I have been professionally focused on hard drive sanitization for 11 years. Throughout that time, the most common theme I have observed, especially in the electronics reuse community, has been that organizations’ priorities related to data destruction decisions almost always are reactive to new information irrespective of relevance. In other words, decision-makers have a habit of reacting to the newest piece of information—be it a new standard, guideline or even press release or marketing message, and reviewing their data destruction operations with the new information as a top priority, sometimes to the point of losing sight of much more critical considerations. Unfortunately, this practice is extremely ineffective and often unnecessarily expensive.

Let’s start with an example (or a symptom, depending on how you look at it). When discussing a media sanitization process with someone in the industry, whether a client, partner or otherwise, what kinds of questions do we most often ask?

“What software do you use?”

“How many passes do you do?”

These questions are about a mechanism involved in the data wiping process: the software. They are all about one of the tools used in the process of wiping drives.

I’ve never heard someone ask, “How often do your technicians go through retraining on sensitive data handling practices?” Or, “What procedures do you use to separate unwiped, passed and failed devices?”

If I told you that this latter set of questions points to areas of a data wiping operation that are more than 10 times as likely to cause a breach-level failure than the former set of questions does, would you believe it?

Maybe not.

Let’s look at it a different way. If you were hiring a contractor to build an addition on your house, you’d ask for insurance information, check BBB ratings, ask for some examples of recently completed projects and maybe some customer testimonials.

What you wouldn’t do is ask, “What brand of framing hammers do you use?” or, “What kind of tires do you have on your utility vans?”

However, this is exactly how misdirected our priorities can be when it comes to data destruction.

To focus on one of the tools used to perform one of the tasks associated with the data destruction process is incredibly shortsighted. More than that, it’s misguided. Based on more than a decade of experience solving problems wiping drives, I can say with confidence that the brand of data wiping software or the erasure algorithm being used aren’t near the top of the list of critical elements of an effective overall media sanitization process. How did our priorities become so out of order? The short answer: marketing.

It’s not surprising that the more often something is repeated or the more loudly it is stated, the more relevant that thing appears to be. If you need any evidence of that statement, critically review any recent “scandal,” whether it be sports, politics or any other polarizing field. It’s “more probable than not” that, through unbiased analysis, you’ll see a massive gap between the conveyed magnitude of a particular fact or allegation and its real-world importance.

Back to data destruction, in the U.S. in particular, we only have general guidelines to help us make decisions about how to wipe data from electronic storage media. We don’t have any commercial certifications for data wiping tools (which provide nominal value, anyway), and the only process certifications for data wiping, in my experience, tend to permit some dangerous behavior (unsupported or out-of-date data wiping tools, nondescript device handling practices, marginal personnel training, etc.). We’re left with little dependable guidance as to what really matters when it comes to the process of wiping drives. Data wiping software companies are, of course, obliged to answer the call for guidance.

“What’d I miss?”

I’ve seen data get out many times. We call it a breach-level failure. I’ve seen unsanitized drives shipped to customers, despite having been “successfully wiped.” I’ve analyzed how and why it happened and helped organizations take corrective action and eliminate the original vulnerabilities that led to the process failures. The causes for the various failures have varied somewhat, though they all share one commonality. We’ll get to that later; but first, the causes.

Software. We’re generally conditioned to believe that if a reputable data wiping software reports a successful or “passed” wipe, then the drive has indeed been wiped successfully using the specified erasure algorithm. No original user data should remain on the drive. From repeated personal experience (especially since the Validator was introduced), I’ve witnessed multiple versions of multiple brands of professional, popular data wiping software tools report successful wipes in the field and found the drives to not only contain logical user data but in some cases to not have been wiped whatsoever. In one instance, the same software vulnerability existed for nearly two years without a recall, bug fix or even a technical bulletin or guidance document from the developer.

In no other industry will you find a critical process executed with the kind of blind faith that data destruction professionals place in the erasure results reported by data wiping tools. Perhaps most interesting is that even while we impugn the security reliability of multibillion dollar software and OS (operating system) providers with massive regression and vulnerability testing budgets, we take as gospel the testimony of a data wiping software that might have been developed by, at most, a handful of engineers in a lab environment that may not even have access to the type of storage we’re wiping. To use a phrase President Reagan famously borrowed, everything we know about the nature of software development tells us we should take a “trust but verify” approach to data wiping.

Media segregation. The majority of cases in which improperly sanitized, failed or entirely unsanitized devices (We often generalize all of these cases as “red” status devices—they’re still likely to contain user data.) have made it through the data wiping process as “wiped” have been a direct result of an individual physically putting unsecured drives in the wrong place. Unloading large quantities of drives from a data wiping appliance or a bank of servers becomes a repetitive task for technicians. It’s not reassuring to consider that, on Thursday, the second-shift technician will put five unwiped drives in the “passed” pile, but most of the time that’s exactly how it happens.

Another cause of failure related to segregating red status devices is a systemic inability to actively track the storage media throughout the wiping process. In other words, how clear is it to everyone in the building when red devices are not yet under lock and key? How much time are these devices allowed to spend in receiving? Which employees may access the red status devices during these times? These are examples of questions that can quickly measure the integrity of a process to determine how vulnerable it is to a media-handling-related failure.

Hardware. The most difficult type of data erasure failure to diagnose is a hardware error. Errors with the drives, enclosures, controllers and the host system can create unpredictable and sometimes inconsistent behavior in the data wiping process. So much so, in fact, that I’ve often coached clients that if the quality control procedure reveals a problem in the data wiping operation that makes no sense, it’s probably hardware-related. As an example, I’ve seen a data wiping system write random, unexpected characters during an otherwise “repeating-sector” wipe because of what we discovered to be a RAM error.

The point is that hardware issues can and do affect the performance of a data wiping operation, and sometimes that impact can be difficult to detect. These errors sometimes can be benign (as in the example above), and, in other cases, they can invite breach-level process failures.

It will happen to you

When I am dealing with another discovered media sanitization process failure, the question I ask most is, “How many times has this occurred prior to discovery in this or any environment?” I often wonder how many people even know to look for a problem like the one we’ve discovered. How many organizations have the tools or processes to detect it?

The next question is, “How many types of process failures have I yet to see? What don’t I know about yet?”

I strongly believe there will never be any reasonable assurance that hardware, software and media segregation procedures will be incapable of repeating, in some form or another, the failures I’ve already seen many times. Furthermore, it stands to reason that each of them will, at some point, exhibit new problems that will need to be solved. Each of these operational elements is a perennial vulnerability in the data erasure process, and any organization that performs data wiping is susceptible to them. However, the fact that there are vulnerabilities associated with the individual elements of a data wiping operation does not mean that the overall process needs to be vulnerable. In fact, recognizing and accounting for these potential weaknesses is, in my opinion, the most important step in building an ironclad data wiping operation.

The bulwark

I mentioned before that, without exception, every breach-level data erasure process failure that I’ve analyzed had one thing in common: It could have been prevented through process, through a systemic, aggressive, realistic set of checks and balances that ensure that the integrity of the entire data erasure operation is not hinged on any single component.

Data destruction professionals must create a process that does not rely on the flawless performance of the personnel or the tools in place. They must create a process that accounts for technician errors, software misreporting and physical security lapses and still functions as needed to prevent such errors from becoming a breach-level failure.

A strong process, of course, requires quality tools and their seamless integration. It requires competent and trained (and retrained) personnel. It requires scrutiny, specificity and scalability in quality control. First and foremost, however, it requires realism on the part of its administrators. Any data destruction professional who believes that, because of the tools they’ve invested in or the manager they’ve hired, their operation is impervious to major security risks has thrown out the linchpin of any strong media sanitization process: vigilance.

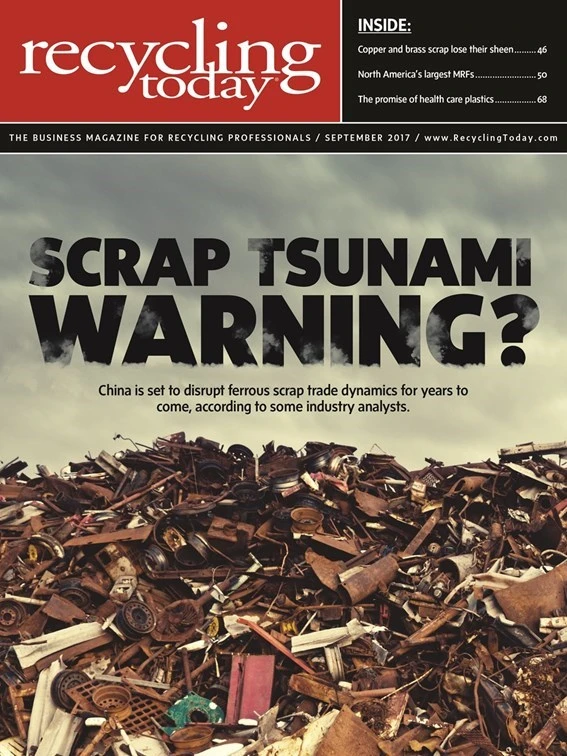

Explore the September 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Hitachi forms new executive team for the Americas

- Southwire joins Vinyl Sustainability Council

- Panasonic, Sumitimo cooperate on battery materials recycling in Japan

- Open End Auto Tie Balers in stock, ready to ship

- Reconomy names new chief financial officer

- ICIS says rPET incentives remain weak

- New Jersey officials award $16.2M in annual recycling, waste reduction grants

- Linder Industrial Machinery announces leadership changes