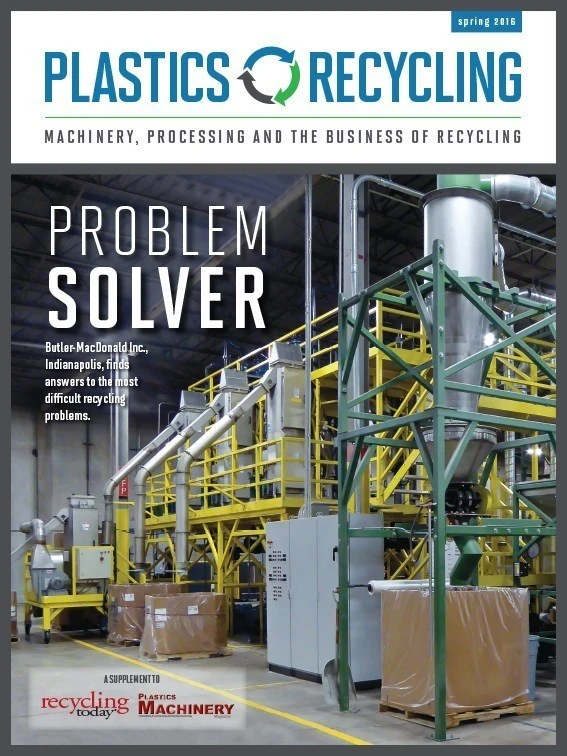

To gain a competitive advantage, postindustrial plastics toll recycler Butler-MacDonald Inc., Indianapolis, finds answers to the most difficult recycling problems, even if the answers don’t come from available plastics recycling machinery and equipment. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Butler-MacDonald’s approach is how much it does to modify equipment once it has arrived in its plant. At its headquarters, the company now has 13 different cells of technology, which is how the company refers to its processing lines. No two cells are the same.

Butler-MacDonald has a 128,000-square-foot facility and about 70 employees. About 95 percent of the total space, including a lab and shipping/receiving department, is for recycling/manufacturing operations. The other 5 percent is dedicated to office areas.

During a recent tour, officials pointed out the pipes that snake across the ceiling—the explosion-suppressant system. Safety is a priority.

“All of our dust collection has an explosion-suppressant system,” says Vice President Tim Cash. “It reads a very sudden spike in pressure. Those will [activate] and prevent an explosion from occurring. For us, dust is a big thing. It is a potential explosive and contaminant. We watch it closely, and we don’t allow it to happen here.”

Butler-MacDonald modifies all of the equipment it uses and is always upgrading.

It does not perform a lot of applications using fibers and films, though that could be in its long-term plans as company officials have looked at different technologies.

“Just buying a piece of equipment doesn’t get you where you need to be,” says Ray Pomerleau, director of plastics. “We can take contaminated scrap and return it to a purity that they can use, pound for pound. We are a plastics recycler with a prime material mentality.”

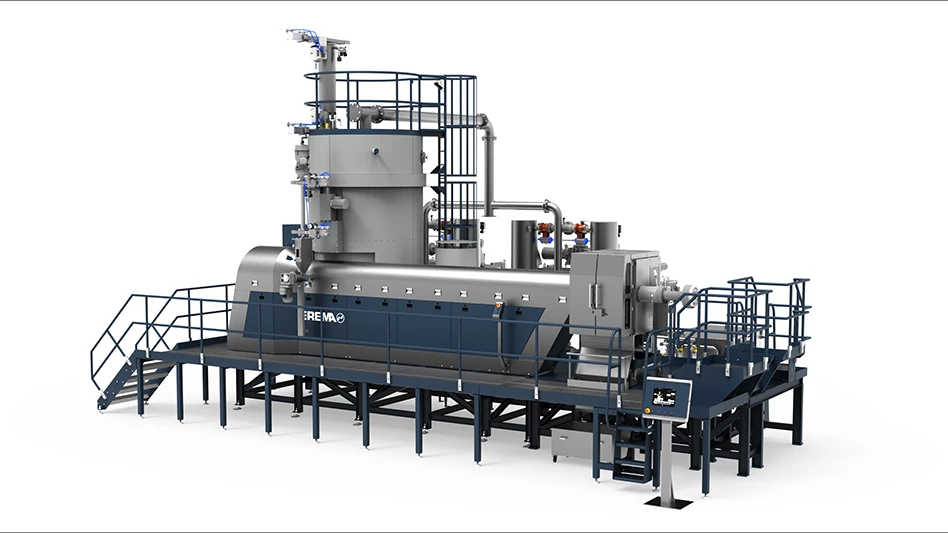

The challenge for Butler is to process the scrap to a higher purity and higher yield than that which is available elsewhere. Within its operations, it has all the types of equipment one would expect. This includes granulators; shredders; an assortment of separation technologies, including density, electrostatic, laser, color, cyclone, hydrocyclone, gravity and zigzag, near-infrared spectroscopy; destoners; melt filtration; metal removal and metal detection; blenders; compounders; pelletizers; extruders; and screens and fines removal systems.

In 2015 the company processed about 40 million pounds, and this year officials say they expect to eclipse 50 million pounds.

“We customize everything,” Pomerleau says. “It is not a cookie-cutter approach. Everything is a new challenge.”

Cash reiterates that point. “Anybody can go out and buy that piece of equipment,” he says. “You are not going to get the same results. That is the knowledge we possess.”

Company officials want Butler to develop into a solutions-based company to be more of a resource for clients. These efforts would include organizing plastics recovery programs.

“It’s being innovative. It is one thing that he pushes us to do,” says Cash, speaking of J. Scott Johnson, the company’s CEO, president and chief system designer. “We are always pushing ourselves to do better.”

The company typically identifies and sells its tolling services one month in advance, which allows it to use groupings of the same material type to maximize the efficiency of each processing run.

Butler prefers loads of 40,000 pounds or larger from its clients in light of the economies it can provide to the clients. However, if it’s a fit in an upcoming program or ongoing run of materials, Butler will accept much smaller amounts of around 10,000 pounds. In between every customer, employees clean the machines.

“It also allows us to make sure a material that we process is followed by a subsequent material that will see the previous material as the contaminant, thereby minimizing the extent of cleaning that will need to take place,” says Johnson.

BEHIND THE WHEEL

Johnson drives Butler-MacDonald. He trained as an audio engineer and went to school to study architecture, but life’s path took him into plastics. He is forthright about pushing the company in new directions and about how Butler is adapting to changing markets. One thing is certain—the company is in growth mode. Officials are selecting a site for a geographic expansion. At a visit in December, officials also said they were looking at adding another line.

“We have a desire to open another facility,” Cash says. Within the last year, the company also has added a new sales director, Bryan Johnson, two new account managers and two production supervisors. Butler has a goal of doubling its sales team within the next two years.

Johnson admits that his company is very discerning when it comes to machinery and equipment. New equipment always is entering the market, he acknowledges. That doesn’t mean Butler will buy.

“There are pieces of equipment that are, for example, designed or targeted specifically for recovering plastics from the refuse-recovery market,” he says, “While we are aware of and understand the need for this class of machinery, we would not purchase or otherwise try these machines because the accuracy and quality of the end product is not pure enough for our customers’ needs. We specifically look for machinery that we can fit into our overall objective of producing consistent, high-quality material.

“My best vendors are the people who don’t come in and try to sell me on price,” Johnson says. “I’m looking for solutions. I’m not looking for a price. What do they think they can do? We’re a very difficult sell. We take a long time to make decisions. We are far more interested in pushing the limits with everyone’s technology and exploiting it. The more people become educated, the more they think you shouldn’t do things. Somehow, throughout all the years, we’ve been able to evolve.”

“My best vendors are the people who don’t come in and try to sell me on price. I’m looking for solutions. I’m not looking for a price.” – J. Scott Johnson

He uses the example of granulators for how he analyzes a specific piece of equipment, looking at the knives that are used, angles and the speed of the rotor. Johnson will tear the equipment apart to the level where he and his team can expose any weakness. He says the company has evaluated almost every style, brand and geometry of granulator to arrive at the specific designs used in-house.

“Over the years, we have settled in on a customized variation of Cumberland granulators and another made by Herbold,” Johnson says. “To these we might change knife geometry or design details about the screens used based upon what we are trying to accomplish. Having studied most manufacturers, what would dictate a change in style or brand would be based upon the opportunity for services.

“We know when to use Granulator A, B or C to get a result,” he says. “We know how to exploit one versus the other.”

Butler-MacDonald helped Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, California, when it could not get the final product it wanted from an inkjet cartridge recycling project. Gates in molds were getting plugged. Everyone thought that a level of metal still existed in the part.

Johnson went out and learned the various merits of each form of metal detection. Then, he said, “What if it is a nonmelt that is plugging the gates?”

Many would resort to melt filtering to remove nonmelts. But melt filtering was not an option because the product contained glass fiber, and melt filtering would remove all the glass fiber. Butler-MacDonald then developed a separation technique that removed nonmelts.

“We like it when it is a difficult separation,” Johnson says, remarking that Butler-MacDonald is known for its sustainability and quality. “That is where we really shine. I think we’ve earned that reputation over all the years.

“We sort of embrace failure,” he says. “We do not run away from it. The people that innovate embrace failure, and I learned that at a very early age. We didn’t know we shouldn’t be able to do what we do.”

EVOLVING TECHNOLOGY

Markets change and evolve, and recycling is not immune to macroeconomic forces. When resin prices drop, for example, and other world events affect inventories and consumption, Butler-MacDonald faces intense pressure to find ways to lower its costs while also maintaining quality for its customer base, Johnson says.

About two years ago, officials became aware of manufacturers with “laser” melt filters for extrusion lines, a technology that could help meet these increasing demands that included lower costs. Johnson is careful to clarify that “laser” filters actually are filters made by electron beam drilling (EBD), a thermal drilling process that punches tens of thousands to millions of holes in a sheet or cylinder that will act as a filter media. Although laser filtration was not new, new designs had entered the laser market and were capable of producing minimal waste.

Butler-MacDonald purchased a filter from Maschinen und Anlagenbau Schulz GmbH (MAS), Pucking, Austria, whose products are distributed in the U.S. through eFactor3 LLC, Pineville, North Carolina. The company retrofitted the filter onto an existing extrusion system.

“Since owning the filter, we have had an ongoing relationship with MAS where we share process information and also discuss design changes,” Johnson says. “These are the relationships we want. The end result is that this specific filter and its technology have enabled us to reduce the overall cost of processing material. While, by itself, it is not the answer for most of the problems we see, when tied to other technologies we use, it makes a big difference in the cost and quality of the end product we deliver.”

SEEKING SOLUTIONS

The end result always is the driving factor when the company purchases machinery or equipment.

“Price and maintenance costs are always down on the list compared to the need to solve a problem,” Johnson says. “From the end result comes commercial viability and whether we think we can get a return on investment based on a need in the marketplace. It’s a struggle sometimes to get the manufacturer to let us worry about the price.”

In another case, company officials found a solution while walking a trade show floor where they found high-dispersion mixers used in the production of mustard and paint pigment.

A wire manufacturer had asked Butler to recover PVC (polyvinyl chloride) from thermoplastic high-heat-resistant nylon-coated wire (THHN), which is a nylon-sheathed, PVC-jacketed copper wire used where there is a need for resistance to oil-based products. The manufacturer wanted to recover the PVC for use back into wire.

This project had a peculiar difficulty. When granulated for copper recovery, the majority of the insulating jacket remained intact, with the nylon stuck around the exterior of the PVC, making the recovery of clean PVC almost impossible.

Butler-MacDonald officials believed that the high-dispersion mixers had properties to create an action that could wash or remove the nylon jacket from the PVC. The machinery manufacturer, however, would not support the application, Johnson says. Butler-MacDonald found a used machine and worked with manufacturer Kady International, Scarborough, Maine, to redesign its main components so the machine could be used to provide the shearing action required.

This is an example of a particularly onerous project. “The end result was an almost total liberation of the nylon outer jacket from the PVC with the added bonus of also recovering several percent of remaining copper tailings from the previous copper recovery operation,” Johnson says. “This opened the door to other washing operations because the friction caused by the shearing action caused the vessel to boil water due to heat generated and eliminated the need for other heat sources.”

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the April 2016 Plastics Recycling Magazine Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Astera runs into NIMBY concerns in Colorado

- ReMA opposes European efforts seeking export restrictions for recyclables

- Fresh Perspective: Raj Bagaria

- Saica announces plans for second US site

- Update: Novelis produces first aluminum coil made fully from recycled end-of-life automotive scrap

- Aimplas doubles online course offerings

- Radius to be acquired by Toyota subsidiary

- Algoma EAF to start in April