Residential recycling programs have been in place in most cities and towns in the United States for the better part of the last 30 years. While commodity markets have had numerous ups and downs, recycling generally has made good sense environmentally and economically for everyone involved.

Until recently, haulers, whether municipalities or private companies, would collect materials and take them to be processed at material recovery facilities (MRFs), and MRF operators would pay the collection companies for each ton of material they delivered to the facility. In good times, collection companies could receive upwards of $25 per ton for the recyclables they delivered. The earnings from these recyclables helped subsidize the cost of providing the collection service to residential customers, who expected recycling to be “free” or at least less expensive than trash collection.

Now, we have gotten to the point where recycling veterans are saying, “Recycling as we know it isn’t working.” (This was James Warner, chief executive of the Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Solid Waste Management Authority, in the Wall Street Journal article titled “Recycling, Once Embraced by Businesses and Environmentalists, Now Under Siege,” from May 13, 2018.)

How did we get here?

Changing dynamics

Residential recycling will not make economic sense in many places in the U.S. unless customers pay more for the service. The current price that haulers charge to collect recyclables from homes does not come close to covering the costs of deploying a truck and driver and delivering recyclables to a MRF. MRF operators are now charging haulers upward of $30 per ton to process recyclables when they paid them for this material in the past.

While there are numerous explanations for the situation recycling finds itself in today, two related drivers are clearly among the most important: 1) high levels of contamination in the recyclables collected from homes and businesses; and 2) changing international markets, especially in China, for recyclable commodities.

Addressing contamination

What do we mean by contamination?

When residential recycling customers put out their bins full of old newspapers, cardboard boxes, junk mail, water bottles, aluminum cans and milk jugs, they face a dilemma: Should I put this item in the trash or in the recycling bin?

When recycling bins were small, people put objects that may or may not be recyclable in the trash. However, when customers were given large rolling carts for recyclables, they defaulted to putting the object in question in the recycling container (a practice known as “wishcycling”). Many items have come across MRF conveyor systems that have no business being there: strings of Christmas lights, dirty diapers, bowling balls, car mufflers, dirty pizza boxes, etc.

In some cities, contamination levels of more than 30 percent are the norm. Even in “good” cities, contamination is frequently in the 15 to 20 percent range.

The MRF tries to get all this contamination out of the finished commodities, but success is limited. Bales of processed cardboard typically contain at least 5 percent contaminants by weight (92.5 pounds of junk for every 1,850-pound bale of material). To reduce contamination levels, conveyors must be slowed down and additional sorters (either people or devices) need to be added—both of which make processing costs higher than they were previously.

Assessing China’s role

For more than a decade, Chinese paper mills have been important buyers of recovered paper from the U.S. Last year, the Chinese bought almost two-thirds of the recovered paper and half the scrap aluminum the U.S. sold overseas, according the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI), Washington. For years, Chinese mills complained about the recovered paper’s quality, but they continued to buy it, and we continued to sell it to them.

Things have changed now, and they are unlikely to ever go back to the way they were. The Chinese government has responded to concerns that China had become the dumping ground for other countries’ trash. Pollution levels in China are high, and air and water quality is poor. In early 2018, the Chinese government imposed a restriction of no more than 0.5 percent contamination in recovered paper sold to China. (This amounts to 9 pounds of junk in a 1,850-pound bale.)

Without the Chinese market to sell to, U.S. recyclers have turned to other markets in Asia and to domestic producers, but recovered paper has flooded those markets, and prices have come crashing down. The price for 1 ton of mixed paper—a hybrid of small cardboard, newspaper, magazines and cereal boxes that sold for $50 per ton one year ago—has a value of less than $0 in many parts of the U.S. today.

No one in the recycling industry believes these challenging market conditions reflect normal commodity cycles; this time it is different. The importation of recyclables has become a political cause in China, not just an economic one. And trade tensions between the U.S. and China are not helping matters, as recent disputes resulted in a 25 percent tariff on recyclables imported into China from the U.S.

Helping to bear the cost

What does this mean to customers of recycling services?

In the short term, they will have to pay more of the cost of recycling.

Recycling has not become less profitable to collection companies and MRF operators; in many cases it has become unprofitable. MRF operators who face rising costs and falling values for their commodities are passing costs on to collection companies, and collection companies will pass those costs on to customers.

Sooner or later, every hauler will be forced to pass on these costs. Some may charge more for trash service to continue the illusion that recycling is significantly less costly than trash collection, while others will charge more for recycling services and try to explain what is happening in the recycling business.

