Just a few years ago, theft-minded scrap “collectors” were the scourge of an industry whose foremost problem was convincing police departments and legislators to pass anti-theft laws that would not overburden the scrap industry.

Copper pricing, at more than $2 per pound on trading exchanges, may still be high enough to tempt some criminals, but it is unlikely that $200-per-ton scrap iron prices are prompting schemes and capers among ethically challenged scrap collectors.

Throughout 2016, as in the year before, the bigger problem confronting scrap processors has been an overall lack of attention to scrap collection that has caused across-the-scale traffic in the ferrous sector to remain disappointing. November brought a boost in export demand and pricing for scrap, but overall in 2016 few positive signals of a rebound that might stimulate interest in the peddler community have been visible.

The doldrums

Ferrous scrap pricing can be considered to have a “precommodities boom” set of price ranges and a postboom definition. In between was the boom period starting roughly in 2004, when prices began to consistently average more than $200 per ton.

The peak—and end—of the boom is almost universally considered to be the spring and summer of 2008, when American Metal Market (AMM) composite pricing for No. 1 heavy melting steel (HMS) reached more than $500 per ton and prompt grades reached a peak of more than $800 per ton.

Before the 2004-2008 boom period, ferrous scrap most often checked in at closer to $100 (or below) per ton rather than at $200, and $300-per-ton scrap was essentially unheard of.

After the price plummet of October 2008, the “new normal” seems to have settled in within a range of from $200 to $400 per ton, depending on the grade and market conditions.

During the first three quarters of 2016, scrap recyclers experienced a few prices of below $200 per ton (in early 2016) but predominantly have been dealing with prices in the $200-to-$275 range.

A quirk in 2016 pricing has been the narrow spread of prompt grades pricing over shredded grades. This reached a peak, according to transaction pricing tracked by Pittsburgh-based MSA Inc.’s Raw Material Data Aggregation Service (RMDAS), in March and April, when mills (on average) actually paid more for shredded scrap than for prompt grades.

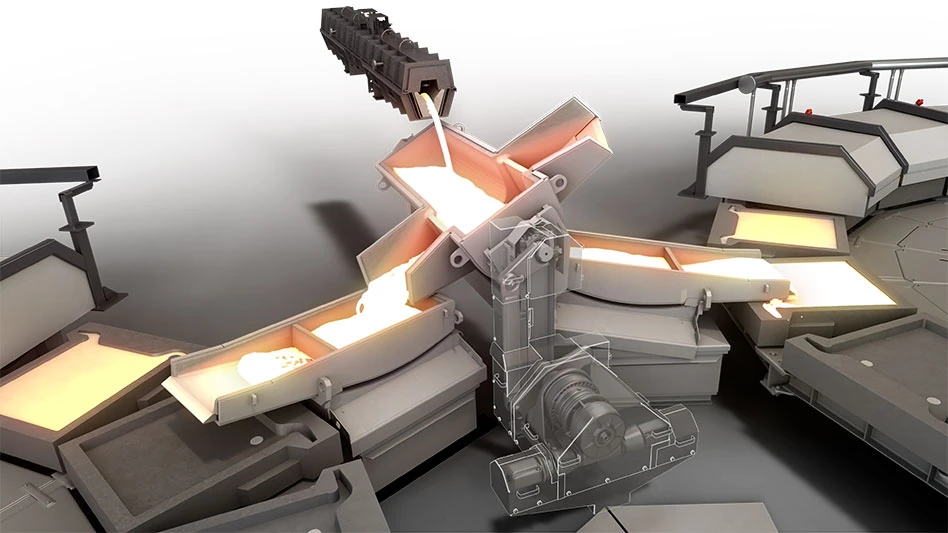

Recyclers attributed the flip-flop situation to more than one factor. Makers of auto shredders and downstream systems, as well as shredding plant operators, pointed to improvements in magnetic and other sorting techniques for providing shredded scrap with consistent chemistry. The improved shredded grade pricing, according to the narrative, rewarded the ongoing improvements made by the shredding sector to produce a vastly improved product compared with several years ago.

Those same shredding plant operators also acknowledged, however, that shredder plant feedstock brought in by collectors and peddlers was shrinking in volume along with pricing.

While automobile stamping plants and other factories that generate scrap were reliably yielding prompt grades in 2015 and 2016, the peddler community was getting smaller and smaller.

This situation was remarked upon early in 2016 (see the May Recycling Today article “Tough to Figure,” on pages 48-54) and did not improve much into the second and third quarters of the year.

About the kindest word scrap processors contacted throughout 2016 would say of their scrap flows was that they were “adequate” or “holding steady.” Other recyclers would refer to across-the-scale flows in some 2016 months being off some 20 percent from the previous year.

If warmer summer weather did not bring more peddlers into yards in the Northeast or Midwest, it seems clear that only increased scale prices will do the trick.

“With prices being lower and lower each month, the peddler traffic finally gives up,” says Greg Dixon, CEO of Nicholasville, Kentucky-based scrap brokerage Smart Recycling Management.

