Electronics recycling continues to mean different things to different people, with some putting a heavier emphasis on reconditioning and re-use while others are now focusing on recovering metals, plastic and other secondary raw materials.

With a recent major investment, Gold Circuit Inc., Chandler, Ariz., has joined a small roster of companies that can offer comprehensive information security, reconditioning and product recycling and disposal services.

The company’s background in asset recovery has linked it to a considerable corporate base of customers with obsolete electronic equipment. A second wave of material may well come from the residential stream in California, where electronic equipment is increasingly being turned away at landfills.

Jim Greenberg, founder and president of Gold Circuit, Inc.

BEYOND CIRCUIT BOARDS

Entire states and cities can trace their origins back to a regional gold rush, and several recycling companies were similarly rooted in the hunt for gold.

"When we first started 11 years ago, our efforts went into reclaiming gold from electronic parts and circuit boards," says Jim Greenberg, president of Gold Circuit Inc.

But the computer reconditioning and resale market soon found Greenberg and his fledgling business. "Within six months, used computer dealers came in and wanted to buy entire units, so we quickly switched over to a broader business model."

The company started with two people and 1,000 square feet of space, notes Greenberg. As operations grew more diverse, employees and space were added, and the number of potential directions the company could take multiplied.

Adding to the mix of services were requests from corporate clients, such as financial institutions, who wanted to ensure that data was destroyed. "There’s always been a certain amount of disassembly, but we also clean hard drives or use certified software technicians to remove software imprints on telecommunications equipment," says Greenberg.

The greatest change to Gold Circuit’s business, however, is coming from the disposal side of the equation. "There is a big issue with computer monitors and televisions in particular becoming hazardous wastes," says Greenberg. The recent disclosure of unsafe disassembly of such pieces of equipment in China has added to the need to provide a different recycling or disposal method, he notes.

"There aren’t a lot of alternatives," says Greenberg regarding the end-of-life handling of monitors and televisions, often referred to as CRTs because of the cathode ray tubes found within. "Every time you track down the alternatives, you find they are still going somewhere overseas."

Nearly a year ago, Greenberg made the decision to build a plant that would process CRTs and other obsolete electronic equipment by shredding it and separating out the secondary commodities.

|

KEEPING THE RECORD STRAIGHT |

|

The nature of electronic scrap recycling is such that processing it and finding end markets is not the entire story. Documentation and proof of recycling are needed by many former equipment owners, presenting an added responsibility. Gold Circuit has experience in providing this type of service, such as proof that hard drives have been wiped, says project manager Harry Strachan, and the recycling company is applying much of this experience to certifying its equipment destruction capabilities in Casa Grande. In the case of some government agencies and corporations, personnel will be assigned to watch the equipment as it goes through the shredder. "Others get a certificate of destruction," says Strachan. "It states that we have destroyed their material in accordance with all federal, state and county environmental regulations." To address any concerns regarding the disposition of the leaded glass from the CRTs, Strachan says that all customers will be provided with copies of the environmental permits that are held by the lead recycling facility consuming the glass, including such information as their ISO 9002, ISO 14000 and RCRA (Resource Conversation Recovery Act) documents. |

DEALING WITH THE UNWANTED

Gold Circuit turned to RRT Design and Construction, Melville, N.Y., to help it build a plant in Casa Grande, Ariz., that features the shredding and sorting equipment needed to safely and efficiently handle CRT scrap.

The Casa Grande plant is being operated in addition to the company’s headquarters office and plant in Chandler, where administrative, reconditioning and asset recovery operations will continue to take place.

"The Casa Grande plant was designed with a primary emphasis toward CRT monitors and televisions," says RRT president Nat Egosi, noting that this distinguishes it from other electronics recycling facilities that have been set up in other parts of the country.

The distinction spurred several design innovations both in terms of downsizing and separating materials and in making sure potentially harmful dusts and toxins are not released into the surrounding workplace.

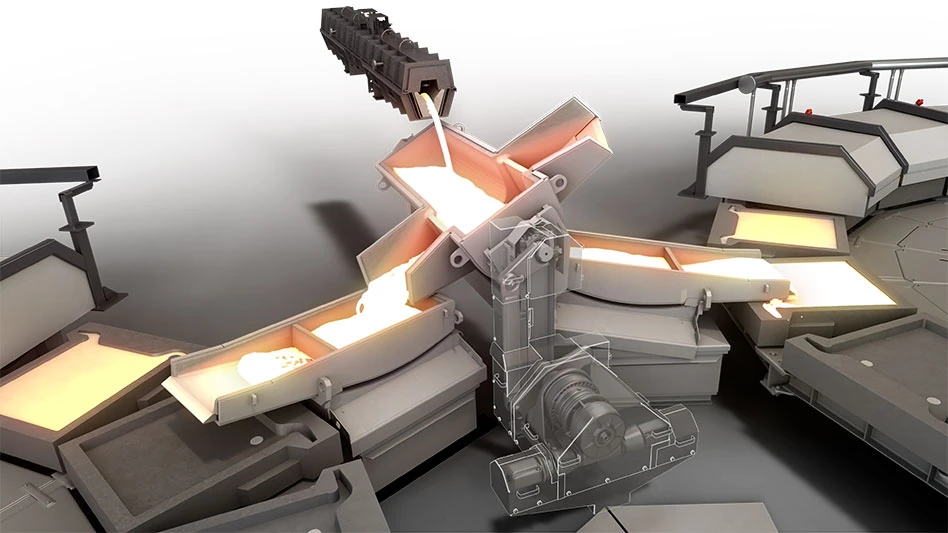

On the processing side, the E-Vantage Separator System has been trademarked by RRT and its supplying equipment companies, SSI Shredding Systems Inc. of Wilsonville, Ore., and Andela Products Ltd. of Richfield Springs, N.Y.

"SSI’s shredder is designed not only to reduce electronic scrap, but also to liberate materials from each other, such as plastic from attached metal and glass," says Egosi.

The Andela Pulverizer is used to separate out the leaded glass portion of the stream. Calling the machine a "flexible impactor," Egosi says of it, "The unique feature of the Pulverizer is that while pulverizing the glass, it does not alter the size or shape of the plastic or metal."

The shredders, combined with a series of screens and magnetic devices, produce a variety of secondary commodity streams that are shipped to a number of different consuming markets.

On the environmental side, the entire system is enclosed, says Egosi. "Once scrap enters the machine, it is completely enclosed until it comes out of the system. It is serviced by dust collection systems and a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filter," says Egosi, referring to the type of filter used in high-tech "clean rooms."

The other environmental consideration, notes Egosi, is "after the material is separated, where does it go in terms of end markets? The glass goes to lead smelters that are accustomed to handling lead, the ferrous scrap goes to its traditional end markets while the mixed nonferrous goes to media separation facilities that also are accustomed to handling diverse materials, producing a clean, consumable end product and properly disposing of any problem materials."

Although the plant has been designed with monitors in mind, the material mix could eventually change. Greenberg, though, sees CRTs as providing the initial influx of material. "I think at first we’ll see mostly terminals and monitors; this is where the problem is. People want those out of their warehouses. This includes recycling companies that may already have collected them from cities. We may work with some municipalities and not charge them for monitors versus other equipment."

Egosi says the plant is prepared to handle whatever electronic scrap may come its way. "We’ve supplied an automated system that will allow Gold Circuit to recycle all types of electronic scrap without distinguishing between them, and then to separate and create materials they can market."

The automation of the plant yields both safety advantages and allows for a processing volume that makes it efficient. "There has been no automated system that can recycle these CRTs," says Egosi. "But with our system, you can handle 600 or 700 monitors per hour. Many computer recyclers are dismantling monitors by hand and only doing that many per day, at best. The future of manual dismantling is questionable, unless the labor is free, and even then you have worker health challenges."

| THE CASA GRANDE CROSSROADS |

Although its historic home is in the Phoenix area, Gold Circuit Inc. chose Casa Grande, Ariz., as the site of its plant for the key reason of logistics. The mid-sized city is located at the crossroads of Interstates 8 and 10. "We’re on I-8, which goes to San Diego, and I-10, which goes to Los Angeles, Phoenix and Tucson," says Gold Circuit’s Harry Strachan. Gold Circuit California customers can thus find low freight costs per truckload from San Diego and Los Angeles. "We get materials at the lowest cost transportation rates compared to anybody else serving those markets," notes Strachan. If the company needed confirmation that its choice of location was a wise one, it can find it in the thinking of one of the nation’s largest retailers (one highly regarded as the foremost logistics experts in America). "This company is opening a distribution center just a half-mile away, and they probably spent quite a bit to make that site determination," says Strachan. "We feel pretty sure we’re in the right spot." |

RETURN ON INVESTMENT

In addition to the Casa Grande plant being an experiment in its processing system, there is also an element of experimentation in terms of its return on investment.

"It’s always risky any time you expand your business," says Greenberg. "We think the Casa Grande investment is worth it because of the number of customers who want CRTs handled properly. Other risks have worked out for us because we went about things the right way."

Gold Circuit will derive income from both tipping fees and from marketable commodities produced at its Casa Grande plant. "Initially, we’re charging customers between 18 and 24 cents per pound to send material to the Casa Grande plant," says Harry Strachan, who is project manager at the facility.

"We’ve set our prices to be very reasonable," says Greenberg. "We want the business right off the bat, for one reason. It will also make it affordable for municipalities and solid waste and recycling districts who collect material."

Securing enough material to keep the Casa Grande plant running near or at its 25,000-pounds-per-hour processing capacity (roughly equivalent to 800 monitors per hour) will be a key mission for Strachan, Greenberg and other Gold Circuit employees.

"Right now our clientele is largely corporate," says Greenberg. "Municipalities are interested, but they’re trying to figure out their budgets and come up with programs that will work."

But the material that could come from municipal collections in California alone (a state that is banning CRT disposal in landfills) could ultimately be significant. "A small city in California ran a three-day collection program that generated 400 tons of material in those three days," says Greenberg. "These are problems everybody has."

Jurisdictions in California had been accustomed to working with export brokers, but this practice has fallen out of favor since the disclosure of unsafe recycling practices in California stung a number of public agencies in that state. (See the June 2002 Recycling Today, "Searching for Solutions," pg. 56, and "Setting a Higher Standard," pg. 64.)

In California, disposal is not an option, and Greenberg notes that fines have been levied against public agencies and corporations whose CRTs are discovered entering a landfill. "Some California companies have been fined up to $1.2 million," says Greenberg. "So in comparison, companies love the rates we’re charging," he adds.

Recyclers in other segments are well aware of the fickle nature of the secondary commodity markets. That is one reason why Greenberg and Strachan are not relying too heavily on raw material sales when making income forecasts.

BRINGING IT TOGETHER

One of the major challenges for Gold Circuit will be the widespread dispersal of electronic scrap in virtually every household and business in the U.S.

Unlike recyclers of some materials, who can concentrate on key generators, Gold Circuit will be working with a mixed bag of large generators (major corporations and government agencies) and one and two-unit generators.

The company already has a decent handle on the large generators, as exemplified by Strachan’s assessment that 90 percent of the current mix of incoming electronic scrap will come from the corporate stream.

What remains to be seen is how the municipal or residential collection of obsolete electronics will take shape over the next several years.

"The legislation in California to ban monitors from landfills is probably just a first step," predicts Strachan. "Within a few years, the federal government may have a general policy of not putting computers into landfills."

If this trend develops, it could eventually mean a bounty of obsolete electronic equipment destined for recycling plants such as Gold Circuit’s. "We’re going to get equipment from throughout the U.S., even the East Coast, because we can handle the volume," says Greenberg.

Collection events such as the one in the California town that collected 400 tons of electronic scrap could well become far more commonplace. It is unclear whether Gold Circuit will become more involved in the collection end, but the company is certainly ready to serve as a destination, and even has room to expand.

"We have designed the Casa Grande plant to put in a second processing line within six months if we need to," says Greenberg. "We feel the market is out there and ready, and that there is pent-up demand in California and beyond."

The author is editor of Recycling Today and can be contacted via e-mail at btaylor@RecyclingToday.com.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the September 2002 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta

- MTM Critical Metals secures supply agreement with Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations