When Massachusetts’ commercial food waste ban takes effect in October, every business that produces a ton or more of vegetative and food waste will be required to recycle the material. An estimated 1,700 businesses, including restaurants, grocery stores, hospitals and college campuses will be required to source separate organics to be collected and transported to composting and anaerobic digestion facilities.

When Massachusetts’ commercial food waste ban takes effect in October, every business that produces a ton or more of vegetative and food waste will be required to recycle the material. An estimated 1,700 businesses, including restaurants, grocery stores, hospitals and college campuses will be required to source separate organics to be collected and transported to composting and anaerobic digestion facilities.

State officials recognized having collection infrastructure is critical to the success of the ban. While Boston and Springfield have had established collection routes in place, the central part of the state—which included Worcester—was a different story. Massachusetts-based Center for EcoTechnology (CET) was tasked by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) with changing that.

CET has worked with the supermarket chain Big Y since the mid-1990s on waste reduction efforts and already had established organics recycling programs at 28 Massachusetts stores as well as at four Connecticut stores. Expanding its program to central Massachusetts meant finding a hauler. CET approached E.L. Harvey and Sons of Westborough, Mass., and the family-owned recycling company was up for the challenge. E.L. Harvey has been in business for more than 100 years, and, as its Materials and Sourcing Manager Paul Degnan described it, “We have a track record of trying new things.”

During a webinar hosted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in mid-January, Degnan added, “We knew the waste ban was on the horizon, and we were trying to get into it. This seemed like a good fit.”

In addition, Degnan said E.L. Harvey was under significant customer pressure. “A lot of our customers are very educated and wanted to see organics get diverted from the waste stream and use it in the best way possible,” he said. “Many of our customers are sustainability managers at the corporate level and are pushing for zero waste as the ultimate goal, and I think organics diversion/composting plays into that.”

The proposition of collecting organics also was a big opportunity for E.L. Harvey to increase its diversion rate, something Degnan said was core to the company’s business model. “For companies like ours that don’t control disposal sites and are always trying to push for maximum recycling and best use of materials, organics diversion fits into that very nicely.” He added that diversion is a large part of the E.L. Harvey story and is how the company attracts customers and secures them long term.

Learning curve

The goal for E.L. Harvey was to begin organics collection at four Big Y stores in central Massachusetts cities of Worcester, Southbridge, Spencer and Holden and grow from there.

Degnan said there was a definite learning curve in “understanding the unique situation on how organics affect equipment and people,” including how much training sales staff and drivers needed, the types of trucks and containers best suited for the job, maintenance frequency and cost structure.

The first step for E.L. Harvey was defining organic waste, which included:

- food waste;

- agricultural waste;

- animal bedding;

- nonrecyclable paper products; and

- compostable products (plastic items, plastic film/coatings).

Degnan said many institutions were interested in diverting waste from the kitchen as well as from the cafeteria, which meant they had to change their purchasing programs to include compostable flatware and clamshells that met certain standards.

Cleanliness and safety also are important considerations for generators and haulers. Degnan said frequent collections can reduce weight, liquidity and odors. Regular washing of the containers also helps with odors and corrosion. Limiting moisture content by adding nonrecyclable paper and wood shavings, for example, also can help reduce odors and moisture. Some corporate customers produce so much nonrecyclable paper that there are very little free liquids, Degnan noted.

“The cleanliness issue is very important. It is the biggest concern a lot of customers and boards of health have around organics diversion,” said Degnan. He suggested using plastic containers and compostable liners as a way to help the situation.

E.L. Harvey cleans buckets, containers and trucks in a wash bay that cleans, filters and reuses the water to minimize water consumption. Degnan said it helps keep the smell down. “It is actually very important, and the more you stay on top of it, the better off you will be.”

Determining a cost structure was challenging because containers filled with organics can weigh anywhere between 175 to 500 pounds per cubic yard based on moisture content. E.L. Harvey prices out its stops based on time and weight. Degnan said, “Understanding the type of organic waste we are trying to divert helps us establish a price structure.”

When E.L. Harvey began its organics collection routes, it started with a standard box truck to collect material from generators’ buckets and Toters. The truck would pick up loads at a trucking dock or use a hydraulic lift gate. The contents were dumped back at E.L. Harvey’s facility. The material would then be moved again to a composting facility. Degnan recalled it was not an efficient process and required a lot of handling.

E.L. Harvey decided to start using a front-load truck instead. It was a used truck from its fleet with an extra axle to help support the extra weight of the organics as well as seals to hold in liquids. The company fabricated a unit on the front of the truck to dump buckets. “Now we could dump buckets or front-load containers on this route,” explained Degnan.

Consistent service

Finding a home for the organics also required E.L. Harvey to do its homework. The recycling company serves only as a hauler for organics and had to look for composters in the region that could handle the loads it collected.

“We don’t control the final disposal site,” said Degnan. “We think that is a benefit. We are not in the disposal business, so the more we can work with our customers to be a full-service recycler and handle organics, the better off we are.”

Luckily, several options were available for organics in the region. It was simply a matter of which operation would allow for regular deliveries and be the most forgiving when it came to contaminants, which are extremely common in postconsumer collections, he said. Farm-based and industrial composters were potential outlets for the material.

Luckily, several options were available for organics in the region. It was simply a matter of which operation would allow for regular deliveries and be the most forgiving when it came to contaminants, which are extremely common in postconsumer collections, he said. Farm-based and industrial composters were potential outlets for the material.

After weighing its options, E.L. Harvey decided to go with an industrial composter based in Marlborough, Mass., because of it could tolerate a higher level of contamination in the organic material.

“We found that many of the farm operations that wanted the product weren’t always as consistent as we needed them to be,” Degnan explained. “If we are going to pick it up multiple times per week, we can’t keep the material in the truck or dump it on site,” he added.

Degnan noted that the industrial composter was more expensive but that its ability to regularly accommodate the material and allow for contaminants outweighed the alternative. He said the commercial composting facility presorts the material before feeding it into a 100-foot-long digester tube, where it is turned and combined with biosolids for three days.

“This really helps with the compostable plastics,” he said of the digester. “Whereas the farm type composters struggle to hit the temperature and moisture point where the compostable plastics start to breakdown, the industrial composter and the digester really help to speed up that process,” Degnan said.

After the first digestion, the material is screened, turned and windrowed for 90 days before being hauled to another outdoor facility, where it is windrowed and turned for another 180 days.

He noted, “Even after all that time, the product is still ‘just OK.’”

While farm-based composting may produce a higher quality product, the industrial-grade compost is suitable for commercial land applications, slope stabilization and highway landscaping.

While still largely in its early stages, the organics collection for central Massachusetts seems to be working, meaning generators can comply with the upcoming ban. That was the intent of the pilot project with Big Y, CET and E.L. Harvey.

Sean Pontani, CET green business support manager, affirmed, “When the ban does eventually take effect, there will be options for generators across the whole state.”

The author is a managing editor for the Recycling Today Media Group and can be reached at ksmith@gie.net.

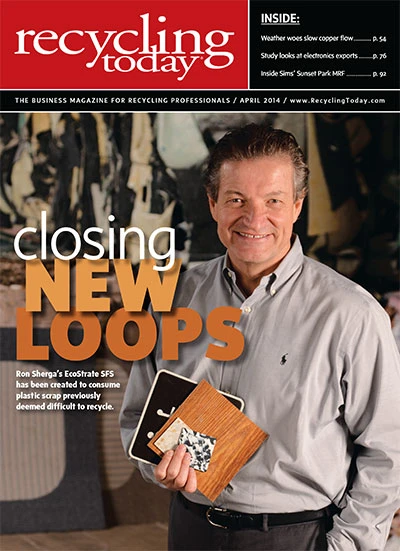

Explore the April 2014 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- OnePlanet Solar Recycling closes $7M seed financing round

- AMCS launches AMCS Platform Spring 2025 update

- Cyclic Materials to build rare earth recycling facility in Mesa, Arizona

- Ecobat’s Seculene product earns recognition for flame-retardant properties

- IWS’ newest MRF is part of its broader strategy to modernize waste management infrastructure

- PCA reports profitable Q1

- British Steel mill subject of UK government intervention

- NRC seeks speakers for October event