Throughout human history, the residuals of daily activities have been disposed of in the easiest and least expensive manner possible, thus ingraining a perception that the stuff we call waste has no value.

The worldwide population is approaching 7 billion people and growing at about 80 million people per year. The superhighways of commerce in the industrialized countries are now filled with the consumer goods of a global economy. However, today solid waste management in many developing countries is at a point where the industrialized countries were a hundred years ago. Methods that were acceptable back then (open dumps and burning) are currently being used around the developing world and resulting in unabated discharge of hazardous and solid waste into the ground, rivers and oceans.

Electronic scrap has been around since the widespread use of electricity and product innovation created the first appliances, radios and TVs. Typically, obsolete electronics have been a component of municipal solid waste, inexpensively disposed of in landfills. This process is an open-loop, single-pass system.

Today, an increasing number of options are available for electronic scrap management. Electrical and electronic equipment that has served its intended first use can now be processed for reuse, recycling and/or end-of-life management in a closed-loop, multiple-pass system.

SAFETY FIRST

Two attributes of electronic scrap define its management issues around the world. The first is the number and variety of toxic materials present in the enclosures and components of electrical and electronic equipment. The second is the value and volume of reclaimable materials (metals, plastics and glass) available for use in new products, which reduces the quantity of virgin, non-renewable, raw materials mined to keep up with ever-increasing consumer demand.

The electronics recycling process has many key players with multiple interactions. Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), consumers, electronics scrap management companies, logistics companies, non-government/nonprofit organizations (NGOs) and government agencies all play a role in the electronics recycling segment.

Electronic scrap is the fastest-growing segment of municipal solid waste; it accounts for between 3 percent and 5 percent of incoming materials.

Electronic scrap management’s two primary processes are refurbish/reuse/resale and recycling. However, approximately 75 percent to 85 percent of waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) at the end of its first useful life is sent directly to landfill burial or incineration. Another 10 percent is stored, passed down or donated to charity, and an optimistic estimate of up to 15 percent is diverted for reuse and recycling.

Government intervention has created a framework for e-scrap management that is now being replicated—with numerous modifications—around the world. Such intervention has taken shape in the form of laws and regulations, beginning with the European Union’s WEEE Directive and subsequent amendment banning the export of WEEE to non-OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries.

In addition, the Reduction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive, implemented first in the European Union in 2003, is influencing the product design processes of OEMs. RoHS has become the de facto standard to encourage the removal of toxic materials from electrical and electronic equipment. Many of the large OEMs are taking credit for their efforts to reduce the number and quantity of toxic materials, which they balance with the needs of the customer for price/performance and reliability.

HANDLING THE STREAM

Electronics recycling processing technology has increased efficiency and capacity for some of the largest electronics recycling companies that can make the necessary capital equipment investments. The ability to separate constituents in a mixed stream into distinct classes of materials is increasing with each new generation of electrical and electronic equipment.

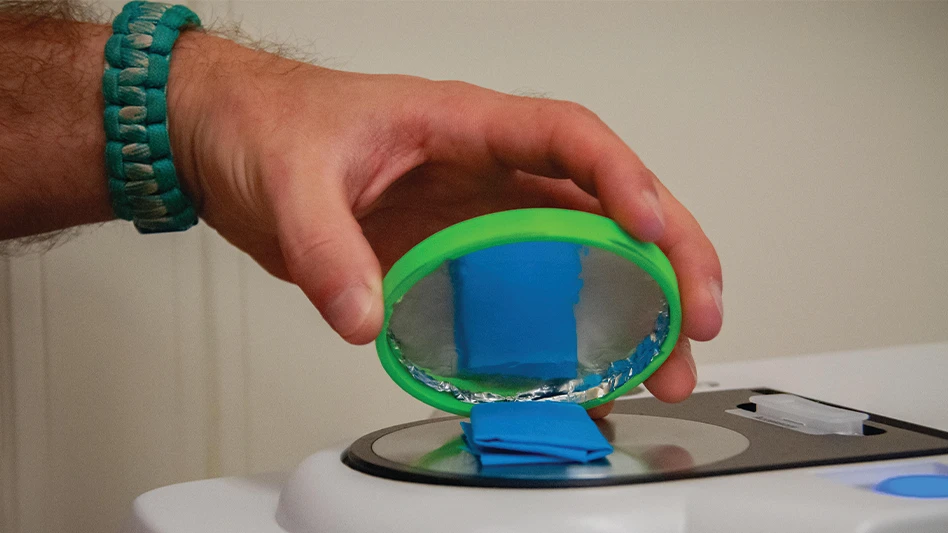

However, the first steps in the reuse/recycle system are manual. It takes people and manual dexterity to disassemble a piece of electrical or electronic equipment to extract hazardous constituents, valuable components or subassemblies prior to automated processing. The true value of electronic scrap materials sent for recycling is as feedstock for other new products or for direct reuse as recycled content in similar products.

Issues associated with the processing of electronic scrap in developing countries and the inconsistent enforcement of government-mandated requirements around the world have raised the awareness of OEMs, consumers, e-waste management companies and government agencies. The largest OEMs have had internal requirements and control systems related to government-mandated environmental programs in place for a number of years.

The risk of enforcement, bad publicity and customer reaction (with a little help from the NGOs) is far greater than the cost to handle and dispose of these industrial materials in an appropriate manner. Yet, opportunities exist for improvement throughout the reverse logistics supply chain related to audits and tracking system transparency.

Governments, particularly those in global leadership roles and those whose economies generate a significant percentage of electronic scrap, must participate in the process by supporting existing treaties, helping to develop new and better ones and taking enforcement action. The export of electronic scrap, in and of itself, is not inappropriate. It supports the closed-loop, multiple-pass processes of reuse and recycling in proximity to the demand for raw materials. The majority of new manufactured goods of all kinds are being made in developing countries because labor rates and regulations are more favorable than in other parts of the world. Raw materials for manufacturing all of these products are being delivered through a global supply chain.

This supply chain should include materials recovered from recycling operations around the globe and should benefit from the same lower labor rates.

Moreover, safe working conditions and appropriate environmental protection and disposal of residuals must meet minimum requirements for contracting for electronic scrap processing services in the developing countries.

We, as citizens of the world, are consuming ever-increasing quantities of raw materials to make new and more functional electrical and electronic equipment that must be dealt with at the end of its first, second or “nth” useful life. Appropriate recycling of obsolete electronic devices can provide an increasing percentage of that demand. The projections for electronic scrap are increasing, on average, 3 percent to 5 percent per year, with a lag time equal to the first product life cycle (1.5 to two years for handheld devices, five to seven years for PCs and TVs and a variable life cycle in the business sectors using networking and electrical control equipment).

We estimate that there will be more than 60 million tons of electronic scrap at the decision point for reuse/recycle or landfill in 2013. The recycle rate could go as high as 50 percent or more, depending on government intervention and economic incentives provided to consumers. Assuming a recovery rate of valuable materials at 45 percent of the gross quantity of electronic scrap available, approximately 14 million tons of raw materials could be available for new product manufacturing during 2013.

Purchasing power parity (PPP) will continue to favor the developed countries where the standard of living is high enough to support the purchase of new equipment on a periodic basis. In the developing countries, PPP will not support the purchase of new computer equipment. However, the availability of refurbished equipment for resale is a huge opportunity for asset management and electronic scrap management companies that focus on resale.

The barrier to entry for handheld devices is decreasing for consumers, and demand for these devices is increasing, which means more new cell phones will be sold than computers. Still, the resale market for these devices will also flourish. Consumer behavior needs to be modified via a combination of awareness, incentives and constraints to begin to change ingrained habits.

Surveys by OEMs and advocacy groups indicate a majority of consumers do not know what their options are when a piece of equipment reaches the end of its useful life. Success will be enhanced by the perceived degree of convenience in getting WEEE into the recycle processes. Money continues to be a great motivator in terms of handling electronic scrap. This factor has led to solutions in the form of landfill bans, OEMs with individual producer responsibility (IPR) requirements and advanced recycling fees (ARFs) in some locations.

This article is an executive summary of Electronics Recycling and E-Waste Issues. The full 109-page report is available from Pike Research, Boulder, Colo., at www.pikeresearch.com or by phone at (303) 997-7609.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the October 2009 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- The Scrap Show: Dhawal Shah of Metco Ventures LLP

- AEPW releases new mechanical recycling ‘playbook’

- Nucor to expand downstream products capacity

- APR launches Recycling Leadership Awards

- Private equity firm announces majority investment in Sprout

- Author predicts spike in silver’s value

- SWANA webinar focuses on Phoenix recycling collaboration

- Domestic aluminum demand up through Q3 2024