The biggest challenge facing tire recyclers today is the uphill drive to value-added, higher-profit markets for the tires they process.

The biggest challenge facing tire recyclers today is the uphill drive to value-added, higher-profit markets for the tires they process.

“We are looking for uses that get more value out of the tires than single-pass shredding [applications do],” says John Sheerin, director of end-of-life tire research for the Rubber Manufacturers Association, Washington.

On the list of key scrap tire end markets are civil engineering uses, tire-derived fuel (TDF) and ground rubber applications.

Recyclers are putting money into scrap tire processing and want to get value in return. However, the physical amount of tires being retired for recycled is down, and yield seems to be declining as well.

Rolling in more slowly

Regarding the decline in scrap tire generation, “It’s the economy,” explains Brett Barstow, owner and CEO of Golden By-Products, Ballico, California.

“A few years ago, the average weight of a (recycled) tire was 20 or 22 pounds. People are driving their tires an extra few months, and the tires are coming to us in the 16 pound range.”

Add to shrinking size of scrapped tires the aggressive purchasing by off-shore brokers, who ship tires to China and Korea, and the pressure on recyclers has become intense.

Most tire recyclers make their money from tipping fees collected from tire shops and other establishments that dispose of tires. Typically, that fee runs from $1 to $1.25. Some tire recycling companies in need of material may drop their fees to 90 cents, sources say.

Most tire recyclers make their money from tipping fees collected from tire shops and other establishments that dispose of tires. Typically, that fee runs from $1 to $1.25. Some tire recycling companies in need of material may drop their fees to 90 cents, sources say.

However, demand for TDF in Asia has been extreme over the past few years, and some off-shore brokers were charging tipping fees as low as 40 cents per tire. Recyclers in California, Texas, New York and Florida simply could not compete. Eventually, California passed a measure to close nonpermitted buyers, which helped somewhat.

China’s Operation Green Fence also helped to stymie the undercutters.

“We felt a quick hit a couple of years ago,” says Mark Rannie, vice president of Emanuel Tire LLC, Baltimore.

Emanuel Tire processes more than 16 million tires annually and has a retail arm that sells tires as well.

Rannie credits the Washington-based Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) and state lawmakers for putting the illegal operations out of business.

“They couldn’t hide,” Rannie says.

Emanuel Tire, founded by Norman Emanuel, has a solid business supplying TDF and produces a large volume of colorized playground chips. The company also produces crumb rubber, taking the material to a size of five-eighths-inch minus.

Emanuel Tire also is fortunate to have business in the TDF market; in some areas of the country, this market is fading, sources say.

“TDF is a thing of the past out here,” says Pete Daly, general manager at RB Recycling, Portland, Oregon. “You might find some whole tires in cement kilns, but the last mill quit burning a while ago.”

Today, RB Recycling sends all of its crumb rubber to its sister operation in McMinnville, Oregon, where the product is turned into crumb rubber. The company produces 35 million to 40 million pounds of crumb rubber per year.

RB Recycling hauls about one-quarter of the incoming tires, while the rest comes from large chains and other regular suppliers, Daly says.

An operation like Golden By-Products needs 25 million tons of product annually for its business.

“For a while, it seemed all the tires were going offshore,” Barstow says.

“We started in this business 17 years ago, and it’s like we’re starting all over,” he continues. “It’s become a game of who can hold their breath long enough to stay in business.”

Sources say they hope that, as the economy improves, the number of scrap tires and the weight per tire might go up.

Markets certainly exist for those tires.

Up in smoke

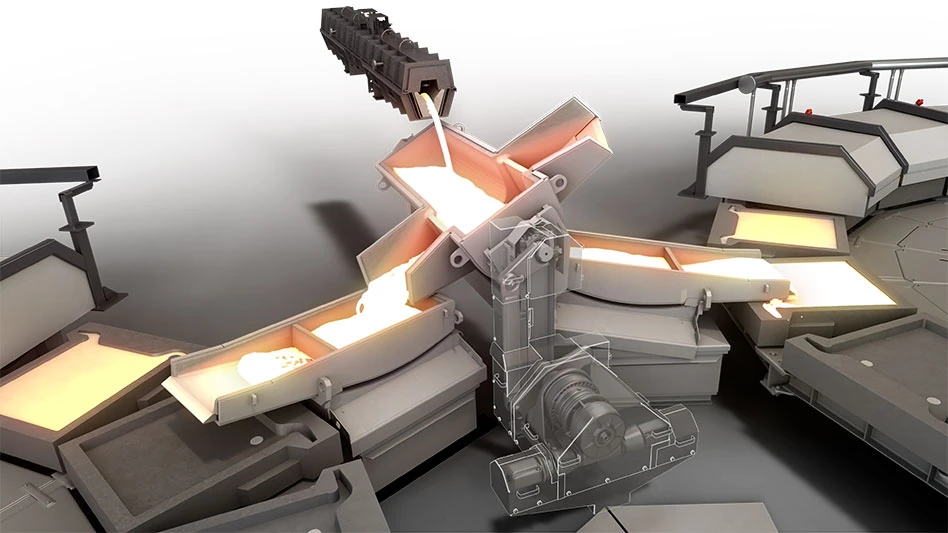

The newest market is chemical processing, or what used to be lumped under the term pyrolysis, the thermal decomposition of the volatile components of an organic material.

Gasification is the next step beyond pyrolysis, though it is not yet consuming what would be deemed a considerable quantity of scrap tires.

The potential, however, is there. “Gasification is poised to make an impact,” Sheerin says.

The potential, however, is there. “Gasification is poised to make an impact,” Sheerin says.

The wild card is neither tire supply nor technology. The success of gasification, which occurs in a higher temperature range than pyrolysis with very little air or oxygen, depends on the cost of energy.

When energy prices hit highs in 2014, gasification looked much more attractive from an economic point of view.

“The whole TDF field is either going to prove up or fizzle out,” Sheerin says, noting that realistic technologies are available for processing tires to fuel. The question is whether the price of energy will justify the investment.

Rubber meets road

State highway engineers seem accepting of rubberized asphalt, Sheerin says, and it is a more profitable use of scrap tires than using them for daily cover at a landfill.

As state departments of transportation have become more comfortable with the material, rubber-modified asphalt (RMA) has seen steady adoption as well as regulatory approval.

|

On the books Colorado became the latest state in the U.S. to enact tire legislation. Under its new law, signed last summer, tire monofills cannot accept tires after Jan. 1, 2018. They will have to close and be cleaned up by 2024. In the meantime, landfills can take in only one tire for every two tires removed for recycling. Beginning Jan. 1, 2018, Colorado’s tire tax at the point of purchase will decline from $1.55 to 55 cents per tire, and the state will distribute the revenue among three new funds. The funds are designed to encourage market development and to provide money to the newly created Waste Tire Administration and Enforcement Cleanup Fund. Laws such as Colorado’s can cause temporary dislocations in markets, however. Pete Daly, general manager at RB Recycling, Portland, Oregon, says a lot of money was made in the tire recycling business when Washington and Oregon passed measures requiring tire stockpile cleanup. At the time, a recycler could get $1.50 or even $2 for a tire. As things returned to normal, many of the boom-time tire recyclers went belly up. “Most were not set up for the long haul,” Daly says. |

Pittsburgh-based Liberty Tire and Lehigh Technology of Tucker, Georgia, signed an agreement earlier this year to expand sales and service for Rheopave, a RMA product, developed by Lehigh, made from micronized rubber powder (MRP). The two companies say Rheopave offers a superior solution for improving the sustainability, economics and performance of RMA.

Under the agreement, Liberty Tire Recycling provides sales, service and support for Lehigh Technologies’ Rheopave RMA systems throughout certain regions in North America.

Rheopave is a blend of polymers and other components to enhance the performance of rubber powders in RMA systems.

“Rubberized asphalt is longer lasting, safer, less costly and friendlier to the environment, which aligns with Liberty Tire’s commitment to reclaim, recycle and reuse,” says Doug Carlson, Liberty vice president of asphalt products.

“Partnering with Lehigh to offer sustainable technologies like Rheopave emphasizes both Liberty Tire’s and Lehigh’s pledge to the environment,” he continues.

Ryan Alleman, sales director for Lehigh, says, “Combining our companies’ capabilities enables us to broaden the reach for an important technology. Together, we hope to make Rheopave the performance standard for RMA systems and to offer solutions to segments that are currently served only by polymer-modified systems.”

Ground down

Ground rubber for molded and extruded products continues to be a solid market for tires.

This is no easy market to crack, however. A company like Golden, fully integrated from pickup to manufacturing, operates with a major capital investment. According to Barstow, the company has equipment totaling 4,000 horsepower, mainly in the 12 shredders it operates. “It’s expensive,” he says.

Given the competition from overseas and the weaker economy, Golden is processing about 3 million tires annually, down from the 4 million tires it processed in 2009.

The company’s products goes to molded items and mats, including rubber equine stall mats, as well as Rubber Bark landscape mulch and playground mulch.

All across the country, tire recyclers still face some questions about the possible health effects of rubber from scrap tires used in turf or as playground base. Most of the questions revolve around the possible carcinogenic impact ground rubber could have on children or athletes who play on such surfaces.

The Rubber Manufacturers Association maintains that there are no health effects from ground rubber based on the scientific studies completed to date.

“We are confident that the science will not change and the dark cloud (of health concerns) will be removed,” Sheerin says.

Another concern is whether the industry can continue to meet the quality needs for playground fill. The major issue here is metal splinters. However, the better processors have solved that issue and can produce a clean, metal-free, grade A product for playground fill and a grade B product that goes to other uses.

Market outlook

Despite the decline in scrap tire generation, “We still have more scrap tires than markets,” Sheerin says.

Emanuel keeps a close watch on the yield of the tires it processes. Rannie recalls being one of the companies that worked with RMA on its study of tire weights. “Forever, we had used a 20-pound value,” he says. After the study, the company began using a 22-pound figure.

Rannie says he is aware that people are driving longer on tires. However, he says he believes the larger tire sizes more common today more than make up for the extra wear. “We are seeing fewer 13 inchers and more 16s and 17s,” Rannie says.

Even though there is not a lot of competition for tires in the Pacific Northwest, there is not a lot of market flexibility, either. “We have not raised our tipping rates in 10 or 12 years,” Daly says.

Although RB Recycling keeps two shredders, four granulators and a pair of cracker mills busy 24 hours per day, five days per week, there has been little sign of boom times ahead.

“The export markets are down. I don’t see much change,” Daly says.

“The truck tire market is more of a challenge,” Rannie says. He notes that people are playing with tipping fees that and truck tires are more difficult to get.

Scrap tire volumes were squeezed by the recession in 2004 and until 2009 as people rode their tires down to the tread wire. While supply bounced back starting in 2010-2011, it is not where it used to be. Processors are not getting the yield they used to get.

The decline in the TDF market surprised many, Barstow added. “Tires definitely will burn hotter and cleaner than coal,” he says, comparing his product to its biggest competitor. In fact, the heat content of coal is in the 12 Btu (British thermal units) range, while a tire is in the 14 Btu range.

“That shows the need for TDF,” Barstow says, noting that tires do an efficient job of offsetting coal usage.

However, the U.S. has mothballed many coal-fired power plants, and consumption of TDF went with them, sources say.

Despite these setbacks, tire recyclers like RB Recycling, Golden By-Products and others are prepared to tighten their belts and go for the value-added markets. While nobody sees smooth sailing ahead, most say they believe there is a future in weathering the current storm.

The author is a contributing editor to Recycling Today and can be contacted via email at curt@curtharler.com.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the July 2015 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta

- MTM Critical Metals secures supply agreement with Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations