Steel mills have grown accustomed to paying large amounts for ferrous scrap, with mill buyers having a bigger incentive than ever to insist on receiving quality shipments.

Industry pricing shows that mills pay more per ton for prompt grades that can meet melt shop chemistry requirements.

But in the United States, prompt scrap generation has not been soaring for the past three years, meaning mill buyers with stringent chemistry requirements are seeking other types of feedstock.

Among the grades that some mills are tapping into is what the RMDAS survey from Pittsburgh-based Management Science Associates Inc. (MSA) calls No. 1 shredded scrap, defined as having .17 percent or less copper.

The Local News

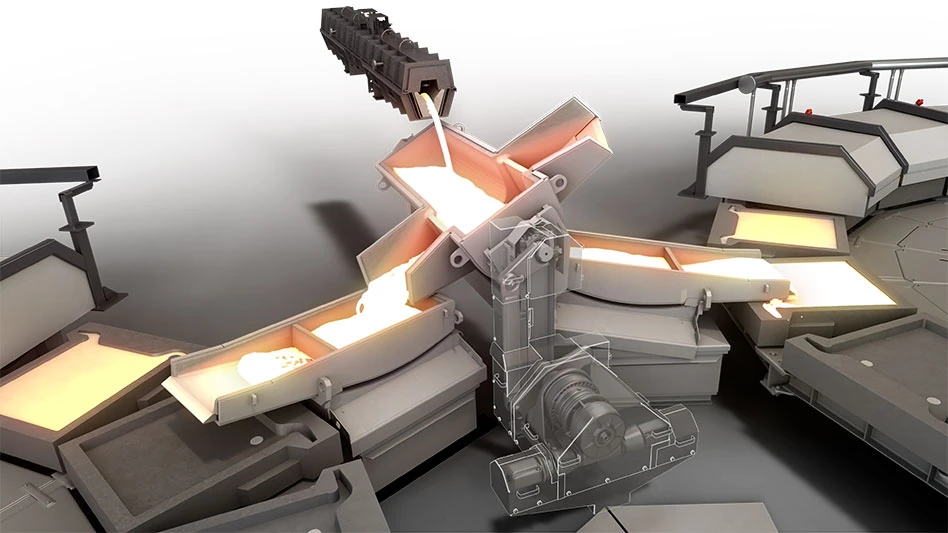

Several steps can go into producing a grade of shredded ferrous scrap that keeps the content of residual copper (and other “tramp elements”) at a low enough threshold to charge a premium.

Whether it is worthwhile to invest the time and money to take these steps, however, can first depend upon a shredder operator’s mill buying customers.

“The chemistry you’re looking for is related to that mill’s supply base and sourcing strategy,” says Dan Pflaum, president of Gamma-Tech (http://gammatech.us), Dayton, Ky. Gamma-Tech makes and installs bulk analyzers that determine the chemistry of the shredded material passing beneath it on a conveyor.

Gamma-Tech’s analyzer allows shredder operators to show the precise levels of four elements considered unwelcome at most carbon steel mill melt shops—copper, nickel, chrome and manganese.

“We’re not sampling,” Pflaum says of the Gamma-Tech process. “We’re truly measuring the depth of the material on a composite basis, and the measurement is taken as real-time process control information. The speed of belt does not need to be slowed down for the bulk analyzer. We’re installed on shredder systems producing from 80 to 400 tons per hour of material.”

Shredding plant operators can all benefit by knowing the specific chemistry of their product, says Pflaum, but he says the payback value can be most apparent to operators who sell to nearby mills seeking low-copper content feedstock.

“Copper is usually the center of attention, but we also have customers who are seeking very low levels of chrome or manganese content,” says Pflaum.

Factors influencing the demand for premium ferrous shred in a market can include the type of steel being produced at the nearest electric arc furnace (EAF) mill and the availability of prompt scrap in a mill’s region.

“If a mill is making rebar or light structural steel, they’re not likely to be as concerned about the specific chemistry,” says Pflaum. “But if it’s producing flat-rolled steel, wire rod or SBQ (special bar quality) steel, then the chemistry is of great importance.”

Such mills, historically, have been buyers of prompt industrial grades of ferrous scrap. “If they can get readily available, reasonably priced prompt scrap, then seeking out clean shredded scrap is not as important,” says Pflaum. “But if the mill is in a part of the country where there is less prompt scrap, or the prompt scrap is coming from your own mill, which is already near the tolerance threshold, then [buying premium shred] is more of a factor,” he adds.

That task is left to shredder operators and several manufacturers of magnetic and sensor-based equipment designed to identify and separate nonferrous metals in the post-shredder stream.

Tim Shuttleworth, president and CEO of Eriez (www.eriez.com), Erie, Pa., has been involved in that company’s research and development of new products being offered for this application.

His customers, like Pflaum’s, are telling him they see a return-on-investment value in producing low-copper content grades. “If they’re able to produce something at a specific copper level, it will increase the market value of the scrap and also make it cost-effective to market that scrap to a wider geographic region,” says Shuttleworth.

A combination of factors may be teaming up to heighten the interest in No. 1 shredded scrap or other variations of low copper-content ferrous shred at both steel mills and shredding plants.

Gradual Erosion

EAF steel mills that seek out prompt scrap as their preferred feedstock have been concerned about tight supply of prompt grades for a number of years.

Several trends are conspiring to make the grade increasingly scarce in the United States, including the large scale shift in manufacturing plant locations from North America to Asia; the ongoing focus on improved manufacturing methods at remaining plants to use materials wisely (and thus generate less scrap); and the greater market share for EAF steel vs. basic oxygen steelmaking.

That last factor means that even the prompt scrap that is generated in many regions is less “pure” than it would be if it came from an integrated plant.

“The quality of prime scrap is deteriorating,” states Pflaum. “Twenty years ago, the copper level in prime scrap may have been .03 or .04 percent. Now, depending on the geographic region, the amount of copper in prime scrap might be .06 to as high as .10 percent.”

What that means for melt shop managers at carbon steel EAF mills is that if the prime scrap they are buying already contains that much copper, then the additional scrap they purchase—including shredded grades—will have to contain less copper than in the past.

This variable compounds the woes of melt shop managers who compete for the limited amount of prime scrap available because of those first two factors (less manufacturing and less intense scrap generation at remaining factories).

“What we have in this country, though, is an abundance of obsolete scrap,” says Pflaum. “As a shredder operator or mill manager, you can either use technology to manage and control that or face some rough going.”

Blending And Cleaning

The growing market for cleaner ferrous shred has, in some cases, caused EAF melt shop managers, mill buyers and their scrap suppliers to work in closer cooperation to produce such a grade.

Scrap processors point out that the best way for mills to ensure they have an adequate supply of clean ferrous shred is to pay a premium for the grade.

In some cases, this simple application of market forces has made a difference. One recycler, who preferred not to be identified, segregates and shreds separately the ferrous scrap generated at the factory of a fairly large-scale local generator. For this clean shredded product with a predictable low-copper level, the recycler may fetch a premium of as much as $100 per ton from a regional steel mill.

That example involves an extreme case of carefully selecting feedstock and an extreme premium that is far from typical.

MSA collects and aggregates mill buying transaction information as part of its

service.

The company does not disclose individual transaction information, but does record and distribute average pricing during given buying periods. Regarding the premium scrap recyclers can receive for producing a No. 1 shredded product (below .17 percent copper), the company says, “Some months there may be little difference ($5 per ton) and other months a greater difference ($25 to $30 per ton). However, a general estimate of the average price difference between No. 1 shredded and No. 2 shredded scrap would be $10 to $15 per ton.”

Whether that spread is enough of an incentive for shredder operators to produce the No. 1 shredded grade can be a source of discussion between recyclers, mill buyers and equipment makers.

“We’ve never run a shredder,” Pflaum says of Gamma-Tech as a way of offering a disclaimer about how a scrap recycler approaches this equation. “But it’s a process with a lot of variables—the speed of the shredder, the mill and downstream system setup, picking operations, the feedstock—all of those variables need to be monitored and controlled.”

On the feedstock side, Pflaum states, “The industry myth that making low-copper scrap means completely changing your feedstock is false. We have customers making small changes to feedstock that are more related to keeping out the obvious offenders—things such as vending machines with wiring and tubing or demolition scrap with a lot of rebar or wire or conduit. But that is a small fraction of their overall feedstock.”

Attention is largely focused on downstream systems. As a provider of equipment for such systems, Shuttleworth says Eriez will continue to introduce new products and combinations of products designed to be deployed as a process to further separate nonferrous from ferrous scrap in the post-shredder stream.

As technology evolves, scrap recyclers likely will have a wider array of technological solutions to consider. Also, how many hand pickers to keep on the line and where to put them for maximum effectiveness remains a consideration.

“What we have found is that with accurate, science-based information, shredder operators can make good decisions to make the appropriate material for their market region,” says Pflaum.

Steel mill buyers will play a role in that decision through their willingness to pay a premium for lower-copper-content ferrous shred or for shred that comes with guaranteed (bulk analyzed) chemistry.

“I think there is a recognition in the marketplace among metallurgists and steelmakers that nobody likes to guess what they’re buying,” says Pflaum. “There is a value in knowing the metallurgical specification to the key raw material in their process, and there does need to be a recognition and an incentive.”

WANT MORE?

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the January 2011 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta

- MTM Critical Metals secures supply agreement with Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations