclers, resulting in the kind of market that has given many companies the confidence to boost their plant and equipment line items and capital investments.

Among those for whom such investments are among the most considerable are operators of auto shredding plants. The shredding plants themselves can require significant maintenance and periodic upgrading, while the downstream systems can entail an additional level of attention.

When it comes to configuring downstream portions of auto shredding plants, the key recently has been automated sorting and separating.

MAGNETIC ATTRACTION. The power of magnets to attract ferrous metal remains a vital first step in sorting and separating at shredding plants in particular.

Although most new magnetic products and technologies involve advances in identifying and separating the nonferrous portion of the shredded stream, pulling out the ferrous shred remains critical.

Drum magnets and suspended magnets have been employed in this task since auto shredders were first designed and installed, and the casual observer may not notice whether much has changed in this area.

But Don Morgan, a product manager based in the Milwaukee office of Walker Magnetics, remarks that there have been advances and changes in preference in these workhorses over the decades.

Permanent magnets and electro-magnets vie for market share in this segment, with recent advances in permanent magnets allowing them to provide agitation of material that can help improve performance.

"Theoretically, the field strength is very similar" between the two types of magnets, says Morgan, who also notes that purchasers may favor one style over the other for different reasons.

"An advantage of electro-magnets is that you can shut them off," he comments. "With permanent magnets always being on, that can entail some maintenance problems."

Permanent magnets, however, conserve power relative to the their electro-magnetic counterparts. The amount of power saved, in the scheme of entire shredding plant, is probably "peanuts" Morgan also notes.

The advent of rare earth materials in the 1980s helped lend added strength to some magnets, Morgan also notes. "A number of years ago, permanent magnets had to be within 10 or 12 inches of the conveyor, but the new rare earth ones can be suspended up to 15 inches away and still equate with an electro-magnet," he remarks.

| Sorting or Separating? |

|

Is a magnetic separator a sorter? Sort of! Magnetic sorting consists of using the power and influence of magnetic devices to sort ferrous products from non-magnetic debris. Magnetic separators, whether magnetic pulleys, suspended magnets or magnetic drums that are placed appropriately in a system can remove or sort these ferrous materials from those that are non-magnetic. Now what about the valued metallics that cannot be recovered magnetically? Certainly you can hand sort. You can also size the material to sort out oversize from fines. You can classify material by specific gravity, but you could also use an eddy current unit that sorts by conductivity and particle density. Thomas Edison, who had the first patent on an eddy current device in 1889, did not have rare earth permanent magnet material available during his lifetime, nor were there aluminum cans to recover. Magnets can sort nonferrous metals, classifying the conductive material such as aluminum, copper, stainless steel, etc., using a rotor of alternating poles, like a motor. Furthermore, all metal separators can sort even smaller particles missed by eddy currents by using inductive detection methods. --Don Morgan, product manager/magnetic separation specialist, Walker Magnetics, Milwaukee |

The drum magnet remains the "bulk worker" at many shredding plants, says Morgan, while suspended cross-belt magnets often pick up remaining ferrous material later in the process.

One variation on the traditional ferrous magnet is a stainless steel separator offered by SGM Magnetics. It pulls out and sends iron and carbon steel material onto one path and also pulls out slightly magnetic stainless steel fragments and, via a splitter, sends them into another stream.

Analyzing what has been shredded for its nonferrous content is a task being addressed by bulk scrap analyzers offered by companies such as Gamma-Tech LLC or Austin AI.

Jim Schwartz of Metso-Texas Shredder’s San Antonio office notes that Metal Management Inc., PSC Metals and the River Metals Recycling subsidiary of David J. Joseph are among the recyclers using the machines to determine which portions of their shredded streams are suitable to upgrade as low-copper shipments. "It clearly addresses the trend of steel mills wanting to know their copper levels before they melt," says Schwartz.

POLAR OPPOSITES. While traditional magnets attract the iron-bearing portion, magnetic technology of different sorts address the nonferrous metals stream at shredder plants.

Eddy current technology, which sends nonferrous metal flying away via magnetic repelling, is well established at shredder plants.

Increasingly, it is being supplemented by induction sorting machines offered by companies such as Steinert and SSE/Wendt Corp.

Effective induction sorting allows shredding plant operators to recover more nonferrous metals that even the best eddy current units might miss, including stainless steel fragments.

Testimonials from Steinert customers such as General Iron Industries in Chicago, posted on the company’s Web site, indicate that installing one of the machines can quickly pay off. General Iron’s Adam Labkon remarks, "Since installing our 80-inch [induction sorting system], we are recovering about five tons of nonferrous daily, most of which is stainless steel and some wire and other hard-to-get metal, such as breakage or balled-up nonferrous."

In addition to considering induction sorting units, shredder operators are now also being offered the chance to deploy an X-ray identification and separating technology that has been offered since 2004 by the German company SSE, represented in the United States by Wendt Corp.

According to Bill Close of Wendt Corp., the first X-tract unit has been on the job at a Camden Iron & Metal facility since early this year. The device uses X-ray detection to identify metals by atomic density and then uses a series of air jet nozzles to separate the materials after they are identified.

Close says the machine is best used on a high-metals concentrate stream, such as a post-shredder Zorba grade. "Of the input, approximately 70 percent might be aluminum, and what this machine allows you do to is separate and upgrade that to sell directly to the secondary consuming market," he notes. "The X-tract totally strips the zinc from the flow, and that zinc is a downgrade on that material."

The unit at Camden Iron "has been running for about one month, and what they are telling me is that they are easily getting into the secondary aluminum markets and close to getting to the primary markets," says Close. The device "can support up to 10 tons per hour of input," he notes, which can equal one large shredding plant served by four eddy currents.

Wendt is installing another X-tract machine at a Commercial Metals Co. shredder yard in South Carolina, and believes each installation will yield customer visits and additional sales.

Is there a next step after X-ray sorting? One possibility is optical sorting of the remaining non-aluminum "heavies," which can consist of copper, brass, zinc and loose coins. "Optical sorting is an option now, and I anticipate that it will become a popular option in the future," says Close.

Should global commodity prices remain aloft, attention to extraction and sorting will only increase.

DE-ZINCING. Separation technology is not found only at shredder yards, as one recent transaction in the scrap industry attests.

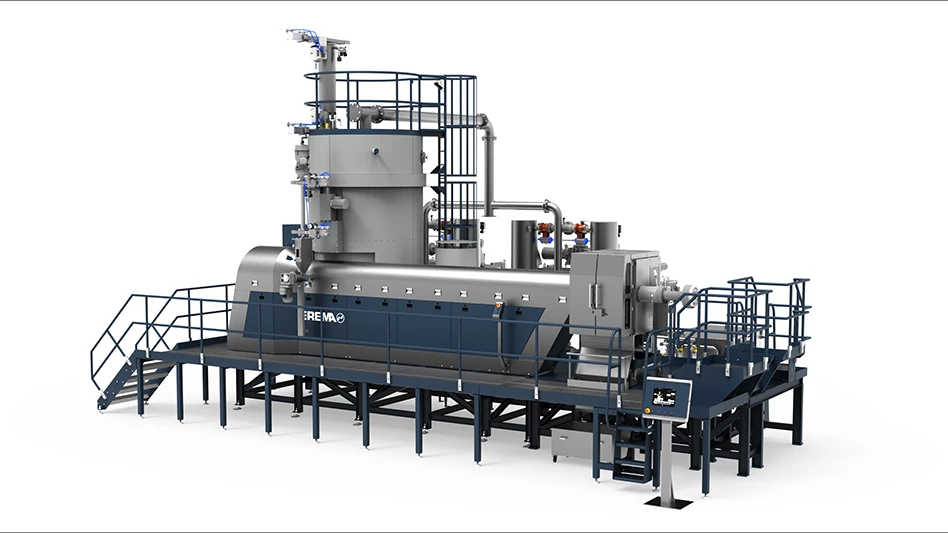

OmniSource Corp., Fort Wayne, Ind., and Meretec Corp., East Chicago, Ind., have entered into an exclusive agreement to commercialize Meretec’s de-zincing technology throughout the United States. Meretec holds an international patent for technology that removes and reclaims zinc from galvanized and zinc-coated ferrous scrap.

Reclaimed zinc is processed into a high-purity zinc powder, suitable for a specialty applications as well as typical commodity grade consumption. The process also returns a premium-grade shredded ferrous product, characterized by low-residual chemistries, improved density and higher yields than coated scrap, according to Meretec.

OmniSource will be responsible for sourcing raw materials and marketing the finished scrap products while Meretec will operate the patented processing facility in East Chicago and provide technical support. The companies will work jointly to develop on-site management programs that could include new processing plants for specific industrial generators, steel mills and iron foundries, according to a news release from OmniSource.

"We believe there is great potential for the application of the Meretec technology in metals recycling," says Danny Rifkin, OmniSource president.

Martin Young, Meretec chairman, says, "Meretec is convinced that combining our technology with OmniSource’s material sourcing and market expertise will help bring this revolutionary process to the U.S. metals recycling market in the most efficient way possible."

Meretec is a subsidiary of Metals Investment Trust Ltd., a U.K.-based holding company that is currently negotiating licenses for its de-zincing process worldwide. Its first formal licensing agreement with Southern Recycling in Australia was finalized in May of 2005, with agreements in Asia and Europe pending.

The Meretec plant in East Chicago was established in 2002 and was originally designed and equipped to handle up to 115,000 metric tons of scrap per year. At that time, Meretec managers estimated that the average ton of galvanized scrap should yield about 40 pounds of zinc flake product for outbound shipment.

Such investments in machines and even entire companies are an indicator of the measures scrap companies are taking to maximize the resale value of the many materials they handle.

The author is editor of Recycling Today and can be contacted at btaylor@gie.net.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the April 2006 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Green Cubes unveils forklift battery line

- Rebar association points to trade turmoil

- LumiCup offers single-use plastic alternative

- European project yields recycled-content ABS

- ICM to host colocated events in Shanghai

- Astera runs into NIMBY concerns in Colorado

- ReMA opposes European efforts seeking export restrictions for recyclables

- Fresh Perspective: Raj Bagaria