China’s era of sustained industrial growth began shortly after then-Chairman Deng Xiaoping began introducing economic reforms in the early and mid-1980s. By the 1990s, China’s industrial growth entailed, in part, importing massive amounts of secondary commodities, including scrap metal, paper

Scrap processors and traders who have been in the business for 20 years, and therefore can be considered industry veterans, have only known a global market where Chinese companies were the leading overseas buyers. For many of these same traders and processors, making freight arrangements often

China’s seemingly “no-strings-attached” attitude toward imported scrap changed perceptibly in 2013 with Operation Green Fence. That action, led by a coalition of Chinese central government agencies, was designed to enforce frequently ignored quality standards for imported materials, with a sharp focus on mixed plastics and mixed paper.

In 2017, the National Sword campaign and several follow-up actions brought further restrictions, this time including contaminant limits that are tougher than the global standards and outright bans on certain scrap materials.

For traders and processors of plastic scrap, the landscape appears to have changed abruptly and permanently. While trade negotiators from North America and Europe are questioning China’s newly declared restrictions, the Chinese government has positioned the scrap material bans as an internal environmental matter.

In 2018 and beyond, recyclers undoubtedly will watch for any changes on the policy front. At the same time, however, they also are researching and making capital investments designed to adjust to the new reality, which involves finding new ways to prepare certain grades of scrap.

Targeting plastic scrap

Operation Green Fence in 2013 caused some discomfort and changes to the scrap metal sector, but the major impact occurred within the material recovery facility (MRF) and plastics recycling sectors.

For more than a decade, many MRF operators had become accustomed to allowing outthrow and contaminant levels on export shipments to drift upward, as Chinese buyers desperate for sufficient volume offered relatively few quality complaints.

Changing attitudes in China perhaps can be ascribed partially to protectionism (and stimulating China’s domestic recycling activities), but the issue as China’s government describes it is laden with references to “foreign garbage,” usually pointing to substandard mixed paper and mixed plastic shipments.

Plastic scrap, in particular, has been demonized, in part by a 2016 documentary called “Plastic China” that reportedly enjoyed wide viewership in China, perhaps even at the highest levels of government.

The 82-minute documentary focuses on one woman and her 11-year-old daughter, who work at and live next to a sizable plastic scrap sorting operation where “foreign garbage” (as referred to by the documentarians) is sorted by hand.

Media reports in China indicate the documentary struck a nerve in the nation, perhaps all the way up to the level of current President Xi Jinping. Without question, as China introduced its new scrap import restrictions in 2017, in the plastics sector the restrictions were harsh and immediate.

By the spring of 2017, thousands of containers of plastic scrap were being refused entry into Chinese ports. Some 5,000 containers reportedly were stuck in drayage in Hong Kong alone by April 2017.

John Paul Mackens of freight forwarder Kuehne + Nagel, who spoke at the 2017 Paper & Plastics Recycling Conference Europe in the fall, said Europe sent 89 percent of its outbound plastic scrap to Chinese ports in 2016. In September 2017, Mackens said, just 46 percent went to Chinese ports, with Malaysia receiving 12.6 percent, Hong Kong receiving 10.7 percent and Vietnam 9.5 percent.

As of early 2018, plastic scrap stockpiles reportedly are building at MRFs throughout the United States.

Of the two dozen scrap materials that faced outright import prohibitions in China, eight were forms of plastic scrap and just one was a mixed paper grade. (The others were metallic slags and residues and used clothing or textile shipments.)

For MRF operators and other paper and plastics recyclers, the needed adjustments have been swift and likely are permanent (in the plastics sector). In the current situation, it can be hard to spot the opportunities within the challenge.

“We have scaled down plastics we take in,” says Kathy

Shannon Dwire, president of Millennium Recycling Inc., Sioux Falls, South Dakota, says, “I think it naturally makes you more respectful of your domestic partners, and you work harder to strengthen those relationships. You watch quality and solidify your commitments to make sure you have a product that is wanted and even preferred over other suppliers.”

In the wake of Operation Green Fence in 2013, technology suppliers to the MRF sector enjoyed a boom in new automated and optical sorting investments. While such suppliers are privately owned and do not report sales figures, this decade’s flurry of sales and installation announcements points to ongoing investments by MRF owners.

Municipal collection and hauling contracts on the MRF side and industrial service arrangements on the plastics side can make it difficult for recyclers in the U.S. to simply refuse newly restricted materials. The sustainability movement among manufacturers and consumer products companies

However, with the North American recycling sector largely

“For too long we depended on shipping to China. It was shortsighted on our part and on the part of the whole recycling industry.” – Sunil Bagaria, GDB International

Volumetric decisions

Among the truisms espoused by

For recyclers examining the post-China-restrictions landscape, that means investing in processing capacity not merely because

In the MRF sector, suppliers of screening and sorting equipment and systems have announced a steady succession of sales to recycling companies that, because of contract commitments, will continue to accept a high volume of material and must then sort it thoroughly.

Ron Sherga, CEO of Arlington, Texas-based EcoStrate, says his company is among those that could be poised to benefit from China’s import restrictions. EcoStrate, the 2017 Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) Design for Recycling award winner, takes in mixed and traditionally “difficult-to-recycle” plastic scrap and converts it into street signs, park benches

As of early 2018, Sherga says he is enjoying access to additional material, which he had predicted would be the case. “EcoStrate has always expected a reshoring shift, and our EcoStrate model focused on pursuing large markets with sustainable profit margins without material subsidies. Our manufacturing capabilities are already falling far short of the demands we are seeing. This China effect has added to that demand and interest.”

While he is glad EcoStrate is benefitting from the changes, Sherga indicates he would rather see a larger trend of America finding additional ways to process and consume its own scrap.

“I think it’s a wake-up call that we must have facilities that make things capable of using these materials to succeed,” he says. “Export plays a role and always will, but many companies got lazy and still lack resources or don’t fully understand scrap markets, and their struggles will get worse.”

Sunil Bagaria, president of GDB International Inc., New Brunswick, New Jersey, says companies, particularly those handling plastics, have become overly reliant on China. “For too long we depended on shipping to China,” Bagaria says. “It was shortsighted on our part and on the part of the whole recycling industry.”

With the advent of China’s ban on certain types of plastic scrap, he predicts, “Each country will be responsible for their own collection and recycling.” The only enduring solution to the situation China has created, Bagaria says, is developing domestic reprocessing capacity for recovered plastics.

“I think it’s a wake-up call that we must have facilities that make things capable of using these materials to succeed.” – Ron Sherga, EcoStrate

Making the investment

Since 1993, GDB International has been collecting, sorting and trading plastic scrap, including polyethylene (PE) film, from

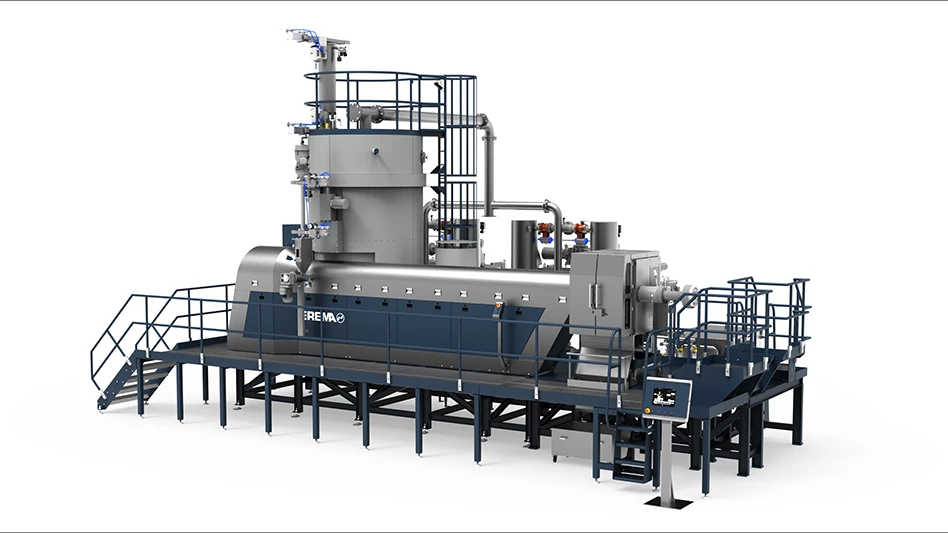

The company’s New Brunswick plant measures 110,000 square feet. Approximately 60,000 square feet will be used for pellet production, which will be divided among four lines consisting of metal detectors, inline densifiers, vented extruders equipped with automatic screen changers and underwater pelletizers, Bagaria says.

The first line, capable of producing 1,300 pounds per hour, is up and running. The second, somewhat larger line is being installed now and is expected to begin operation in June, Bagaria says. The third and fourth lines, each rated to produce 3,000 pounds per hour, will be installed later this year.

“By the end of 2018, we should be making 2.2 million pounds of plastic pellets per month,” Bagaria says, adding that it should reach full production by the early part of 2019.

GDB International plans to sell its finished pellets to the domestic and export markets. It is targeting manufacturers of garbage bags and other plastic film products as well as the pipe and irrigation sectors.

The company wants to create more value for its suppliers of plastic film scrap—largely grocery stores and retailers—by recycling plastic film in the U.S., Bagaria says.

“There is more value to be realized and shared,” he continues. “We will help them see that recycling can pay. It has to make economic sense; only then will the recycling story be successful.”

Chinese companies also are adding U.S. operations in response to China’s new scrap import policies.

Once such company is Shanghai-based Roy Tech Environ Inc., which has announced plans to open a plastics recycling plant in Grant, Alabama. The company says it needs to build production capacity in the United States to guarantee its factories in China will have access to a sufficient amount of recycled plastic.

The company’s U.S. plant will shred, grind and pelletize postindustrial plastic scrap, primarily HDPE, polypropylene (PP) and polycarbonate (PC), that will come largely from its existing customers. Roy Tech Environ currently has a branch trading office in Huntsville, Alabama, about 30 miles away from Grant. The company established that location more than three years ago to be close to major auto production facilities.

Roy Tech Environ CEO Lingli Zhang says the new production facility will install grinders and shredders for five production lines in Phase I of the build-out. In Phase II, it will install pelletizing equipment.

The plant will begin operating this summer, she

North America’s MRF operators and traders of plastic scrap likely are watching to see if a

EcoStrate, 646-715-6894, www.ecostrate.net; GDB International, 732-246-3001, www.gdbinternational.com; Millennium Recycling, 605-336-1744, www.millenniumrecycling.com; Roy Tech Environ, 626-632-5922; Texas Recycling, 214-357-0262, www.texasrecycling.com

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the May 2018 Plastics Recycling Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- European project yields recycled-content ABS

- ICM to host co-located events in Shanghai

- Astera runs into NIMBY concerns in Colorado

- ReMA opposes European efforts seeking export restrictions for recyclables

- Fresh Perspective: Raj Bagaria

- Saica announces plans for second US site

- Update: Novelis produces first aluminum coil made fully from recycled end-of-life automotive scrap

- Aimplas doubles online course offerings