If MRF operators can respond effectively to processing “all bottles,” will plastics recycling rates rise?

Recycling rates, in most communities, have reached a plateau. To the general public, the curbside and drop-off recycling programs that were started in the last decade have proven sufficient to solve the landfill crisis.

In their eyes, recycling should now be like any other utility service – provided reliably at the lowest-cost possible. This ideal has not been lost on legislators and other elected officials, so recycling program managers are being asked to become more cost-effective so that funds can be freed up for other areas, such as public security.

Why The Interest?

In this cost-conscious era, recycling coordinators are looking for no-cost or low-cost ways they can get more material in the recycling bins. Changing the community recycling programs to accept “all plastic bottles” does just that, advocates of this approach contend.

Have generation amounts or markets for #3-#7 bottles suddenly expanded? No, but let’s face it, the numbering system for plastics that has traditionally been referenced in most recycling education materials is confusing to a large percentage of people.

Alternative education messages that may have worked well when recycling programs first started, such as specifying “beverage and detergent” bottles, haven’t kept up with the growth of plastics in packaging other products. Recycling program managers are commonly asked: “Why can’t I put a #2 butter tub in the bin? Isn’t it the same as a #2 detergent bottle?” and “Can I put this spaghetti sauce jar in the bin? It says it’s made out of PET?”

As most recycling experts would agree, the easier and less confusing one can make recycling programs for the public, the more successful those programs will be in recovering desired recyclables. Research has demonstrated that collecting all plastic bottles eliminates much of the confusion associated with plastics recycling, resulting in increased participation in programs and recovery of marketable plastics. Furthermore, changing to collect all plastic bottles can rejuvenate existing recycling programs, giving a boost to recovery amounts for all materials. It is thought that any recycling program change and/or educational push reinforces the importance of recycling, which motivates people to start recycling or to be more diligent in getting all of their recyclables into the bin.

WHAT HAPPENS AT THE MRF?

Before addressing the impacts of collecting all plastic bottles on materials recovery facilities (MRFs), it is useful to have some background information on the relative generation levels of #1 PET and #2 HDPE bottles (the types of plastics targeted by most community recycling programs) compared to other types of plastic bottles. PET and HDPE bottles represent 95 percent of all bottles sold – other types of bottles are simply not that common.

This would seem to indicate that one should expect an increase in the contamination of the incoming plastic bottle stream by asking for all plastic bottles. However, in practice the opposite has proven true. In 1997-98, the American Plastics Council (APC) characterized, in detail, the plastics received at six U.S. MRFs.

That study documented the underlying confusion of the public in communities that used the plastics numbering system for targeting PET and HDPE bottles. Programs targeting only #1 PET and #2 HDPE received the same percentage of #3 through #7 bottles as the all bottle programs, and on average received three times as much non-bottle rigid containers. Overall, PET and HDPE bottles constituted 93 percent of the all-bottle program plastic stream, but only 89 percent in the PET and HDPE-only program stream. In other words, the actual impact of all bottles programs on plastics contamination was to reduce the amount of non-bottle contaminants.

The foremost impact of all plastic bottles programs on processors is that the amount of plastics (and initially other materials as well) that is delivered to processing facilities increases. Although this may result in a slight increase in processing costs, processing more material generally makes facilities more efficient and allows fixed costs to be spread over more tons. Recovering more marketable material is a good thing – it is the whole point of recycling programs in the first place. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, plastics reject and residue rates don’t normally increase, while the collection of desired plastic bottles can improve some five pounds per year per household.

Data has been gathered from 11 different communities across the U.S. with programs that collect all plastic bottles – three in bottle bill states and eight in non-bottle bill states. These figures show a larger collection increase was seen in programs located in bottle bill states than in non-bottle bill states – 44 percent compared to 13 percent.

The larger impact in bottle bill states is because soft drink bottles, which are recognized by nearly everyone as a desired recyclable item, are removed from the residential recycling stream in bottle bill states.

This magnifies the effect of recovery improvements for the remaining items. Individual program increases varied from the single digits to as high as 50 percent (a community located in a bottle bill state.)

Due to the variation among communities and recycling programs, analyzing basic information such as plastic bottle generation, recovery and capture rates can help in producing good estimates of anticipated increases before recycling education materials are changed.

Processing Options

There may not be a need to change processing practices or markets when a community goes to all plastic bottles collection, because the percentage of PET and HDPE bottles in the incoming plastics stream generally stays the same or increases. Existing protocols at the MRF for handling contaminants need to be left in place.

Regardless of whether any recycling program changes are anticipated, it is always a good idea to periodically re-examine market options and processing practices to evaluate whether making a change will reduce facility residue rates and improve the bottom line. Creating a cost allocation model for the facility can be very useful in this analysis.

Markets for sorted and separately baled #1 PET and #2 HDPE plastic bottles are numerous and stable, and most processing facilities that receive commingled recyclables sort plastics into streams of PET bottles, natural (uncolored) HDPE bottles and pigmented HDPE bottles. Alternatively, markets for sorted and separately baled #3 PVC, #4 LDPE (low-density polyethylene), #5 PP (polypropylene), #6 (polystyrene) and #7 (other) are much harder to find. Furthermore, because those types of plastics are found in much lower quantities than PET and HDPE bottles (less than five percent of all plastic bottles), only the largest facilities normally even consider devoting sorting station, bunker and bale storage space for those resins. A rule that can be used for a quick evaluation of sorting out other plastic bottle types is: If you ship a load of pigmented HDPE bottles once per month, it will take you a year to accumulate enough PVC bottles (or PP bottles) to make a shipment. The other types of bottles are found in even lower quantities. Polystyrene bottles (other than the small pill-bottle size) are virtually nonexistent.

Some processors who sort plastics into PET and HDPE streams are able to include #4 LDPE, #5 PP and most #7 other plastic bottles in with HDPE bottles. HDPE, LDPE, PP and most #7 bottles are closely related and are part of a similar class of plastics called polyolefins. Think of them as first cousins. As long as the number of bottles that are #4, #5 or #7 doesn’t become too large of a percentage of a HDPE bale, it is normally acceptable to include them in with the HDPE bottles.

The ultimate end markets that turn the recycled HDPE into new products, however, do have different tolerances for this practice. Be sure to check with your market before including #4, #5 and certain #7 bottles in with HDPE bottles.

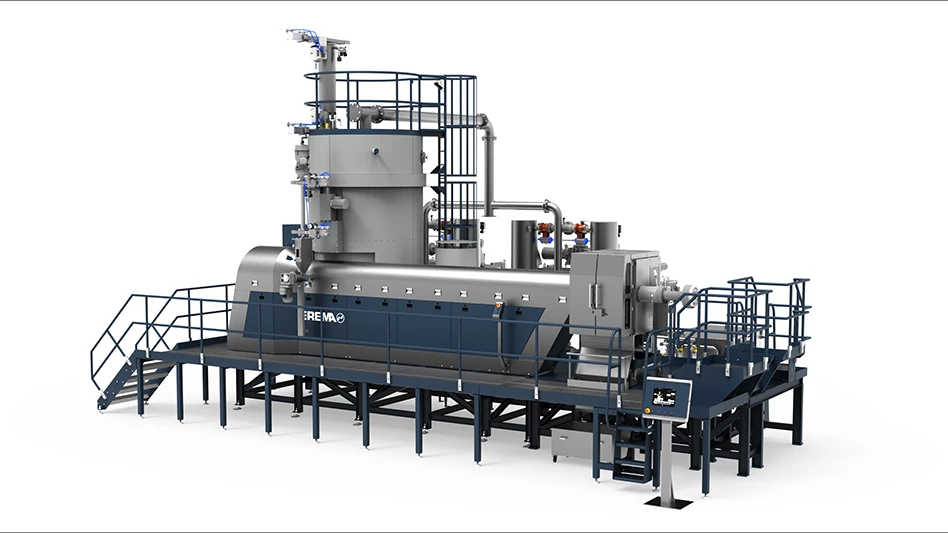

Markets for baled mixed plastic bottles are limited to a handful of U.S. companies and an assortment of exporters. The most publicized and, by far, the largest mixed bottle market is Waste Management’s PREI facility in North Carolina.

This facility, which at press time was being upgraded to increase its capacity, and one or two others like it use automated equipment to sort plastics more accurately and more cheaply than can be done by hand. Although Waste Management owns the PREI facility, its business plan calls for more material to be supplied from MRFs not affiliated with the company than with material supplied from Waste Management’s Recycle America facilities.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

To date, marketing baled mixed plastic bottles has been most popular with three types of processors:

• those who have small facilities that are not well-equipped for numerous sorts or that don’t receive much plastics;

• those who receive plastics already separated from other materials (most often from curbside sort or drop-off programs); and

• those with large and highly mechanized systems that use screens, blowers, and magnetic/eddy current separators (such as are found in single stream processing facilities) to achieve material separation.

In summary, accepting recyclables from programs that specify “all plastic bottles” in the education materials doesn’t mean there has to be a change in how recovered materials are processed.

In fact, because the percentage of PET and HDPE bottles in the plastics stream generally stays the same or increases, most facilities that receive all plastic bottle plastics don’t change their processing practices or markets after changes are made to recycling education materials. However, some community recycling program managers strongly prefer that processors market all materials listed in the community’s education materials (i.e., all plastic bottles) in order to avoid any appearance of misleading the public.

Ultimately, all communities and processors must assess their goals in deciding how simplifying the recycling message to all plastics bottles will individually affect them.

One thing is almost certain – given the ability of all plastic bottles programs to improve recycling diversion at little or no additional cost, interest in all plastic bottle programs will continue to grow.

Specific questions can be directed to the author of this article. The author is a senior project manager with R. W. Beck Inc. in its Orlando office and provides plastics recycling technical assistance on behalf of the American Plastics Council. He can be reached at tbuwalda@rwbeck.com or (407) 422-4911.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the January 2002 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Green Cubes unveils forklift battery line

- Rebar association points to trade turmoil

- LumiCup offers single-use plastic alternative

- European project yields recycled-content ABS

- ICM to host colocated events in Shanghai

- Astera runs into NIMBY concerns in Colorado

- ReMA opposes European efforts seeking export restrictions for recyclables

- Fresh Perspective: Raj Bagaria