Among the misfortunes that can strike a baling operation is the phenomenon known as bridging. While "building a bridge" is often used as a positive metaphor when it comes to relationships and planning for the future, the bridges found in balers are entirely unwelcome.

Most sources contacted for this story agreed that production-halting bridging problems occur at the entrance to the charge box when a piece of oversized material (most often a large cardboard box) is unable to enter because it is too wide or has fallen at an awkward angle, clogging the entrace to the charge box.

| Tale of the Tapes |

|

Business owners in the recycling industry have access to a series of new safety videos being produced by the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries Inc. (ISRI) Washington. The ISRI videos on baling equipment, conveyors, shearing equipment, truck rollovers and other topics use alarming graphic images and recountings of actual incidents to jar viewers into understanding the dangers they face every day if they don’t pay attention to the equipment and conditions around them. Whether viewed by new hires or veteran employees, these videos can serve to jolt workers and managers alike into realizing that the dangers are real for those employees who are careless in the scrap processing work environment. ISRI member companies can purchase most of the videos in the $50 to $75 price range, while nonmembers may have to pay double that. Many of the videos are available in both English and Spanish. Recyclers interested in the videos can earn more about the series by visiting the Safety Videos section of the association’s on-line bookstore at www.isri.org (also http://isri.safeshopper.com) or by calling ISRI’s national office at (202) 737-1770. |

"Think of it as if you are filling a penny wrapper," says Ken Korney, director of worldwide sales for International Baler Corp. (IBC), Jacksonville, Fla. "One penny that is lodged in there sideways stops you from filling up the rest of that role of pennies."

OUNCE OF PREVENTION. Baler designers and manufacturers can play a role in alleviating bridging problems, but so can operators and supervisors at recycling plants.

"If you’re at a recycling facility with large amounts of old corrugated containers (OCC), make sure you don’t lump-feed material and overload the conveyor," says Jim Jagou, vice president-sales with Harris Waste Management Group Inc., Peachtree City, Ga. "The operator should try to keep a smooth, even flow of material going."

Even material flow increases the likelihood that an employee will spot a problem container before bridging occurs.

Appliance and Gaylord boxes are frequent culprits, though cores or rolls and smaller retail bales that are being re-baled were also mentioned.

"Loader operators should absolutely be on the lookout" for such materials says Richard Harris, sales director of the Macpresse line of balers for Sierra International Machinery Inc., Bakersfield, Calif.

"It’s critical to instruct people how to feed the conveyor," says Korney. "With an in-ground conveyor feeding an auto-tie system, material needs to be fed in a uniform way. Don’t push a 6- or 7-foot mound of corrugated onto the conveyor."

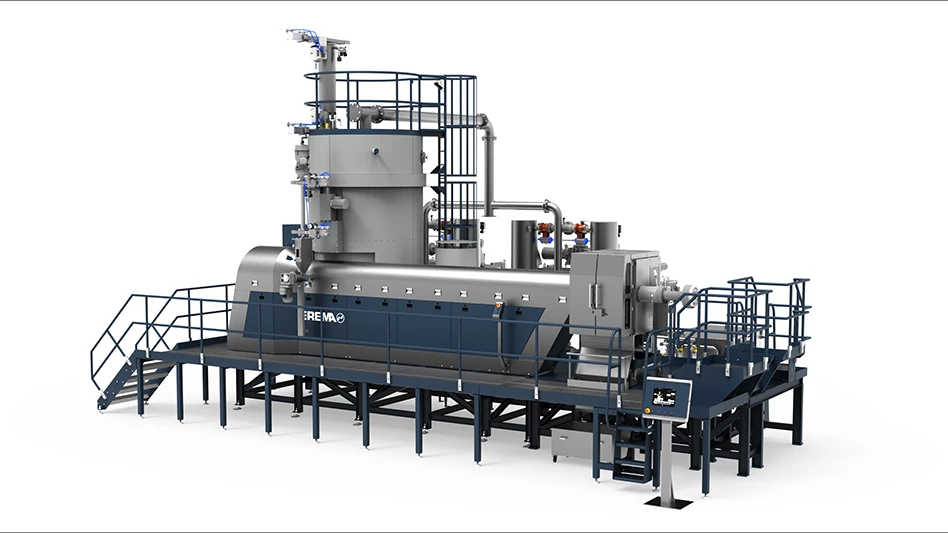

BRIDGE-BUSTING DESIGNS. Baler manufacturers have also put thought and talent into designing balers that are less likely to create bridging problems.

The Macpresse models offered by Sierra provide what Harris calls a "nose-over" design that uses gravity to help material to cascade with the heavier (and presumably narrower) end falling first into the charge box. Combined with the appropriate incline angles and spacing between the conveyor and the hopper, this will "allow the material to slide into the hopper, eliminating the likelihood of bridging," Sierra’s Harris says.

IBC’s Korney recommends recyclers make sure the unit they choose has a charge box that is wide enough.

Fred Johnson of IPS Balers Inc., Baxley, Ga., says the company’s hinged sidewall models, which temporarily open the charge box up "to 55 or 72 inches wide and eliminate that hourglass shape that can cause bridging," provide a potential solution. "The width of the charge box is the critical dimension when you’re looking at baling OCC."

Jagou stresses the importance of "sizing the right machine for the application. For recyclers baling a lot of OCC, they should always try to get the model with the widest charge box."

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

SAFETY FIRST. Any time bridging occurs, proceeding safely to fix the problem is critical.

Production headaches caused by frequent bridging can add up. "It might take anywhere from five to 15 minutes to fix a bridging problem," says Korney, who notes that an individual using a broom handle or other ramming device is still the most common method to clear the jam.

Although simple, this technique is also potentially the most dangerous. "You absolutely have to go through the lock-out tag-out procedure," Jagou says.

Despite the best efforts of recycling companies, equipment manufacturers and the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries Inc. (ISRI), those procedures are not always followed.

Manufacturers have responded by including automatic eyes and other "tripping" devices that automatically shut down a baler and the attached conveyors when certain motions are detected.

The author is editor of Recycling Today and can be contacted via e-mail at btaylor@RecyclingToday.com.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the February 2004 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- LumiCup offers single-use plastic alternative

- European project yields recycled-content ABS

- ICM to host colocated events in Shanghai

- Astera runs into NIMBY concerns in Colorado

- ReMA opposes European efforts seeking export restrictions for recyclables

- Fresh Perspective: Raj Bagaria

- Saica announces plans for second US site

- Update: Novelis produces first aluminum coil made fully from recycled end-of-life automotive scrap