No one is happy about the situation, but recycling that does not make economic sense is just not sustainable.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

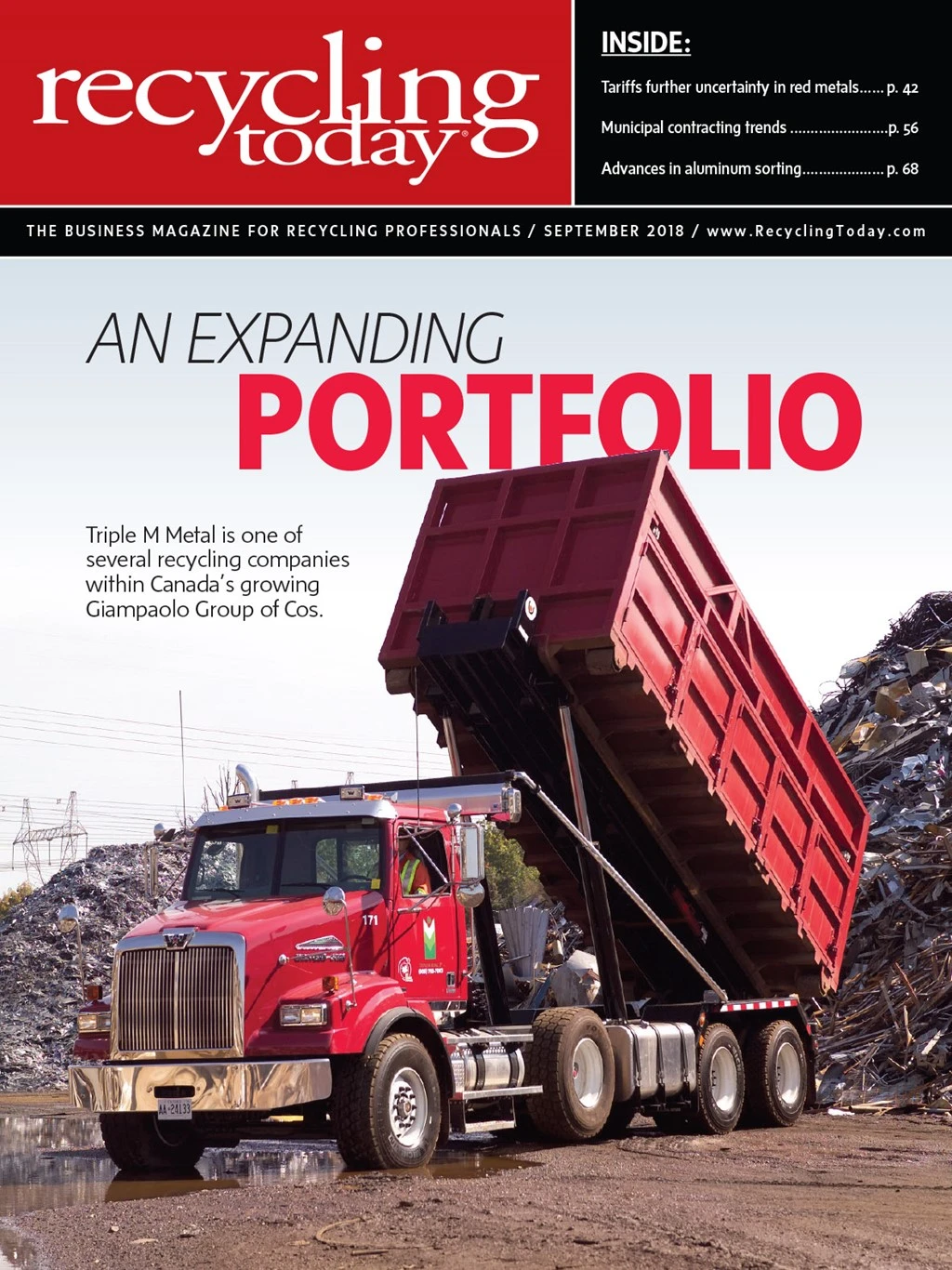

Explore the September 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- ReMA board to consider changes to residential dual-, single-stream MRF specifications

- Trump’s ‘liberation day’ results in retaliatory tariffs

- Commentary: Waste, CPG industries must lean into data to make sustainable packaging a reality

- DPI acquires Concept Plastics Co.

- Stadler develops second Republic Services Polymer Center

- Japanese scrap can feed its EAF sector, study finds

- IRG cancels plans for Pennsylvania PRF

- WIH Resource Group celebrates 20th anniversary