Scrap recycling company owners and managers live in a workday world in which changes can occur suddenly or, conversely, in which a distressed market can linger far longer than what is tolerated in many other sectors.

Industry veterans, thus, are not greatly surprised when prices drop sharply and stay low for an extended period, and likewise they have seen previous stretches where material generation goes into an extended slump.

The ability for a company to survive an extended downturn takes not just experience and knowledge, industry veterans say, but also discipline and foresight.

An entire management book could be written based on the accumulated knowledge possessed by recyclers who have weathered three or more market downturns of the sort that have put some of their competitors into receivership.

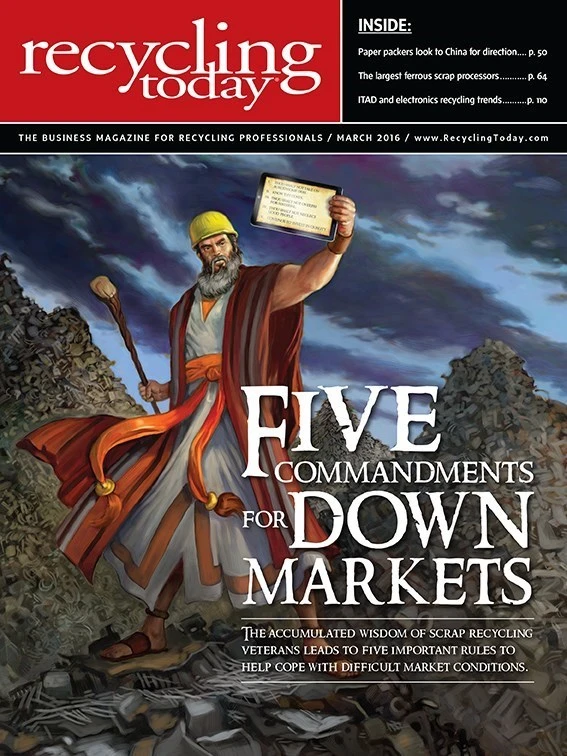

For the purpose of trying to distill some of that same knowledge into a format that can fit into a magazine article, what follows are five rules or commandments that fit within any lengthier volume offering advice on how scrap recyclers can manage through turbulent times.

By no means do these five commandments (or, if you prefer, strong recommendations) tell recyclers everything they need to know about how to survive a downturn. However, based on the common threads that emerged in talking to recycling industry veterans, they offer a good place to start.

i. thou shalt not take on burdensome debt.

Business loans and good banking relationships are as integral to the scrap business as to any other industry or service sector. What scrap recyclers seem to overwhelmingly agree on, however, is that the volatile revenue stream inherent to recycling means that debt-to-equity ratios that might be acceptable in other sectors can be a recipe for insolvency in the scrap business.

“Historically, it has proven to be true that lulls in business are great times to make changes: equipmentwise, efficiencywise and even just a change in business direction.” – Keith Highiet, Modesto Junk Co.

When scrap prices plunge and scrap volumes diminish, the monthly revenue for a scrap firm changes dramatically.

Recycling company owners may not agree precisely on when it is suitable to take out a loan or how much debt is too much, but they are nearly unanimous on the idea that there is a line that should not be crossed.

Overall, for a business to achieve a certain scale, “debt is not avoidable,” says Kevin Gershowitz, a principal owner of Gershow Recycling, Medford, New York. “But many times, industry members don’t manage debt well,” he continues. “While too much debt is never a good idea [in any business sector], in a commodity business and in a weak market, too much debt is a death knell.”

Melvin Lipsitz of M. Lipsitz & Co. Ltd., Waco, Texas, offers a blunt assessment: “Debt is a bad thing anytime. Typically, the interest you pay on debt and the typical net margin of profit for this industry [mean] the cost of money, even at low interest rates, can dissolve profits.”

Nonferrous scrap recycler Mark Lewon of Utah Metal Works, Salt Lake City, says that among the many scrap firms that purchased auto shredders during the (largely) bull market from 2003 to 2013, those who financed their purchases likely have learned a hard lesson.

Lewon, who also currently serves as chair-elect of the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI), Washington, states, “The buildup in shredders was fueled by debt. Now few, if any, shredders get enough material to run more than a couple of days per week. If that amount of volume isn’t enough to cover the payments, there is going to be a problem.”

Industry veteran Albert Cozzi, currently a principal with Bellwood, Illinois-based Cozzi Recycling, expresses a cynical view toward lenders, commenting, “Banks will always lend you whatever you want, as long as you don’t need it.”

The distressing corollary to that, he says, is that “in this environment,” when recyclers may benefit from a loan to supplement slumping revenue, banks “are just not lending to commodity-related businesses.”

Lewon says, “Debt is a tool, but it is a dangerous tool in that if the calculations for servicing that debt are inaccurate, and if volumes or margins fall short, disaster ensues.

“The bottom line is that the less debt a company has going into difficult economic times, the better the chances of its survival,” he adds.

ii. know thy costs.

Making a concerted effort to understand where outbound dollars are going and whether they are being spent wisely is an endeavor that proves worthwhile far beyond the scrap recycling industry. This knowledge proves particularly critical in a scrap industry downturn, however, when it comes time to react quickly to new market dynamics.

Sources cite careful recordkeeping and industry experience as factors that help savvier operators fully understand how and where money is being spent. “Those operators or entities who have been through prior low cycles understand the basic rule of ‘know your costs,’ managing your costs and keeping your costs low,” Kevin Gershowitz says. “This rule also allows for greater profits during better markets. The experience factor is very important.”

Steven Safran, president of Chicago-based wire processing firm Safran Metals, advises, “You should be running the business the same in the good times and the bad times, not just waiting for the bad times to ask, ‘Oh, where can I cut my costs?’”

Kevin Gershowitz expresses the same thought, saying, “The only way to survive the wake-up call [of a tough market] is to eliminate waste and fat. In good markets, efficiency can wane and costs rise. It’s easy to keep paying. However, in bad markets, those players that consciously choose to survive deliberately review their costs, efficiencies and spending.”

Cozzi offers a similar perspective, saying, “I am a big believer that operationally, when things are good, you run things as if things were going to get bad. That way, when things do turn bad, you don’t have to make many operational changes.”

The hard work is in the details, Cozzi adds, remarking, “It is important to look at every line item on the income statement regularly to see where costs can be reduced. Also, it is important to look at every item on the balance sheet to see where cash can be squeezed out.”

“The less debt a company has going into difficult economic times, the better the chances of its survival.” – Mark Lewon, Utah Metal Works

When a downturn hits, “Yes, you may have to change to adjust to volumes,” he says, “but whether things are good or bad, you have to look at your business every day and find ways to be more efficient and continually improve operations.”

John Tiziani, chief financial officer of Gershow Recycling, sums up this management principle by stating, “The companies that know every detail to their businesses survive in low markets and thrive in high markets.”

iii. thou shalt not overpay for material.

The adage “Scrap is bought, not sold” is one of the first phrases someone new to the industry learns, and the importance of the phrase is magnified when scrap buyers are operating in a declining or depressed market.

In bad times or good, prices paid for inbound material are likely the biggest numbers on the expenses side of the ledger, so avoiding overpaying is directly related to the “Know thy costs” commandment.

What veteran recyclers observe, however, is that overpaying can cause even more harm to a company’s balance sheet during bad times, and yet some company managers have a greater tendency to make this mistake in a market slump as they try to meet volume projections.

“Warren Buffet says, ‘You cannot buy market share; you can only rent it for a short period,” Cozzi says. He says the purchase of any grade from any supplier should be scrutinized as to whether it is contributing to profitability.

“Most scrap companies are looking at average cost of their purchases rather than incremental cost or marginal cost of both their feedstock and their operating expenses,” Cozzi says. “During good or bad times, the most important financial metric is contribution margin. Very often those marginal tons are providing negative contribution margin.”

Cozzi, who helped run Chicago-based Cozzi Iron & Metal before that family business was sold to Metal Management Inc. (now Sims Metal Management) in 1998, says maximizing volume may keep machinery active, but that does not necessarily make it the right approach.

“Whether our family ran one or 40 yards, we always did a sensitivity analysis for each yard to make assumptions [about] what price would provide what tonnage, and at what levels is contribution margin maximized. Generally, that answer is at a lower tonnage and lower price point.”

Safran says his family company has remained a modestly sized business in part because it follows this same logic, even during boom markets. “This is the reason Safran Metals has been lean over the years: If we’re looking to pick up new business, we want to pick up business that makes sense. We’re not just looking to pick up marginal business. And I’m guessing too many dealers pick up marginal business, and especially business where you also have to increase your overhead. If so, then you’re putting yourself in more of a risk situation.”

Elliott Gershowitz, a co-principal at Gershow Recycling, along with his brother Kevin, comments, “Don’t overpay for market share on the basis of more volume. You can make the same profit if not more sometimes just by widening your spread and working on lower volumes.”

Kevin Gershowitz elaborates, saying, “Overpaying for raw material is a contagious, infectious disease. The old adage of ‘Make it up in volume’ is just as false today as it was then.” He concludes, “One has to be smart when buying. One needs smart buyers when buying. Anyone can buy if they overpay.”

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

Sponsored Content

Labor that Works

With 25 years of experience, Leadpoint delivers cost-effective workforce solutions tailored to your needs. We handle the recruiting, hiring, training, and onboarding to deliver stable, productive, and safety-focused teams. Our commitment to safety and quality ensures peace of mind with a reliable workforce that helps you achieve your goals.

iv. thou shalt not neglect good people.

When a downturn hits and then lingers, it becomes exceedingly difficult for a company manager to avoid painful personnel decisions. The negative impacts are clear to the employees being laid off or terminated and can be nearly as traumatic for the managers who have to make and communicate these decisions to their employees.

More subtle but of great importance in the long term is the risk to a company’s future when employees who are critical to the workplace knowledge base, culture, morale and future productivity gains of a company are among those who are terminated or leave the company after a payroll cut.

When asked about cost cuts to avoid during difficult times, Keith Highiet of Modesto Junk Co., Modesto, California, says, “Neglecting equipment or losing good people are not options. There are other expenses that can be cut first.”

A recycling company that wishes to retain its key employees through a downturn may need to turn to reduced hours as a cost-cutting technique. “Reduced hours and having good supervision are the keys,” Lipsitz says.

Safran says, “I have never laid anybody off [because of business conditions], maybe because we’ve been lean and mean. The workers help me make money in the good times, and I look at it that I have to take care of them in the bad times. We may need to cut back on hours, but if you have good people, and you spend money training them, you look at what you have to do to keep key employees.”

Lewon says good communication prevents workers from either being blindsided by bad news or from failing to understand the seriousness of a market downturn. “Explain to your people exactly what is going on so that they are aware,” he comments.

Even with the best management practices, “I think that choices have to be made,” Lewon says, when it comes to adjusting personnel levels to meet market realities. “Don’t be afraid to let marginal employees go. Tell the good employees that you want to keep them and that you will work with them to help them make it.”

v. continue to invest in quality.

When scrap prices are low and volumes have slowed to a trickle, it is likely that cash flow conditions will be on the tight side of the spectrum as well. A combination of tight cash flow and a commitment to avoid burdensome debt would seem to make a downturn an unlikely time to invest in operations improvements. However, veteran recyclers warn that neglecting one’s equipment for any consi

derable amount of time is likely to yield negative results. Retaining a high level of quality in operations starts with equipment maintenance, recyclers seemed to unanimously agree. (See the sidebar “Always Maintain”)

Beyond that important rule, veteran recyclers also say a market slump can provide managers with available time to research new equipment, adding that they often encounter equipment makers eager to make a sale during a lull.

“Historically, it has proven to be true that lulls in business are great times to make changes: equipmentwise, efficiencywise and even just a change in business direction,” says Highiet.

“Often, equipment salespeople are willing to deal in order to make sales in tough times,” Lewon says. “For anyone with cash and a long-term view, sometimes difficult times can be a great time to buy equipment.”

Kevin Gershowitz, who has encountered the same circumstance, says, “Better deals can be had on certain equipment from those sellers in need of making sales.”

Yet more critical than saving a few dollars, he says, is preparing to be competitive in the long run. “More important than the savings on the investment is the ability to be ready to go when the markets recover,” he states.

Kevin Gershowitz also points to the importance of keeping in mind the extended research, purchase and installation timeline for such a project.

“The workers help me make money in the good times, and I look at it that I have to take care of them in the bad times.” – Steven Safran, Safran Metals

“On some scrap processing equipment, from investigation to contract to install, it can take over a year for new processing equipment to become operational. Installing now and being in the game when the market recovers is better than beginning to install when the market recovers and then begin operating when the market tanks again,” he comments.

The first quarter of 2016 has provided financial press headlines pertaining in particular to China’s economy and the woes of the global steel industry that may well help to prolong the difficulties in the commodities sector.

Recycling industry veterans are far from complacent, but they do profess a certain amount of faith that abiding by time-tested management principles will help make the slump bearable.

“This downturn is having real consequences,” Highiet says. However, he adds, “The ability and wherewithal to weather prior [slumps], from controlling costs to accepting smaller profit margins with reduced flows of scrap, are helpful to rely upon in the current environment.”

Kevin Gershowitz says, “The fixed costs of operating a scrap yard are real and very expensive. The percent of gross margin needed to cover costs increases as market pricing lowers. When pricing is high, margins are wide and just about any company or individual can generate profits. Low pricing is a different business skill set. As market pricing lowers, margins get squeezed and do not expand. This explains many of the closures we read about.”

Cozzi returns to the idea of veteran leadership as making a difference for some scrap companies. “I believe that people in the industry prior to 2000 do have an advantage over people who are more recent to the business. They have lived through the cycles of the commodities market and of the economy,” he states.

Whether the rest of 2016 brings with it low prices or rising prices, employees of scrap companies with veteran leaders are likely to hear from them with variations of these five commandments and other lessons learned from previous experience.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the March 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Green Cubes unveils forklift battery line

- Rebar association points to trade turmoil

- LumiCup offers single-use plastic alternative

- European project yields recycled-content ABS

- ICM to host colocated events in Shanghai

- Astera runs into NIMBY concerns in Colorado

- ReMA opposes European efforts seeking export restrictions for recyclables

- Fresh Perspective: Raj Bagaria