Recycling company Müller-Guttenbrunn Group (MGG), headquartered in Amstetten, Austria, and founded in 1954, has a history of scrap metal recycling. Not surprisingly, this emphasis has led to a particular focus on the growing stream of obsolete electronics generated throughout Austria.

Recycling company Müller-Guttenbrunn Group (MGG), headquartered in Amstetten, Austria, and founded in 1954, has a history of scrap metal recycling. Not surprisingly, this emphasis has led to a particular focus on the growing stream of obsolete electronics generated throughout Austria.

The company has invested to develop its recycling processes across the multiple streams of materials electronic devices contain.

Engineer Herbert Müller-Guttenbrunn founded the privately owned company, which is now managed by third-generation family member Christian Müller-Guttenbrunn, CEO of the company.

Across its various facilities, MGG recycles roughly 850,000 metric tons of materials per year, including ferrous and nonferrous metals and plastics. In all, the company operates nearly 20 facilities in Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Switzerland.

In Austria, Metall Recycling Mü-Gu GmbH is MGG’s ferrous recycling arm, handling end-of-life vehicles, electronics, appliances and other types of metal scrap. It also operates a specialized recycling process for obsolete electronics that accepts material from other MGG facilities and from external suppliers for further processing.

Metran Rohstoff-Aufbereitungs GmbH, the nonferrous metals recycling division of MGG, similarly handles processed e-scrap from across the MGG portfolio of companies and from other companies across Europe.

In 2004, the company formed the joint venture business MBA Polymers Austria in Kematen an der Ybbs, Austria, in partnership with MBA Polymers Inc. The production facility began commercial operations in 2006 and processes large quantities of e-scrap plastics from many electronics recyclers throughout Europe, producing several types of plastic resins.

The comprehensive electronics recycling process MGG and its joint venture operations have created and updated over the past decade have been the subject of numerous presentations and tours, Chris Slijkhuis, public affairs director for MGG, says.

He says one of MGG’s strategic targets over the years has been to improve the depth of the materials it is recovering. “We want to really dig deep to get recovery of the material as far as we can get,” Slijkhuis says. “We believe this is basically the head and heart of recycling,” he adds.

Slijkhuis says MGG has invested in upgrades and innovations to its shredding and sorting processes in recent years, providing capacity and recovery that are nothing short of world-class, particularly for the recycling of small domestic appliances.

Shredding improvements boost downstream recovery

Slijkhuis explains that MGG uses a four-step process, some of which was developed in-house, to recycle electronics.

The process begins at Metall Recycling Mü-Gu with depollution using a piece of equipment patented by the company and known as the Smasher.

The company created its first Smasher unit in 2004, using a large drying drum that was sourced from a nearby apple concentrate factory.

“We took this drum and converted it to a machine to tumble the e-waste,” he says.

Electronics placed in the Smasher and tumbled open up to facilitate the release of such items as batteries, capacitors, toner cartridges and printed circuit boards, without damaging them.

The machine has since been patented by MGG, and Slijkhuis says around 20 sites throughout Europe and the U.S. have since purchased the drum.

In 2013, MGG further updated its Smasher design, introducing the Smasher 2.0, a smaller unit designed to gently remove even more pollutants from electronics, including electronic motors and spools and wood.

He says the Smasher 2.0 tumbles the electronics around until the devices open, the batteries fall out and the capacitors and other items can be removed easily by hand.

These materials are released onto a conveyor belt, where the pollutants are removed by hand, Slijkhuis says. “It’s a very efficient way of getting the pollutants out of the e-waste,” he says.

“Basically all of the pollutants are being taken out,” Slijkhuis continues. “The result is then raw material for our shredder.”

A more recent but related innovation at Metall Recycling Mü-Gu concerns the shredding process. Slijkhuis explains that from 2004 to 2011, the company scrutinized its shredding process, particularly for small domestic appliances.

“We realized we could do better in terms of ferrous metals and avoiding the loss of copper and precious metals,” he says. Additionally, Slijkhuis explains, MGG realized during those years that the plastic stream also could be improved as part of the shredding process.

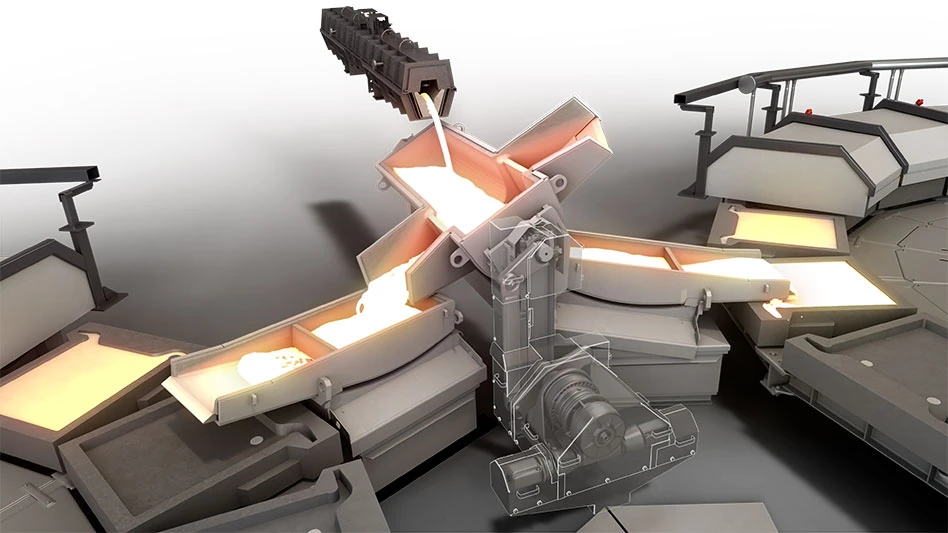

The company’s work in this area led to the 2012 introduction of the EVA shredder, which Slijkhuis says is a combination of several techniques on the market, arranged in a specific configuration and followed by a multistage magnet system for ferrous removal.

Slijkhuis says EVA is the abbreviation for the German term for electronics recycling plant, elektronik verwertungs anlage. It also is named in honor of Eva Müller-Guttenbrunn, the daughter of MGG’s CEO.

He says the EVA shredder is designed to crush electronics very quickly to prevent excessive plastics breakage.

“One of the problems with e-waste,” he says, “is if you hit too strongly on the metals, they will be hammered into the plastics.”

As plastics comprise about 30 percent of e-scrap, “We want to get them out as cleanly and quickly as we can, so that MBA Polymers can make a good separation,” he continues.

In addition, he says, the EVA shredder uses an extremely efficient air treatment system, removing shredded material from the unit quickly.

The multistage ferrous separation process that follows uses a complex magnet separation system that cleanly removes ferrous metals, Slijkhuis says.

The process, he adds, yields a very clean ferrous stream with as little copper and aluminum content as possible.

Slijkhuis explains that the ferrous fraction produced at MGG contains no more than 0.15 percent copper, thanks in part to the EVA shredder and the ferrous separation processes.

“This is important because the copper is more valuable, and it’s also the fraction with which we want to keep the precious metals as well,” he says.

The copper and aluminum fraction is sent to sister company Metran for further processing.

Recovering nonferrous metals

Slijkhuis says MGG’s Metran nonferrous recycling division, founded in 1984, was created to further separate the growing volume of shredded metals the company was creating instead of shipping this material off to another recycler for processing.

The Metran system includes what Slijkhuis describes as a highly efficient heavy media plant built in 2006. The system has three inline drums followed by eddy current separation and sieves.

“We have been able to reduce the smallest size from 5 millimeters to less than 1.8 millimeters by continuous improvements on the FKT process that deals with the small sized material,” he says, adding that the system can separate copper particles well below that size.

“At the end of the process, it gets to a very concentrated copper fraction, and a lot of our effort is really for copper and precious metals,” he says. The facility uses sifting and sensor sorting to yield these results, he explains.

Slijkhuis says MGG’s sensor sorters can sort by color, separating green circuit boards from silver metals, or sorting yellow-orange coppers from yellow-red brasses.

Ultimately, the Metran nonferrous process yields about 10 different streams and many more substreams, Slijkhuis says.

Metran receives mostly bulk-loaded materials, he says, which come from company-owned facilities in Amstetten, from MGG facilities in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Romania and from other companies that send their shredder residue to Metran for further treatment.

Paying attention to plastics

The plastics remaining from Metran’s process are sent to MBA Polymers Austria. The joint venture was formed in 2004 to process the stream of plastics that Slijkhuis says accounts for about 25 percent to 30 percent of the e-scrap stream.

While plastics are not part of MGG’s core business, Slijkhuis relates how the company’s CEO had the foresight to partner with MBA Polymers, a company with experience in plastics recycling.

“The plastic part is an important part of the process, and we wanted to offer more recycling depth,” he says. “We want to separate these materials as far as we can go, and that meant that we needed to add sorting processes for e-waste plastics.”

Slijkhuis says the mix of plastics from electronics is complex. While the majority comprises ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene), PS (polystyrene) or PP (polypropylene), there are also plastics containing flame retardants, which are not recyclable, he explains, and must be removed.

“We start off with a very complex waste that is really junk,” Slijkhuis says, “and by the end of our process, we get to a raw material again that can be used in new electronics.”

Initially, the facility could recover ABS, high-impact polystyrene (HIPS) and PP resins primarily from obsolete electronics. In 2014, MBA Polymers Austria also began producing polycarbonate (PC) and PC-ABS streams. Today, MBA Polymers Austria processes approximately 50,000 tons of plastics per year.

Considering the numerous processes handled by Metall Recycling Mü-Gu, Metran and MBA Polymers Austria, Slijkhuis says MGG is achieving a 94 percent recycling and recovery rate for small domestic appliances. Of the 94 percent of material recovered, he says, 75 percent is recycled, while energy is recovered from 19 percent of the stream. That means the company is reaching European Union recycling targets for 2018 when it comes to small domestic appliances, Slijkhuis points out. It also means the company is achieving significant depth of recycling.

“So many companies that recycle electronics materials just do a tiny bit and send the material to someone else,” he says. “We try to get as much possible material out of it as we can, and that’s what we call recycling depth.”

The author is managing editor of Recycling Today Global Edition and can be reached at lmckenna@gie.net. This article is an edited version of a feature that appeared in the July/August 2015 issue of Recycling Today Global Edition, a sister publication to Recycling Today.

Explore the July 2015 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta

- MTM Critical Metals secures supply agreement with Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations