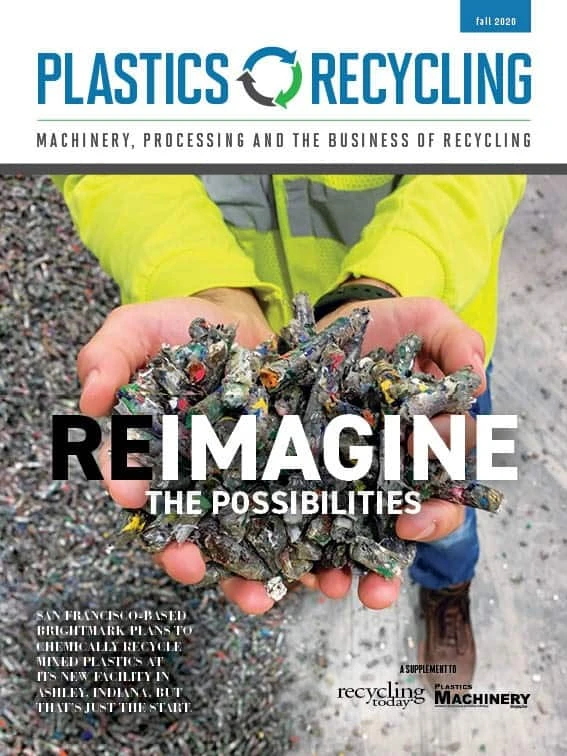

Photo courtesy of Brightmark

Earlier this year, San Francisco-based Brightmark Energy changed its name to Brightmark to better reflect the overall scope of the company, which, CEO Bob Powell said at that time, is to “change the world” in part by globally scaling its plastics renewal technology to chemically recycle plastics Nos. 1-7.

“Our team shares the imagination, grit and optimism that is driving this company to globally scale solutions to our most pressing environmental challenges,” he said.

Redefining waste

A group of engineers formed Brightmark in 2016 with the goal of developing innovations to benefit the environment. The company says it uses “science-first” approaches and partnerships to transform organic waste into renewable natural gas and to create innovative approaches to managing end-of-life plastics.

Powell, co-founder of Brightmark, has spent most of his career working in the renewable energy industry, including as president of North America for SunEdison, president and CEO of Solar Power Partners and chief financial officer for Pacific Gas & Electric. Zeina El-Azzi, co-founder and chief development officer at Brightmark, has spent nearly 20 years in the power and energy fields, focusing on renewable energy.

Powell says the company is “hoping to reimagine waste by creating a world without waste.” Brightmark is developing what he describes as “holistic solutions that are closed-loop and tackle the most pressing environmental challenges.”

Since the business partners founded Brightmark, the company has added to its staff; accumulated $150 million in equity investments in its projects; and acquired RES Polyflow, formerly of Chagrin Falls, Ohio, and its chemical recycling technology for mixed plastics. That technology is a key part of Brightmark’s $260 million “plastics renewal facility” in Ashley, Indiana, that plans to recycle 100,000 tons of mixed plastics annually into ultra-low-sulfur diesel, naphtha and wax.

Jay Schabel is president of Brightmark’s Plastics Division. He founded RES Polyflow, where he served as CEO before Brightmark acquired the company. At Brightmark, Schabel is responsible for the development and integration of the business and the establishment of commercial operations in Indiana.

“I spent the last 12 years working with the technology we are employing” to chemically recycle plastics, he says.

RES Polyflow connected with Brightmark in 2018 when RES Polyflow was looking for equity partners to help fund its Indiana facility.

Beyond its Plastics Division, Brightmark has partnered with 20 dairy farms in six states to produce renewable natural gas using anaerobic digestion technology. The company says these projects have the potential to generate enough renewable natural gas annually to drive more than 5,000 18-wheelers from San Francisco to New York City.

Addressing end-of-life plastics

Brightmark plans to expand its Plastics Division nationally and globally. Domestically, it has been looking at Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas as possible sites for future plastics renewal plants.

Globally, Brightmark is focusing on Europe and Asia, Powell says. The firm has targeted Europe because its waste and recycling infrastructure is “more robust.” However, it has targeted Asia for the opposite reason.

“The most important reason we’ve targeted Asia is because waste management and the volume of waste is an issue,” he says. “[Nongovernmental organizations] like the Alliance to End Plastic Waste in Singapore are looking for folks like us to solve this issue with technology.”

Powell is referring to the nonprofit organization funded by nearly 50 companies across the plastics value chain. The funders behind the Alliance to End Plastic Waste have committed $1.5 billion to develop solutions designed to prevent the leakage of plastic waste into the environment and to recover and create value from this material.

Brightmark says it plans to have two additional sites ready to build in the U.S. by 2021. The company plans to announce those sites shortly, but it had not made that information public as of Oct. 2. It plans to invest $500 million to $1 billion at each U.S. site, which will process hundreds of thousands of tons of plastics annually.

With its new sites, Brightmark is seeking local, regional and state support for project development through incentives and improved plastic recycling programs; access to at least 200,000 tons of commingled plastic scrap annually; access to 30 to 100 acres of suitable land with access to rail and highways; and natural gas and electric utility support, according to the company.

Powell says not only is having access to large amounts of plastics important for these future locations, but so is access to end markets.

The company’s Indiana site, for example, is near London-based BP’s largest refinery in the Chicagoland area. That company has signed an offtake agreement with Brightmark to purchase the fuels produced by the facility. (See the sidebar below for more information on the companies’ partnership.)

Schabel says feedstock for the Indiana facility will be sourced from within a 170-mile radius that includes that state as well as from Ohio and the Chicago metro area.

Powell says most of Brightmark’s feedstock will come from material recovery facilities (MRFs), but it also is targeting manufacturers of products as varied as car seats and cosmetics. “We found that there are a lot of folks with sustainability goals that would very much like to direct products to our process,” he adds.

More broadly, Brightmark is working to procure more than 1.2 million tons of plastic scrap from the eastern half of the U.S. for recycling at its Indiana location and its planned plastics renewal plants nationwide.

The Indiana site is in the testing phase with plans to be at production scale early next year, Powell says.

Brightmark also is considering a hub and spoke model, he says, where preprocessing facilities could be sited in more remote areas to debale, shred and pelletize incoming plastics. These pellets could then be loaded into rail cars and transported more efficiently for additional processing at the company’s plastics renewal facilities, Powell explains. He adds that Brightmark’s goal is to collect postuse plastics from communities in the most sustainable way possible.

The technology

“Brightmark was attracted to the flexibility of the technology” RES Polyflow had developed, Schabel says.

Powell says the technology is unique in that polyvinyl chloride (PVC) can represent 8 to 9 percent of the total composition of the mixed plastics feedstock. “Our advantage is that it is cost-efficient and that we can take and prefer to take a mixed plastics stream,” he says. “Other technology in chemical recycling can only take a single stream. That doesn’t solve the problem; you need to take the full array that we throw away.”

Schabel says PVC is 30 to 50 percent chlorine, which Brightmark can remove before or after processing, depending on what is most economical.Brightmark employs a form of pyrolysis, Powell says. First, the mixed plastics are debaled and sorted to remove nonplastics. The plant employs optical and magnetic sorting technology, with Schabel adding that items that are not attractive to the company potentially can be reused or recycled in a different manner.

The mixed plastics are then shredded, dried and pelletized. The resulting pellets are placed in heated stainless steel vessels, known as plastic conversion units (PCUs), that measure 8 feet in diameter and 60 feet long, Powell says. The vapor produced in the heating process is captured and cooled, creating fuels and the building blocks for future plastic products.

Powell says the Indiana plant will produce ultra-low-sulfur diesel and naphtha that will be supplied to BP. The naphtha the plant produces can be blended into gasoline or even used to make new plastics. The waxes generated in the process will be marketed by Am Wax, headquartered in La Mirada, California. Am Wax is an international trading company that specializes in paraffin waxes for a wide variety of applications and cascade wax for the corrugation industry.

In Ashley, the company will consume 100,000 tons of plastic per year and will create 18 million gallons of diesel or naphtha and 6 million gallons of wax.

Schabel says Brightmark’s Plastics Division has the goal of processing 1 million tons of mixed plastics per year by 2025, which is 10 times the production of the Indiana plant. That facility will have 32 PCUs on-site as well as downstream refining equipment. However, he says future facilities, particularly those overseas, could have as few as two PCUs, though most will have from 16 to 32 PCUs.

He says he sees the opportunity to partner with downstream customers for offtake agreements or upstream generators, such as municipalities, at the company’s future sites. Brightmark takes RUFUS, its remote universal feedstock utilization system, to potential suppliers to evaluate their material streams.

While some material recovery facilities have discontinued producing mixed plastic bales following China’s ban on imports of postconsumer plastic scrap, Schabel says he is not worried about securing feedstock for Brightmark’s planned facilities. “Once we have proven the chemical recycling process, we anticipate seeing a shift in the recycling and waste industry to bring in those products,” he says.

Addressing its critics

Schabel says much of the media attention on plastics has been associated with the evils of end of life. However, he says it’s important not to “throw out a material that is a good material because it has no end-of-life solution” but to create an end-of-life solution.

Powell says Brightmark is looking to create solutions that are “as pragmatic and circular as possible.”

To the critics who say that producing fuels is not truly recycling, Schabel says it is difficult to get to “utopia in one step.” While Brightmark can produce the precursors to make plastics, the assets needed to produce new plastics may not be available in every location, though plastic scrap is, so having flexible end products is important. “It can adapt to every environment and other places in world.”

Powell adds that the fuels the company will produce still eliminate virgin production and the associated methane released during extraction.

“We are on a journey: fuels today, plastics tomorrow,” Schabel says. “Brightmark’s view is that we are not going to reach perfection tomorrow, but we are going to make the world a better place.

“Wherever the plastic waste is being generated is where we need to be,” he continues. “We will place a value on plastic and divert it from the waste stream, and it can be a source of energy or virgin raw materials.”

Explore the Fall 2020 Plastics Recycling Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Orion ramping up Rocky Mountain Steel rail line

- Proposed bill would provide ‘regulatory clarity’ for chemical recycling

- Alberta Ag-Plastic pilot program continues, expands with renewed funding

- ReMA urges open intra-North American scrap trade

- Axium awarded by regional organization

- Update: China to introduce steel export quotas

- Thyssenkrupp idles capacity in Europe

- Phoenix Technologies closes Ohio rPET facility