Balers, traditionally found in material recovery facilities (MRFs) that process a variety of recyclables, create compact cubes of material to help maximize

“Installing a baler certainly requires more labor, but when you manage the dollar value you get on it, it grossly outweighs the costs of labor by a long shot,” Kevin Herb, managing partner of Broad Run Construction Waste Recycling in Manassas, Virginia, says. “Why people aren’t baling in C&D—I don’t get it.”

Herb says baled material can be cleaner and, therefore, garner a higher value than loose recyclables.

Balers also densify material, increasing the volume of material that can be loaded into the trailers used to haul the material. This reduces the number of trips required to haul the same amount of material, reducing transportation costs.

“Any business person is in business to make money, and the return on investment (ROI) is something every decision-maker looks at and makes a decision on,” Herb says. “In this case, the return on investment is excellent.”

GETTING WHAT YOU PAID FOR

Broad Run accepts dirt, old corrugated containers (OCC), clean white dimensional lumber, aggregates and 5-gallon high-density polyethylene (HDPE) paint buckets for recycling. Of the more traditional commodities recovered from C&D material, the processed dirt serves as medium-grade topsoil and fill material, while the aggregates are sent to local concrete crushing plants. The baled OCC is shipped to

Broad Run has baled OCC since it opened in 2008 using a Model CE-504842-830 manual-tie, closed-end horizontal baler from Marathon Equipment, based in Vernon, Alabama. Since the baler’s installation, Broad Run has been producing seven OCC bales per day.

It wasn’t until February 2014 that Herb and his crew began recycling plastic paint buckets, installing a second manual-tie, closed-end horizontal baler: a Gemini Extreme model that also was manufactured by Marathon.

“We were just throwing them away,” Herb says of the buckets. He adds that the existing pickers were asked to start targeting these items as well, so no extra labor was needed to pull the buckets out from the waste stream.

Because the company already had an experienced operator for the baler on its paper line, there was no need to add and train an employee to operate the new baler.

Broad Run produces two bales of plastic buckets per day. Over the course of a month, the company’s pickers pull approximately 23 tons of buckets from the incoming material stream, Herb says, which when baled are enough for one tractor-trailer load.

It takes the baler operator roughly 13 minutes to remove an OCC bale from the baler, tie it and put it in the storage area. For the plastic buckets, the process takes 35 minutes.

“There’s more time involved because of the paint,” Herb says. Much of that extra time is spent cleaning up the paint that is released during the

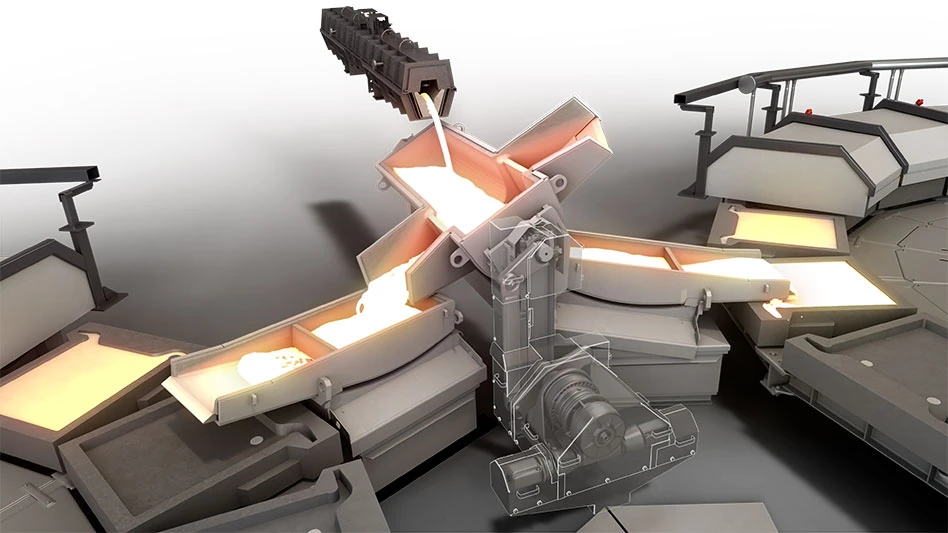

Herb says he decided to place the balers beneath the picking stations in his systems for efficiency. Employees pick items off the belt and drop them down a chute and into a baler.

Herb says the approach is less expensive than using a conveyor to transport the material into the hopper of the baler. “The cheapest way is letting gravity do the work.”

Installing the baler for the plastic line took around one day, Herb

The temporary expenses associated with the installation of the balers soon paid off, he says. It took Broad Run three months to see a return on its investment in the OCC baler it installed in 2008. Broad Run considered the decreased trucking expenses when evaluating its ROI.

“If it isn’t baled, it’s loose. And if you’re transporting it

“These bales are 1,600-to-1,800-pound cardboard bales—almost a ton a piece—so you can only imagine if that was loose in some kind of container or compactor.”

The bucket bales weigh in at 800 pounds each. The state of Virginia’s truck weight limit is 25 tons, so baling allows Broad Run to get the maximum weight on each truckload.

“You can get that maximum weight with

CUTTING its LOSSES

Recovery1 in Tacoma, Washington, used four balers at its Carpet Processing & Recycling LLC (CP&R) plant—a 100-horsepower Harris two-ram horizontal baler with an auto-tie system that it bought in 2007; a 15-horsepower Lummus horizontal closed-end manual-tie fiber baler; a 15-horsepower Walters vertical manual-tie fiber baler; and a 15-horsepower Max-Pak manual-tie vertical foam baler.

Recovery1 rented its first baler in 2000 to bale nylon-6 (N-6) face fiber carpet, which it sold to Evergreen Nylon Recycling in Augusta, Georgia.

However, Evergreen shut down in September 2001 because, according to Recovery1 General Manager Terry Gillis, the facility could only process N-6 carpet. However, over the years, that material decreased in popularity in favor of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fiber, which is manufactured from recycled bottles.

In 2003, Shaw Industries Group in Dalton, Georgia, purchased the Evergreen facility and reopened it. Recovery1 then began supplying the plant with baled N-6.

In 2007, Gillis says, Recovery1 began baling mixed plastic film and mixed rigid plastic for Asian markets and OCC for a local paper mill to recycle into

The Harris baler was purchased used from a nearby nonferrous recycling facility, where it processed aluminum. But, with the Recovery1 crew’s “technical expertise,” Gillis says, it was reconditioned to meet the company’s carpet processing needs.

“Employees at Recovery1 have built most of the equipment we use to process C&D, and much of what we have purchased from equipment manufacturers

Though the baler was “much larger” than needed, Gillis says, it was a good opportunity to expand Recovery1’s capabilities. The machine baled N-6 carpet, Nylon-6.6 pad, OCC, mixed plastic film, mixed rigid plastic, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe and PVC fencing and siding, he says

In 2011, Recovery1 bought the Walters baler to experiment with baling nylon fiber extracted from

In 2016, the company opened CP&R in Tacoma to focus on recycling carpeting and purchased the Lummus baler to capture face fiber extracted from

Later in 2016, the CP&R plant rented the Max-Pak baler to bale carpet pad.

Recovery1 shut down the CP&R plant in the summer of 2017, Gillis says, because the value of

The company is selling its Lummus and Walters balers and returned the Max-Pak baler to the rental firm.

While Broad Run Recycling has found success operating balers in its C&D recycling facility, Gillis is less optimistic about this application.

“Baling in a C&D plant gives the operator an opportunity to divert a portion of the materials coming in with commingled C&D debris into commodities that may have value in the marketplace. However, most of what is baled

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the February 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Recycling Today

- Unifi launches Repreve with Ciclo technology

- Fenix Parts acquires Assured Auto Parts

- PTR appoints new VP of independent hauler sales

- Updated: Grede to close Alabama foundry

- Leadpoint VP of recycling retires

- Study looks at potential impact of chemical recycling on global plastic pollution

- Foreign Pollution Fee Act addresses unfair trade practices of nonmarket economies

- GFL opens new MRF in Edmonton, Alberta