Too many collectors who might have been regular visitors to scrap yards from 2008 until as recently as 2014 might have determined “it is not worth it,” Dixon says.

If these peddlers did not harvest scrap in the spring and summer, Dixon says he believes that does not bode well for supply when the weather turns worse in parts of the U.S. “With winter coming, this will be an issue,” he predicts.

A big say in the matter

Despite the ability of some smaller scrap recyclers to retain their independence, a handful of North America’s largest scrap processing firms have accumulated considerable market share in certain regions.

Of particular concern to some recyclers, several of these companies are owned by electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmakers, who may not have the highest possible selling price as one of their priorities.

One multilocation scrap recycler that also produces steel is Irving, Texas-based Commercial Metals Co. (CMC). The firm started in 1915 with a single scrap yard before expanding into multiple locations and starting its EAF steelmaking business.

CMC, with its scrap recycling roots, has previously said it runs its scrap processing operations as a separate profit center and not as a preferential-price feedstock supplier to its mills. For a 1999 Recycling Today cover profile, then CMC Secondary Metals Processing Division President Harry Heinkele said of CMC’s mills, “They buy from us as they would any other steel mill. They have their own marketing team and do their own buying. They definitely buy more material from others than they do from us.”

Portland, Oregon-based Schnitzer Steel Industries is another recycler with EAF steelmaking capabilities. In a 2011 interview with Recycling Today, Schnitzer President and CEO Tamara Lundgren described a different approach that company takes.

“Our Steel Manufacturing Business (SMB) sources 100 percent of the scrap metal it uses through our MRB (Metal Recycling Business) to produce a wide range of products, including reinforcing bar (rebar), coiled rebar, wire rod, merchant bar and other specialty products,” she said. “While the mill pays competitive export pricing for its scrap, it benefits from availability and proximity to our MRB, and the close relationship between the businesses helps MRB to improve the size and purity of the products it provides both to SMB and customers globally.”

When it comes to ferrous scrap buying power, other major EAF steelmakers with scrap recycling divisions include Nucor Corp., Charlotte, North Carolina, which owns the David J. Joseph Co.; Brazil-based Gerdau, which owns scrap yards throughout North America; and Fort Wayne, Indiana-based Steel Dynamics Inc. (SDI), which owns OmniSource Corp.

Current and near-term future scrap pricing is a topic that must be approached carefully by recyclers, as anti-trust considerations are far-reaching.

Dixon, who moderated the ferrous scrap session at the 2016 ISRI (Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries) Commodities Roundtable in September in Chicago, says he brought this subject up at the event because he hears informally from many recyclers who are concerned about the extent of mill control of tonnage in the Midwest and South.

“My guess is that the publicly traded companies now own more than 50 percent of the volume and, yes, they influence pricing [used] by their yards,” he comments.

He asks whether the EAF mill companies that own their own yards, by “buying their material first and not buying from some [other] people, may have been able to keep a lid on prices?”

Dixon adds, “This has changed our industry and will continue to do so.”

The world stage

The steel and ferrous scrap industries have pricing that is global in nature, and since half of the world’s steel is now made in China, actions taken in that country continue to affect what happens in North America.

As 2016 enters its fourth quarter, steelmakers in China continue to produce as much steel as they did earlier in the year, even though many voices in that nation’s own government have acknowledged a severe steelmaking overcapacity problem.

For the North American scrap sector, China’s steelmaking overabundance hurts on two fronts: 1) its excess steel capacity brings down finished steel prices, thus putting a lid on scrap prices; and 2) because China’s steel capacity is more than 90 percent basic oxygen furnace (BOF) rather than EAF, it’s appetite for scrap is limited.

To the second point, even though China has for many years had a scrap deficit and has become by far the world’s largest steelmaker, it seldom has been one of the top three buyers of American ferrous scrap.

In the first six months of 2016, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures published by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), China was the seventh leading export destination by volume for outbound U.S. ferrous scrap.

Even if North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) partners Canada and Mexico are removed from the equation, the 273,000 metric tons of ferrous scrap shipped to China lags behind Turkey, which purchased 1.48 million metric tons; India, 675,000 metric tons; Taiwan, 600,000 metric tons; and South Korea, 408,000 metric tons.

Regarding Chinese steel capacity, 2016 has consisted of ongoing global disappointment in the Chinese government’s willingness to keep propping up state-owned enterprise (SOE) steelmakers widely considered by steel industry analysts to be unprofitable and incapable of competing with well-run private steelmakers.

In late September, China’s State Council approved the merger of two SOE steelmakers (Shanghai-based Baosteel and Wuhan-based WISCO), but the announcement made no reference to any resulting capacity cuts.

The situation in China’s steel sector has made steelmakers and their trade associations in other parts of the world among the parties most loudly urging national governments to reject the notion of China achieving “market economy status” within the World Trade Organization (WTO) framework.

In December 2016, when the WTO is scheduled to make that determination, steelmakers and scrap recyclers will be among the interested parties.

Explore the December 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta

- MTM Critical Metals secures supply agreement with Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations