Plastic, single-use shopping bag bans have been a rallying point for environmental advocates who see a litter problem that travels by land, air and sea. The thin plastic bags represent just one segment of the plastic films sector, which has an equally wide presence in retail and industrial settings.

Responding in part to negative public relations and to corporate sustainability programs seeking higher recycling rates, plastic film recycling has grown.

On the collection front, warehouse and factory workers (and some members of the public) have been trained to identify plastic films as recyclable. Unfortunately, China’s plastic scrap import restrictions have narrowed end markets for the material, threatening to undo some of that progress.

Opposing the ban mentality

Environmental advocacy groups with differing agendas seem to have agreed that the ubiquitous thin-film shopping bag deserved scrutiny. Throughout this decade, campaigns have been mounted around the world (many of them successful) to ban or heavily tax the bags.

To some extent, plastic shopping bags became victims of their own success. The lightweight bags were energy efficient to transport and required less storage space at retail stores compared with kraft paper sacks. As the plastic bags gained market share, however, recycling strategies lagged.

The empty, discarded plastic bag as an urban tumbleweed quickly gained iconic status. As plastic bag bans and taxes entered the national discussion, municipalities searched for recycling options. Unfortunately, most material recovery facilities (MRFs) are equipped with screens that regard the bags as nuisances that gum up the works—not as recyclables to be added to the curbside mix.

Plastic bag manufacturers added collection bins for used bags at retailers around the United States and helped develop end markets for the recyclable plastic, but the attempts have not yet stalled the ban and taxation momentum.

One of the next adherents to the “ban the bag” mentality is likely to be the commonwealth of Massachusetts, which is considering legislation to ban stores from providing single-use plastic bags starting Aug. 1, 2019.

“Massachusetts residents are estimated to use more than 2 billion bags per year (about a bag per person per day),” states the Massachusetts chapter of the Sierra Club on its website. The bags lead “to pervasive litter,” according to the organization. “This synthetic material does not biodegrade, which means it lasts forever in the environment.”

The publicity and legal battles seem to have helped boost the recycling rate of plastic films, which grew by 10 percent in 2016, according to a report from the Washington-based American Chemistry Council (ACC). Some 650,000 tons of film were collected for recycling in the U.S. in 2016, the ACC report notes.

Based on research conducted for the report, known as the “2016 National Post-Consumer Plastic Bag and Film Recycling Report,” the ACC states that plastic film recycling has grown for 12 consecutive years and has more than doubled since 2005, when the first report was compiled.

Adding to the film recycling success story has been the widespread adoption of sustainability and zero waste goals by corporations around the world.

Cultivating corporate habits

Multinational companies with landfill diversion as a sustainability goal identified plastic film as a material to address.

As early as 2005, global retailer Walmart trademarked the term Plastic Sandwich Bale and worked in partnership with Utah-based Rocky Mountain Recycling on a pilot program the retailer indicated could eventually “keep tons of plastic out of landfills and revolutionize plastic recycling.”

“This program could quite possibly become one of Walmart’s biggest recycling efforts to date,” said Dick Pastor, director of environmental management for Walmart at the time. “We are so happy with the results that we’re adding another 267 stores to the program [in the fall of 2005].”

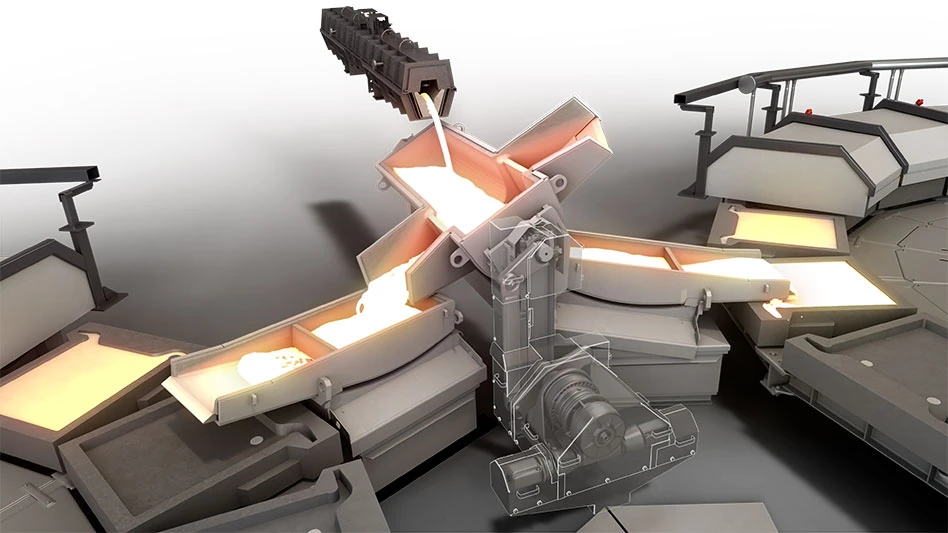

The Plastic Sandwich Bale involves Walmart employees placing 10 to 20 inches of cardboard at the bottom of its compactors, followed by the introduction of “shrink wrap, plastic bags, apparel bags and other loose plastic,” ending with another section of cardboard placed at the top of the compacting chamber.

The bales are shipped to consuming facilities, including makers of plastic lumber and recycled-content shopping bags.

In its 2004 and 2005 pilot testing phase, Walmart diverted from landfill and recycled more than 5,700 tons of plastic, the company indicated in an August 2005 news release. In its most recent sustainability report, Walmart says it diverted 82 percent of materials previously considered waste from landfills at its locations in the U.S. in fiscal 2017.

Detroit-based General Motors (GM) continues to boost the number of landfill-free facilities it operates, with plastic film diversion and recycling part of its process.

A 2015 fact sheet from the company indicates GM “recycled or reused more than 2.5 million metric tons of [discarded] materials at our plants worldwide.”

In February 2018, GM indicated another 27 of its facilities had attained zero-landfill status, bringing the worldwide total to 142 locations.

One producer of plastic films also has been boosting the recycling rate by operating an internal recycling program and by helping its customers find recyclers who will accept plastic film.

Glendale, California-based Avery Dennison produces plastic film products used in numerous packaging applications. According to Heather Valentino, the company’s North America sustainability manager, “In our internal operations, we have been recycling our film material for five years. Based on the success we have had within our own operations, in 2017 we began identifying additional recycling locations to help our customers and end users find recycling outlets.”

Valentino says in 2016 Avery Dennison began to work with sustainability collaboration information provider Ecovadis, with U.S. offices in New York City, “to help us identify and monitor the corporate social responsibility [of most] of our suppliers.” The resulting discussions, she says, “have resulted in multiple activities, such as a returnable packaging program. Within the last six months, we have had a large increase in the number of sustainability requests we have seen from our customers” and their customers, Valentino adds.

Looming over increased collection in 2018, however, are China’s tightened plastic scrap import restrictions. “Recently we have seen some challenges within the market,” she says, adding that some recyclers were scaling back acceptable materials or increasing the minimum quantity they will take in a single load.

Valentino adds, “We are still waiting to see the full impact of the China ban.”

Avery Dennison is not alone.

Unfriendly sailing conditions

When several of China’s central government ministries, led by its Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), began issuing new restrictions and outright bans on imports of certain scrap materials, the plastics sector was hit hardest and most rapidly.

By the spring of 2017, shipping containers full of plastic scrap were being denied entry to the People’s Republic of China at the country’s ports. Later in that year, global trade figures reflected the steep drop-off in shipments.

A November 2017 visit by Recycling Today staff members to a MRF in Warsaw, Poland, demonstrated the sudden change in global plastic film markets.

At that time, Szymon Rytel, who helps manage the Warsaw MRF for Company Bys, said his firm no longer had an end market for mixed-color plastic film bales. Fortunately for Company Bys, the firm also produces refuse-derived fuel (RDF), so it was able to divert the film by mixing it into its RDF product.

Such energy-from-waste prospects could be the fate of more collected film scrap until or unless consumers who had been reprocessing it in China begin setting up shop elsewhere.

Italy-based equipment maker Amut SpA in August announced it had been awarded contracts by two European firms to outfit plants with reprocessing capabilities.

Although it did not name either customer, Amut indicated one plant would be equipped with two production lines, working in parallel, to process LDPE (low-density polyethylene) film scrap at a rate of 5,500 pounds (2.75 tons) per hour. The scrap infeed would consist “mainly of baled blown films coming from postconsumer recycled packaging,” according to Amut.

The other project entails installing twin lines for washing and pelletizing postconsumer LDPE film or polypropylene (PP) or HDPE (high-density polyethylene) containers. That system will handle 3,300 pounds of LDPE film hourly, Amut says.

In the U.S., GDB International, New Brunswick, New Jersey, and Avangard Innovative, Houston, have expanded their operations to produce recycled pellets from the postcommercial and postindustrial film they had previously been collecting, sorting and selling. While Avangard announced the addition of this capacity in early 2017, before China enacted its current import policies for plastic scrap, GDB International made the decision to do so more recently, with the first of its four lines becoming operational in February of this year. (See the cover story, “Taking the next step,” starting on page 34 of this issue for more about GDB’s foray into recycled plastic pellet production.)

Companies based in China that need access to plastic and paper scrap also have begun investing in the U.S., with two such announcements made in the first quarter of 2018. One company that will recycle juice and beverage cartons (which contain polyethylene) is building a plant in South Carolina, while another is setting up a facility in Alabama.

Lily Zhang, CEO of Roy Tech Environ, has told an economic development agency in Alabama that her company would install grinders and shredders for five production lines, followed by the installation of pelletizing equipment. The main grades the company will handle are HDPE, PP and polycarbonate (PC).

Although neither of the two 2018 U.S. investments target plastic film, if the material is going unused and is increasingly affordable, investors are almost certain to find it.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the April 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Unifi launches Repreve with Ciclo technology

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta