In July 2009 the Indiana General Assembly enacted the Indiana Electronic Waste Law, establishing the Indiana E-Cycle program. The purpose of the program, in part, is to reduce the

Since January 2011, Indiana households, small businesses

That same year, Oscar Winski Co., a century-old scrap metals recycler headquartered in Lafayette, Indiana, added an electronics recycling division. The 111-year-old company realized serving as a one-stop shop could pay off.

Oscar Winski has since grown its electronics recycling division from two employees to an average of 18. The division started off processing 200,000 pounds annually and now handles more than 1 million pounds per year, says Ben Evans, business development manager at Oscar Winski

“The electronics recycling division has grown exponentially over the seven-year life,” says Evans. “We’ve worked hard to reposition ourselves from base-level dismantling to reuse and refurb.”

The progress the electronics recycling segment has experienced can be credited mostly to moves the company has made over the years—literally and figuratively. In terms of mile radius related to customers served, Evans says Oscar Winski has expanded its reach from a 90-mile radius to nationwide.

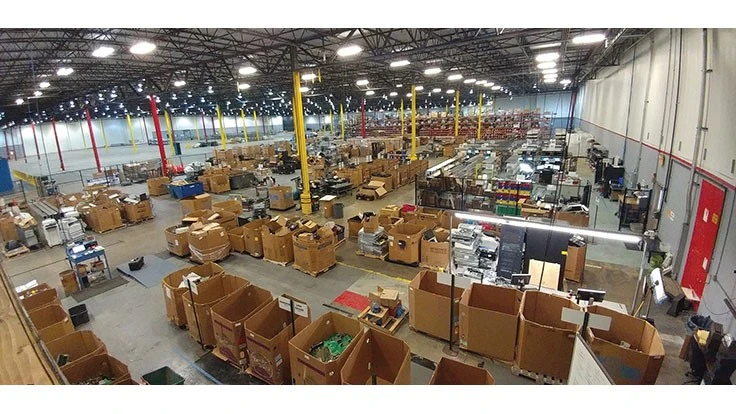

The recycler recently purchased the 160,000-square-foot Caterpillar Logistics Center in Lafayette, more than doubling Oscar’s electronics recycling and logistics capacities. Both divisions needed expansion space, Evans says. The new space met that demand and has room for growth. With multiple docks, the two divisions can work independently of each other. Evans says he anticipates the entire footprint eventually will house the company’s business.

“The old Caterpillar Logistics Center is a great fit for us. It offers space for immediate needs, and we can expand in the future,” Evans says.

The company now has more room to handle e-scrap, including nearly any old or obsolete electronic device with a cord or battery: calculators, cameras, cellphones, circuit boards, copy machines, hard drives, keyboards, DVD players, iPods, laptops, medical equipment, microwaves, printers, radios, TVs, vending machines, video game systems and wiring, among many other devices. Oscar Winski

As the first Indiana-based electronics recycler to be certified to the R2 (Responsible Recycling Practices) Standard, Evans says this allows the business to improve its processes. The R2 Standard is designed to help ensure the quality, transparency and environmental and social responsibility of electronics recycling facilities around the world. More than 750 R2-certified facilities are operating in 30 countries, according to SERI, the housing body and American National Standards Institute- (ANSI-) accredited standards development organization for the standard.

In addition to this certification, Oscar Winski eRecycling is registered with the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM), which is required under Indiana’s Electronics Waste Management rules.

“Our goal has always been to stay landfill-free,” says Evans. “The R2 protocols ensure we give the best service for your needs. More and more, it’s important to organizations to show their owners and taxpayers that they’re conscious of how they’re handling their e-waste.”

Precious methods

Evans says Oscar Winski

“We’re capable of different types of data destruction, but as our flow changes over time, our data destruction procedures change over time. We’re still coming up with more effective and strategic ways to improve,” Evans says.

He adds, “Our process for e-waste varies greatly based on the type and age of the material being processed.”

The

Depending on the sector and media, Evans says performing destruction services on-site varies. The company can magnetically wipe hard drives, for example, in front of a client’s workers, ensuring data never leave the building through in-house data destruction. The demand for this service has grown over the years, he says.

“It’s preferential and it really does vary based on what sector they’re in,” Evans says of on-site data destruction. “Some demand it, some didn’t even know we did it until we said we offer it.”

The company uses downstream vendors for recovering precious metals. While an active area, Evans says the presence of precious metals in e-scrap has dwindled over time.

“Many people believe electronics have many precious metals; yes, in the ’90s, but not so much anymore,” Evans says.

Although the amount of precious metals contained within e-scrap has lightened like the devices themselves have in weight, a considerable monetary amount of metals still heads to landfills.

A report released in December 2017 shows that $55 billion worth of recoverable materials were left in e-scrap in 2016. The joint study, “The Global E-Waste Monitor 2017,” released by the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA), Vienna; United Nations University (UNU), Tokyo; and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Geneva, reports that 44.7 million metric tons of e-scrap were generated globally in 2016, an increase of 3.3 million metric tons, or 8 percent, from 2014.

Of the total e-scrap generated in 2016, 20 percent is documented as having been collected and recycled, according to the report. This is “despite rich deposits of gold, silver, copper, platinum, palladium and other high-value recoverable materials. The conservatively estimated value of recoverable materials in last year’s e-waste was ... more than the 2016 gross domestic product (GDP) of most countries in the world,” ISWA indicates in a news release.

The report foresees a further 17 percent increase in disposal—to 52.2 million metric tons of obsolete electronics by 2021—the fastest growing part of the world’s household discarded materials stream.

It is this fast-growing and constantly changing aspect of electronics recycling that Evans says is a challenge as well as a window of opportunity for recyclers.

Preparing for what’s ahead

Electronics recycling provides a daily challenge in relation to product design, innovation and changing flows of material, Evans says. He points to the ever-changing nature of the sector as necessitating awareness of what is new and what is old, referring to it as “hyperdynamic.”

Evans adds, “Electronics recycling today will look very different than the electronics recycling of tomorrow. In general, our challenges are keeping up. Keeping up with every sector we deal with—residential, schools, etc.—keeping up with their needs.”

Keeping up with the pace of change is critical. The electronics recycling industry has three to five years to prepare for end-of-life electronics, Evans says.

He adds that with technology finding its way into more homes and clothing, among other products, the

“With OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) incorporating cloud connectivity and local storage, we see the need to keep very

In addition, infrastructure for electronics recycling is still in its infancy. “It’s very different than residential and trash, where collection infrastructure exists,” Evans says. “It doesn’t exist [for electronics recycling] in many local areas.”

Despite these tests, Evans says Oscar Winski’s

“We have grown significantly and focused moving up the value chain and moving more resources to reuse and refurb markets,” Evans says. “We are optimistic.”

Explore the April 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Nucor receives West Virginia funding assist

- Ferrous market ends 2024 in familiar rut

- Aqua Metals secures $1.5M loan, reports operational strides

- AF&PA urges veto of NY bill

- Aluminum Association includes recycling among 2025 policy priorities

- AISI applauds waterways spending bill

- Lux Research questions hydrogen’s transportation role

- Sonoco selling thermoformed, flexible packaging business to Toppan for $1.8B